Gates of the Arctic National Park via Anaktuvuk Pass

Most people view Gates of the Arctic National Park, one of the finest and largest wilderness areas in the world, as a place expressly set up to be devoid of human presence. However, for millennia, native mountain Eskimo people have sustained a nomadic lifestyle revolving around the caribou migration on this land. Contact with modern life led the Nunamiut to settle Anaktuvuk Pass in 1949. The village is named after a broad mountain pass from which the Anaktuvuk River originates, and which is on the caribou migration route. With a current population of 300-400, it remains the only Nunamiut settlement in existence, which in itself makes it a worthwhile destination.

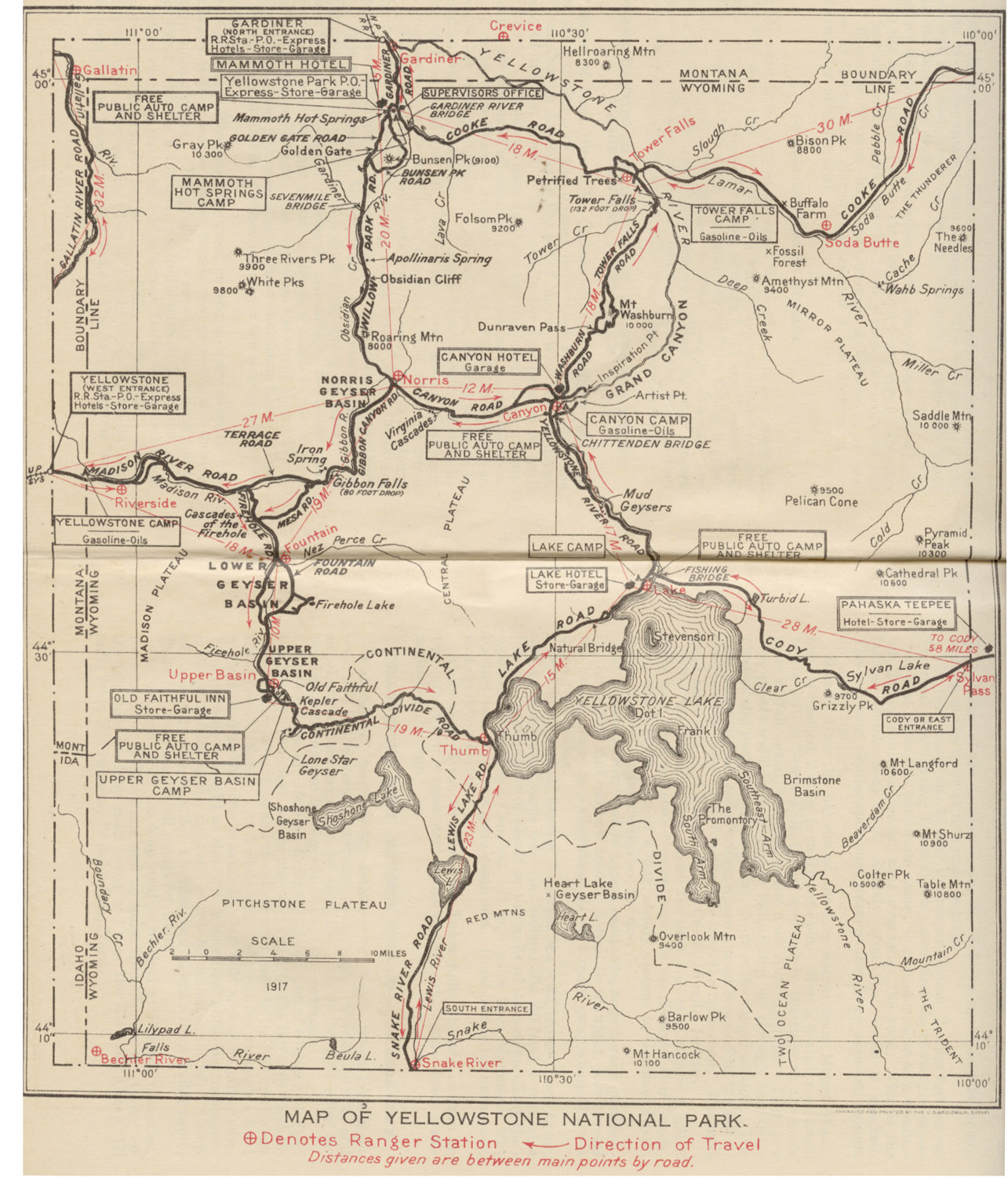

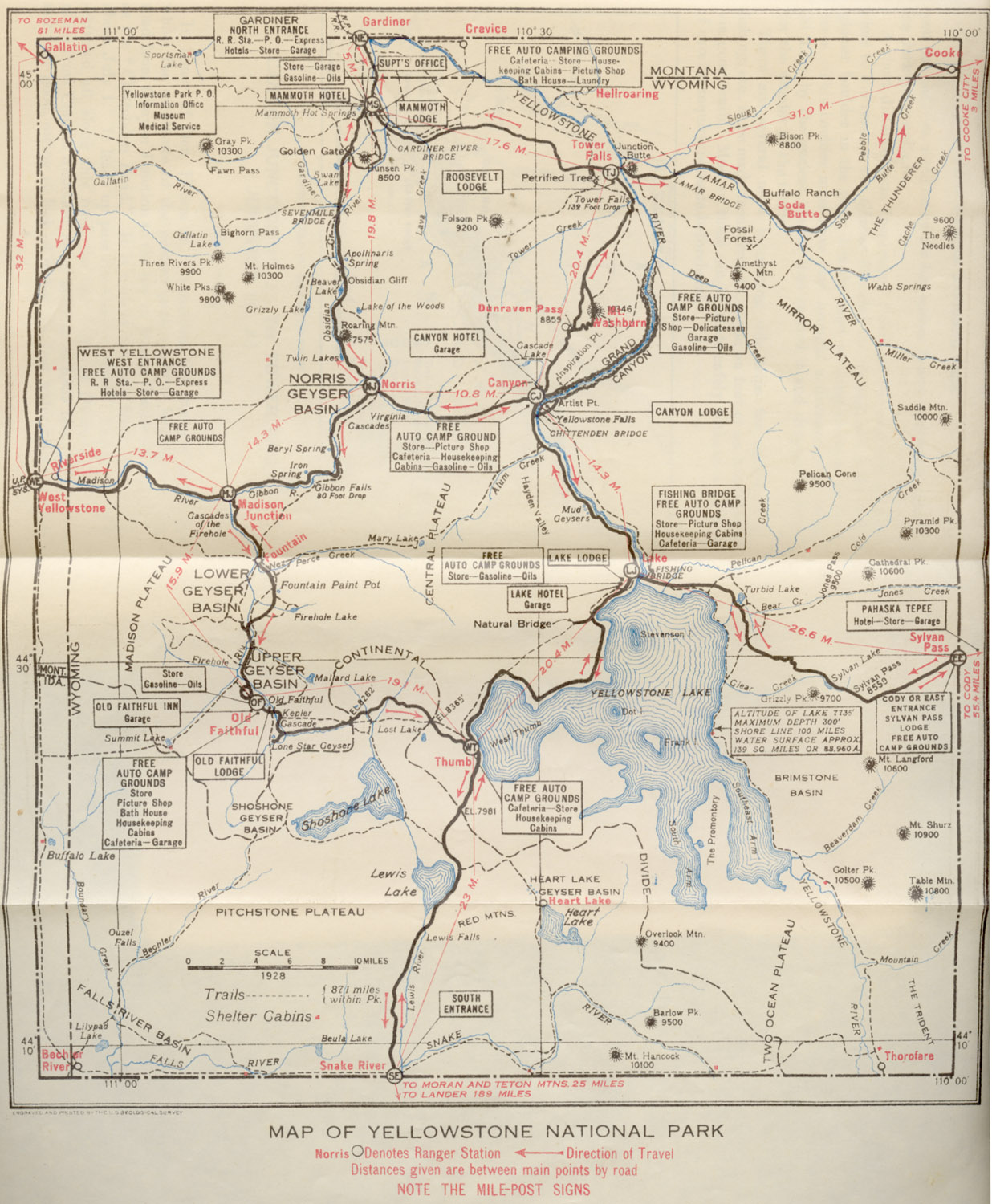

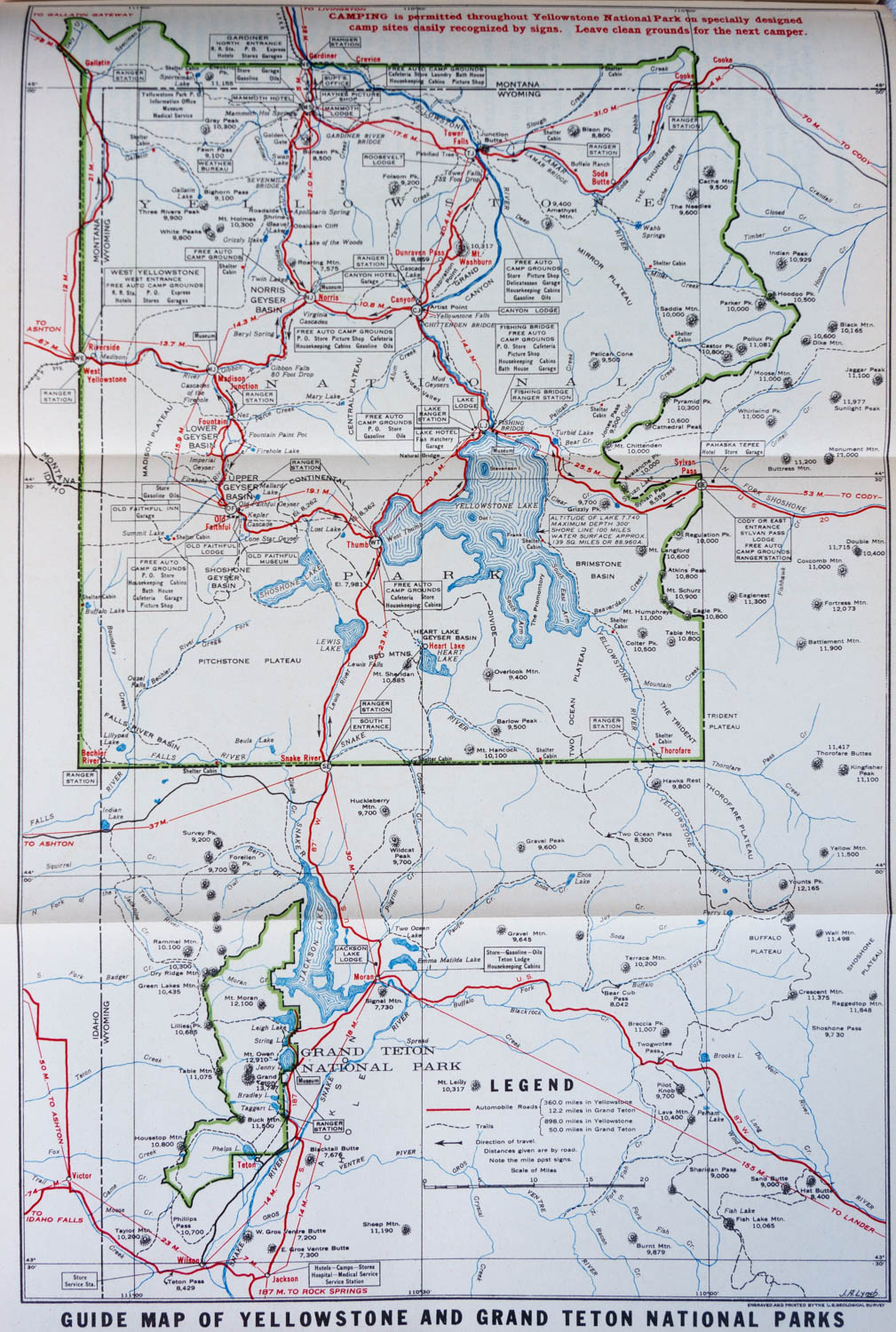

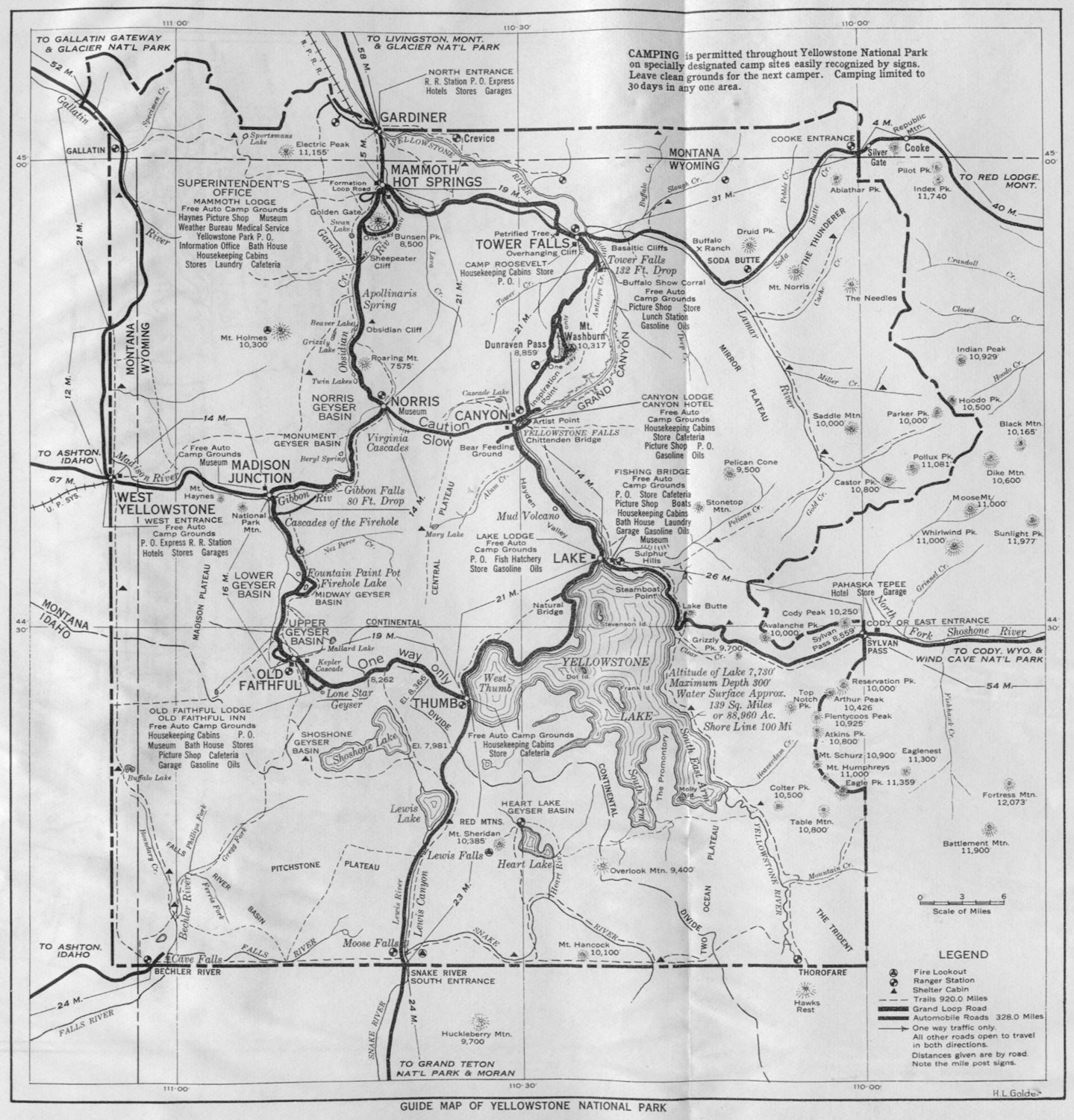

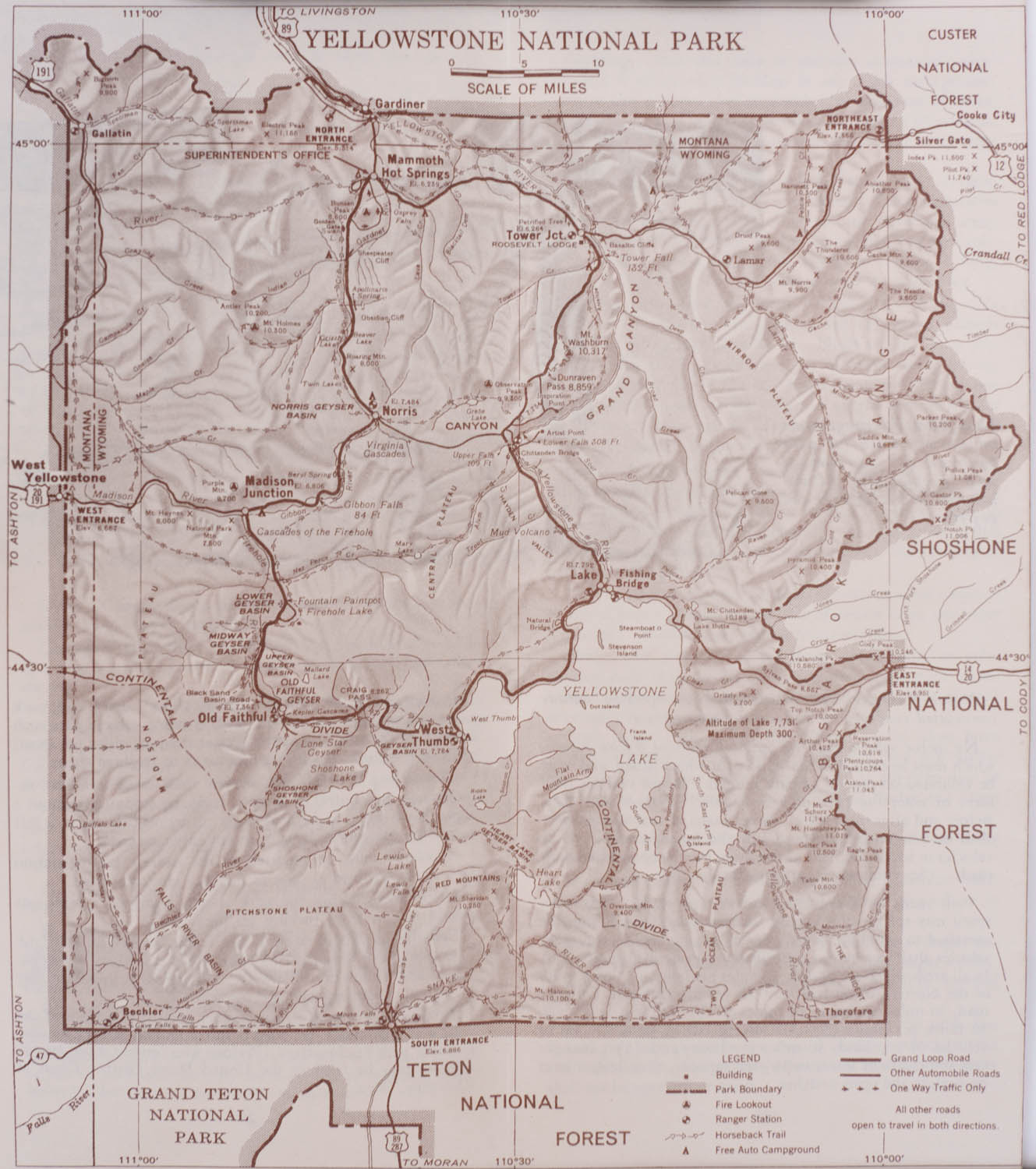

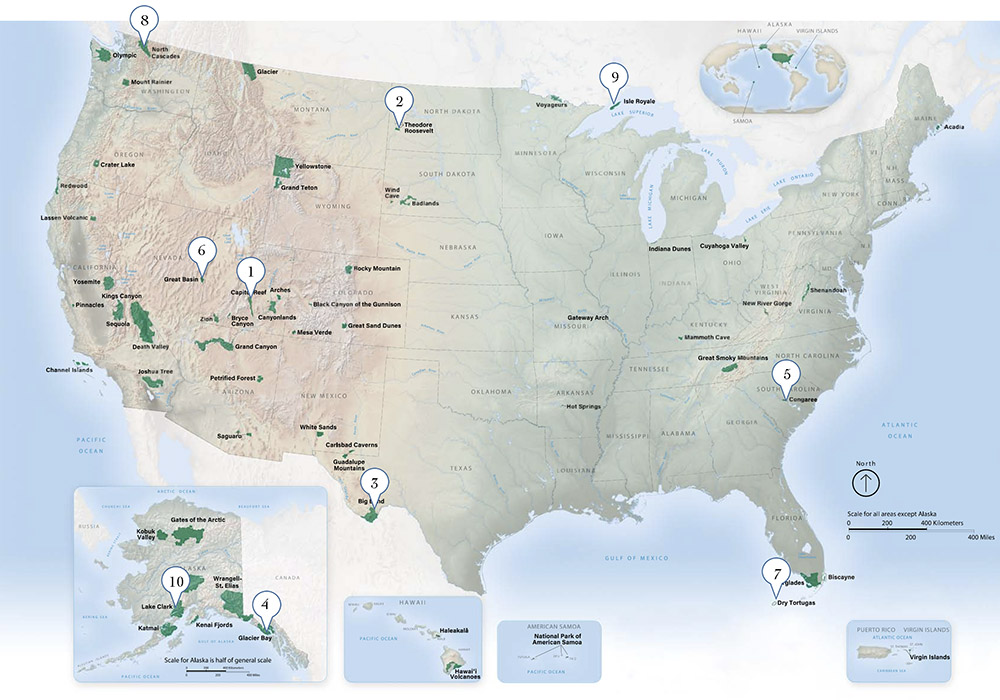

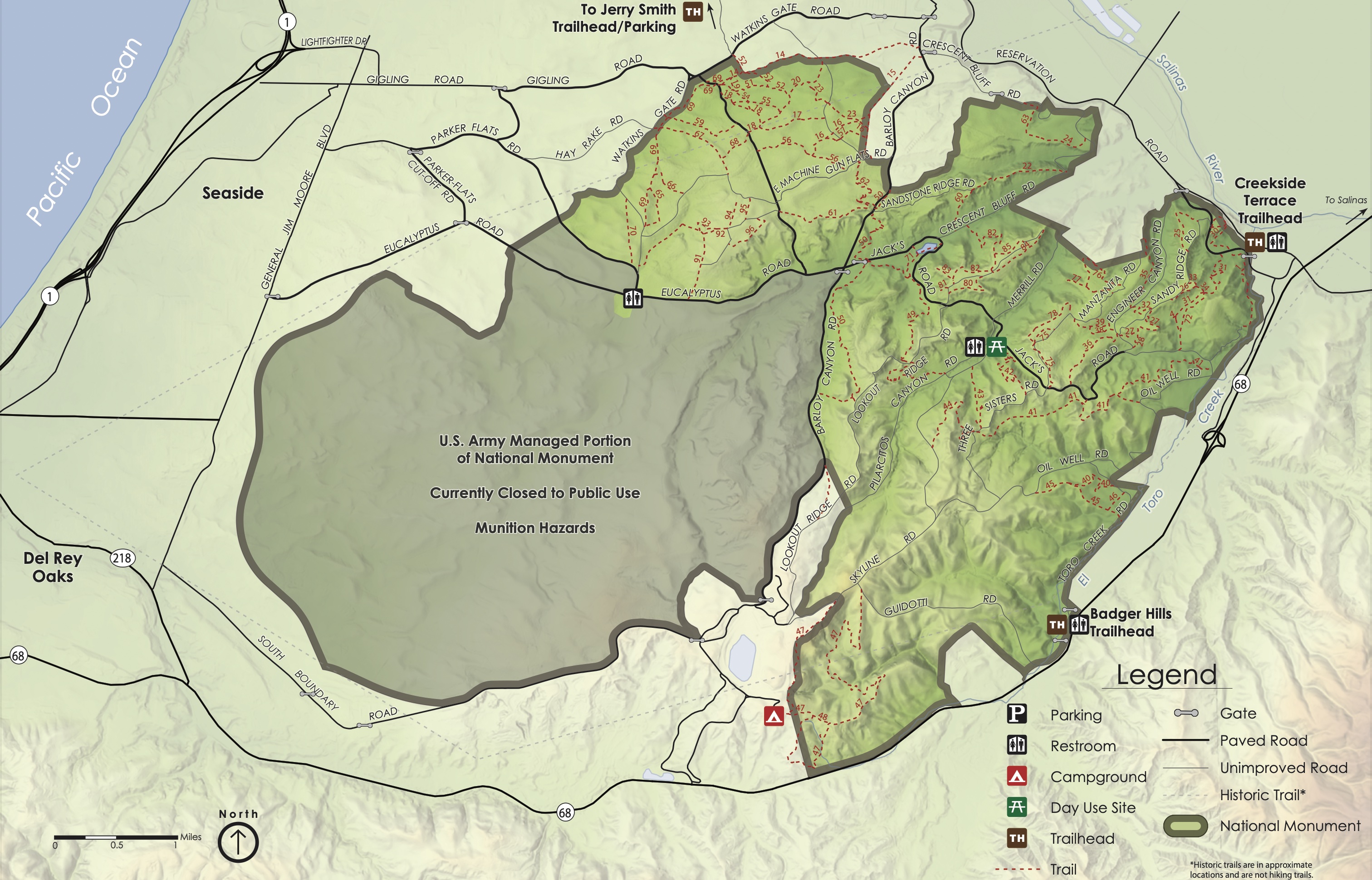

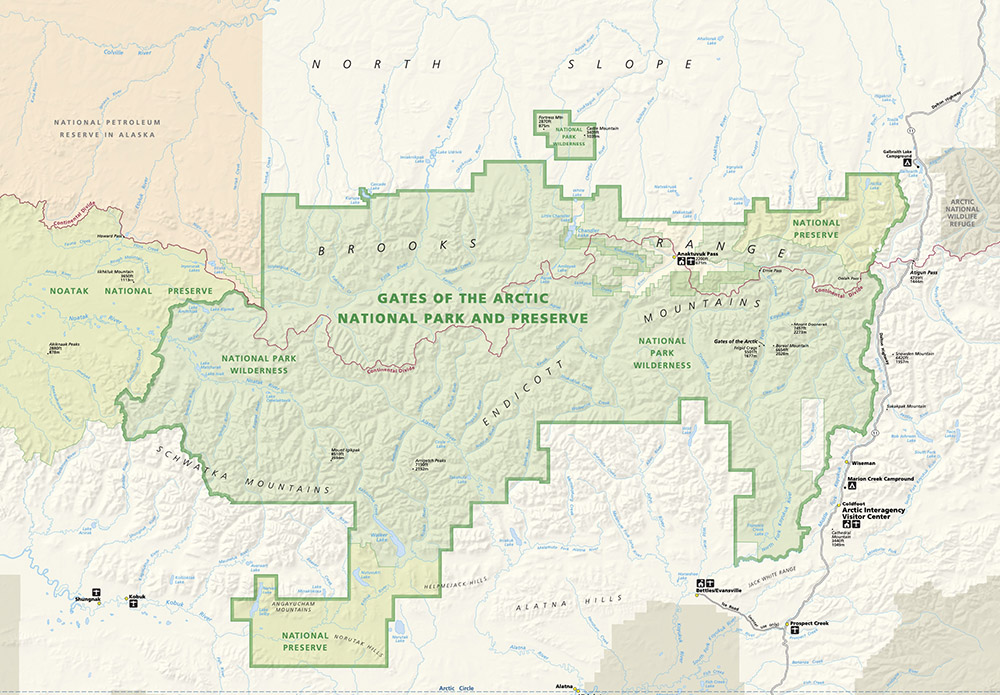

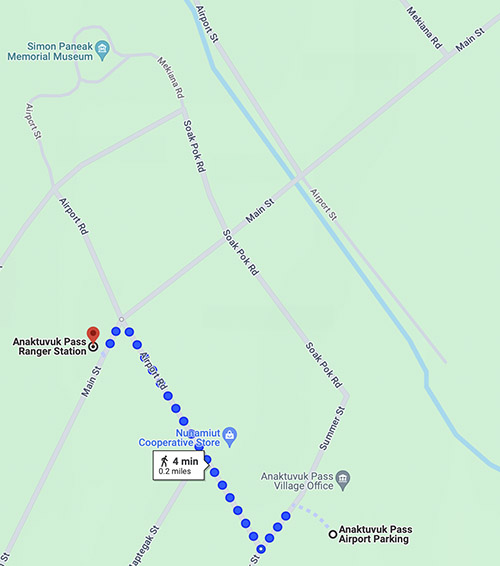

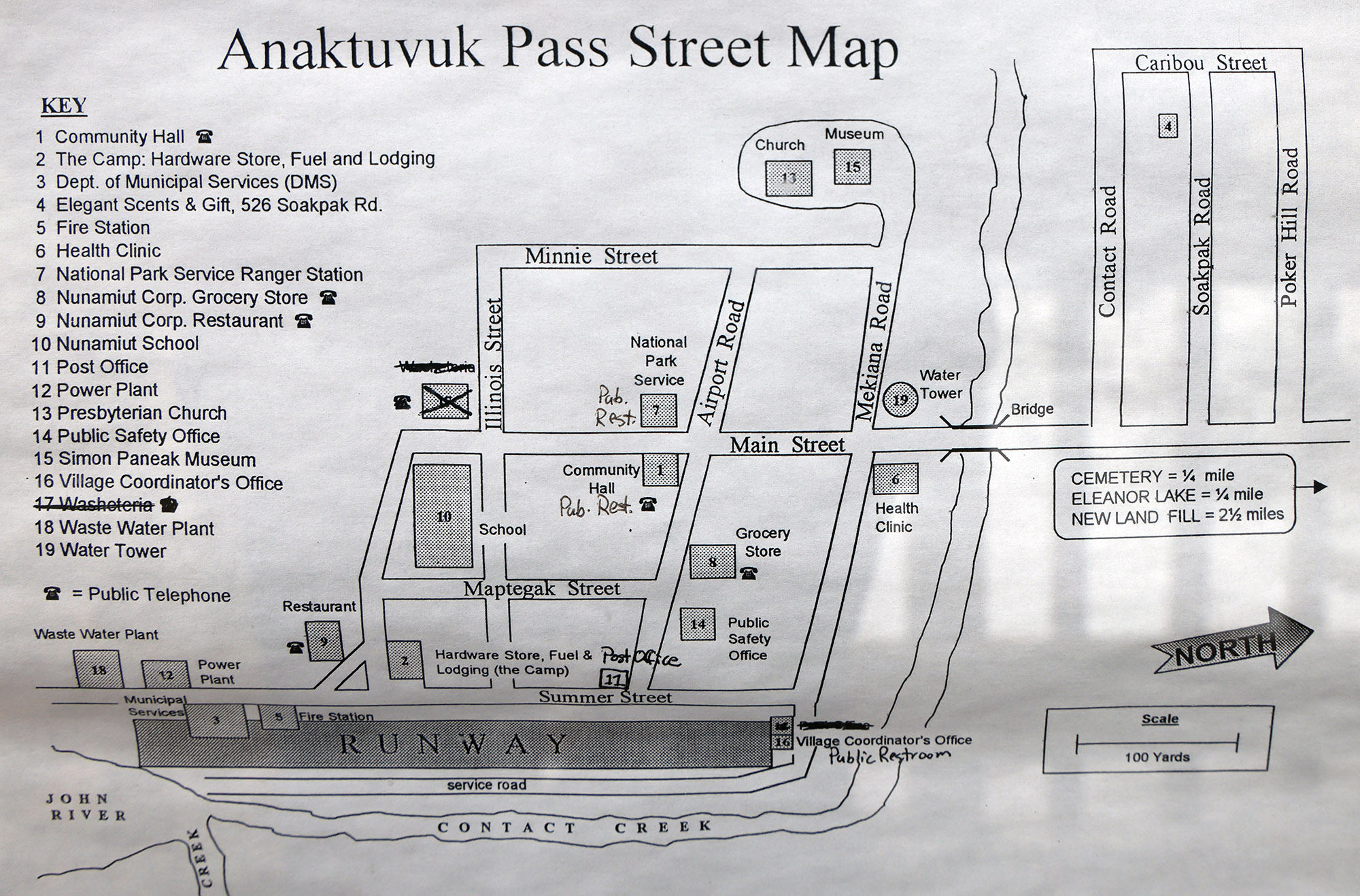

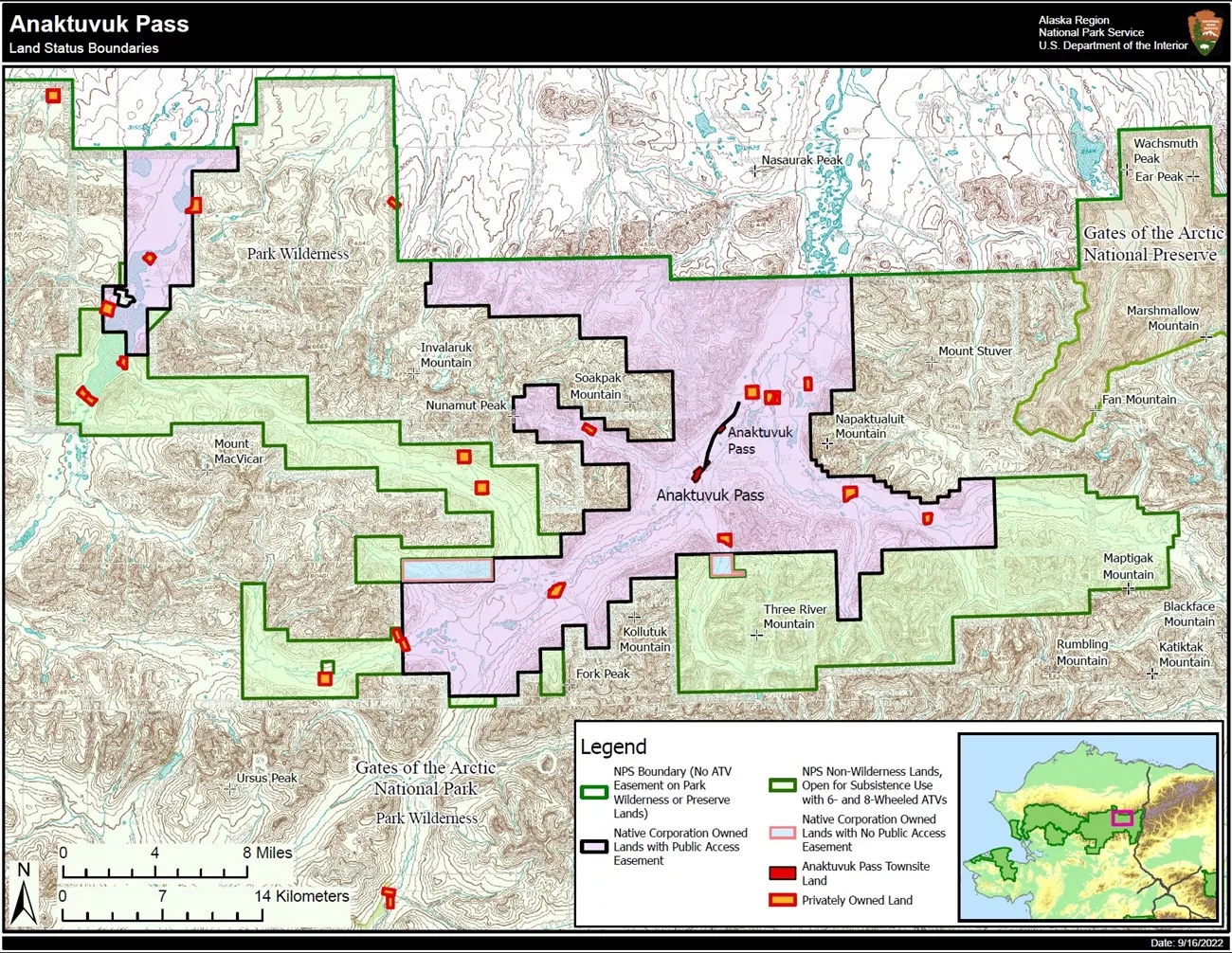

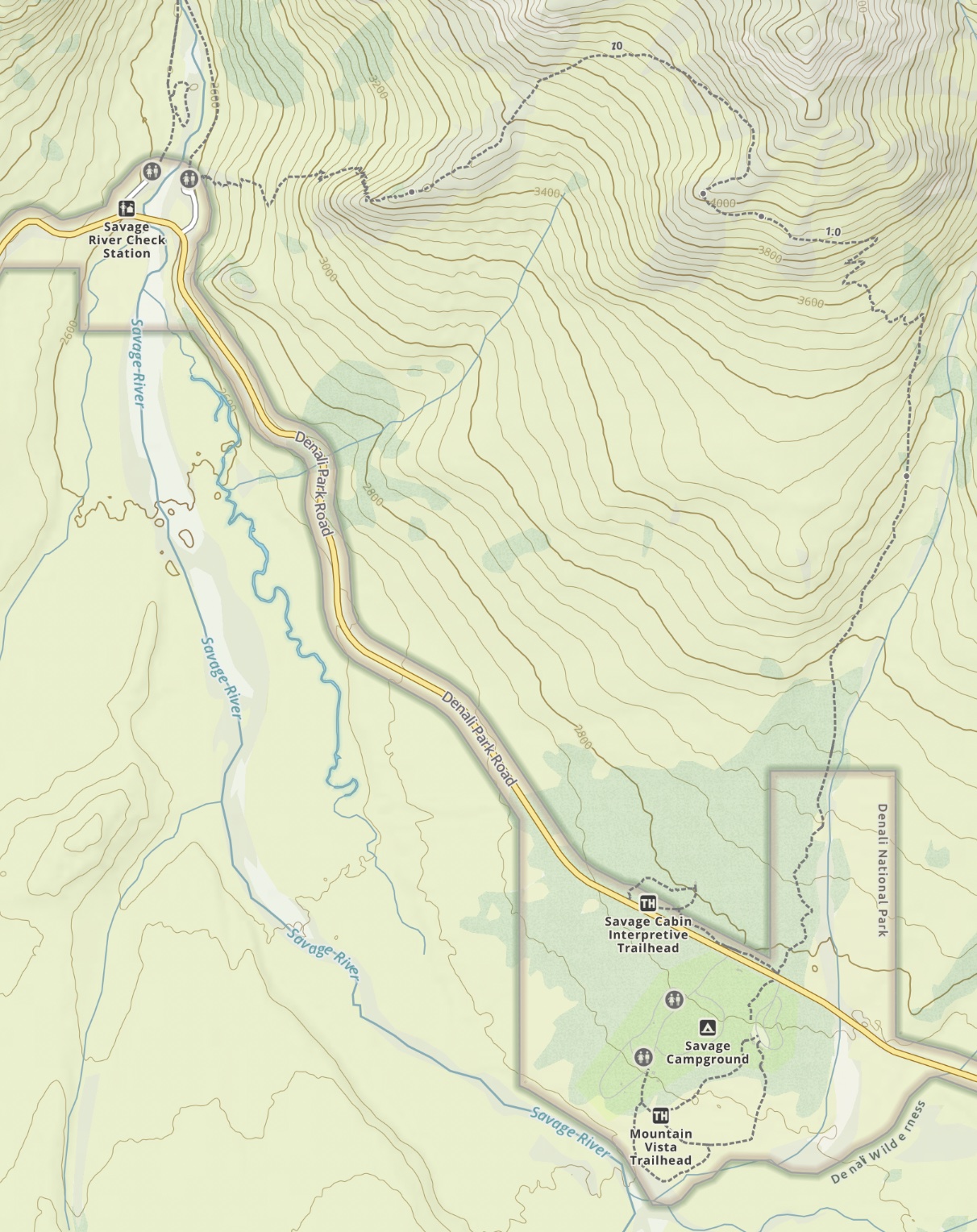

If you look at the map of Gates of the Arctic National Park, there appear to be two main pieces of land to the west and the east, joined by a thinner band that includes Anaktuvuk Pass. The initial proposal for the park considered two distinct units, separated by a north-south corridor comprising Anaktuvuk Pass. In the 1970s, villagers welcomed the establishment of the national park on their lands as a protection against outside development. Besides constituting the largest land conservation bill in history by protecting 106 million acres, the Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act of 1980 uniquely recognized the right of residents to continue a subsistence lifestyle in the newly established national parks, defining subsistence as:

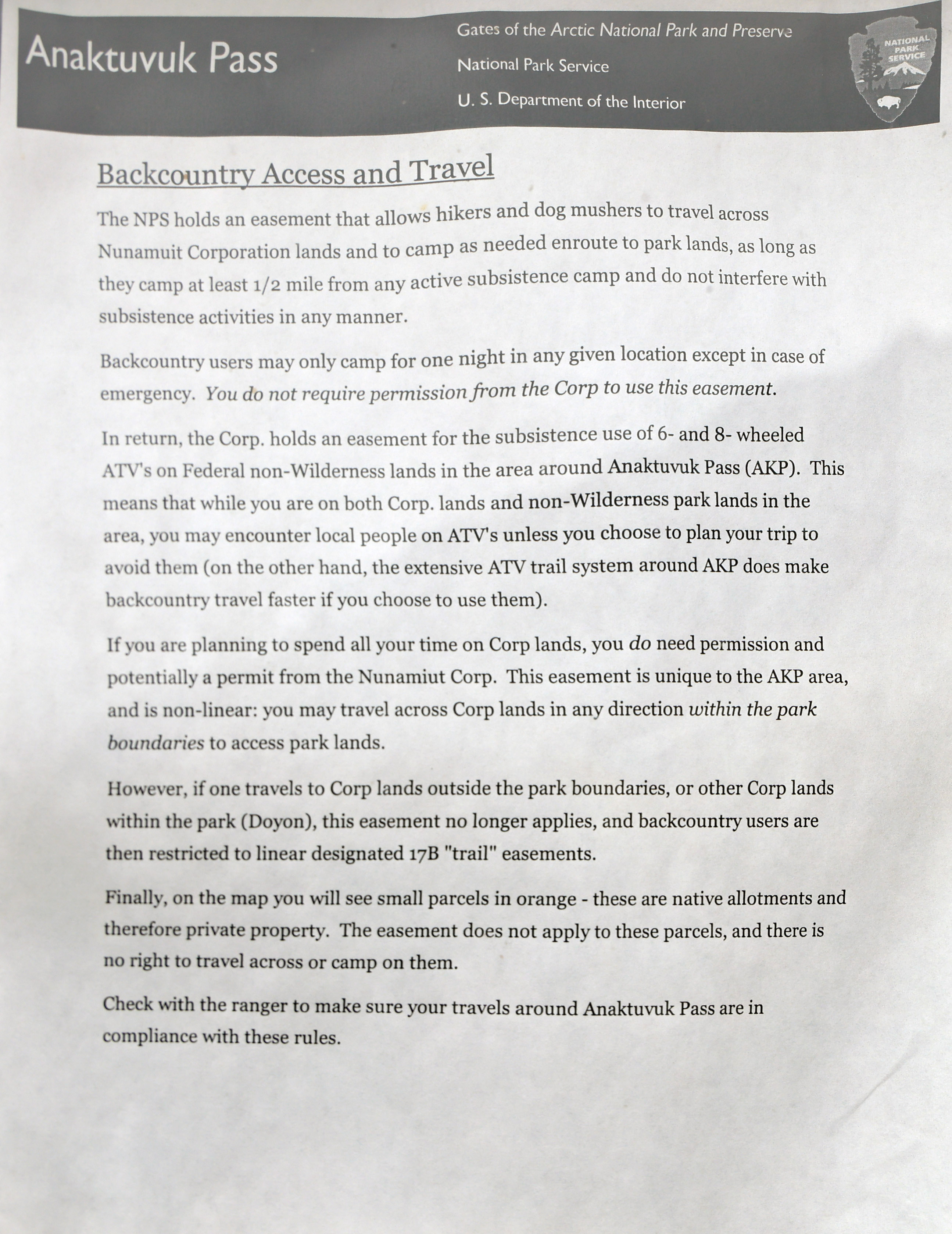

Customary and traditional uses by rural Alaska residents of wild, renewable resources for direct personal or family consumption as food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools or transportation; for the making and selling of handicraft articles out of non-edible by-products of fish and wildlife resources taken for personal or family consumption; for barter, or sharing for personal or family consumption; and for customary trade.The village of Anaktuvuk Pass, although included within the park boundaries, was designated as an inholding, which means that it is a private enclave surrounded by park lands but not subject to park regulations. The current boundaries of the inholding and a special non-wilderness park area were finalized in 1996 to allow residents to pursue their subsistence activities using motorized vehicles such as the amphibious six-wheeled and eight-wheeled all-terrain Argos ubiquitous in northern wet areas of the world, which are banned elsewhere in the park. The three types of lands: privately owned (light yellow), non-wilderness park areas (darker green), and wilderness park areas (lighter green) can be clearly seen in the map detail.

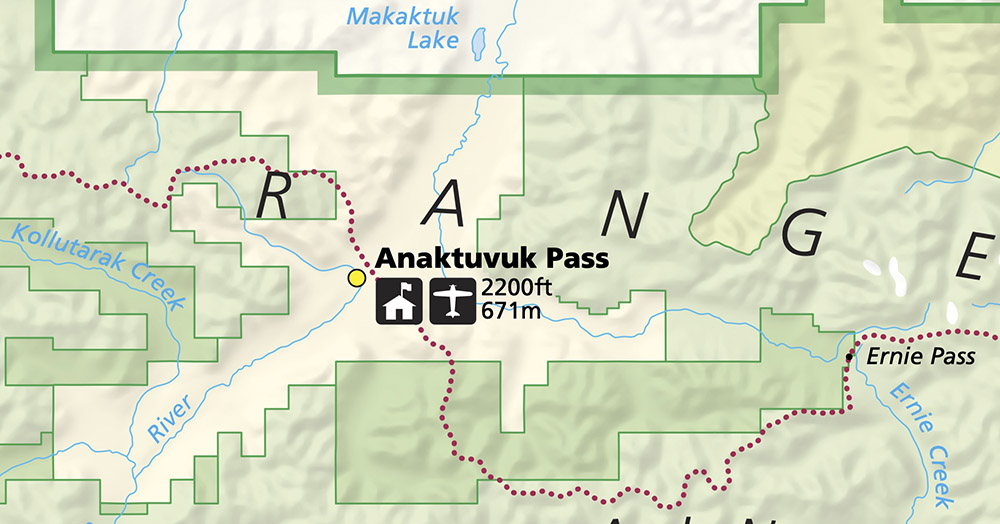

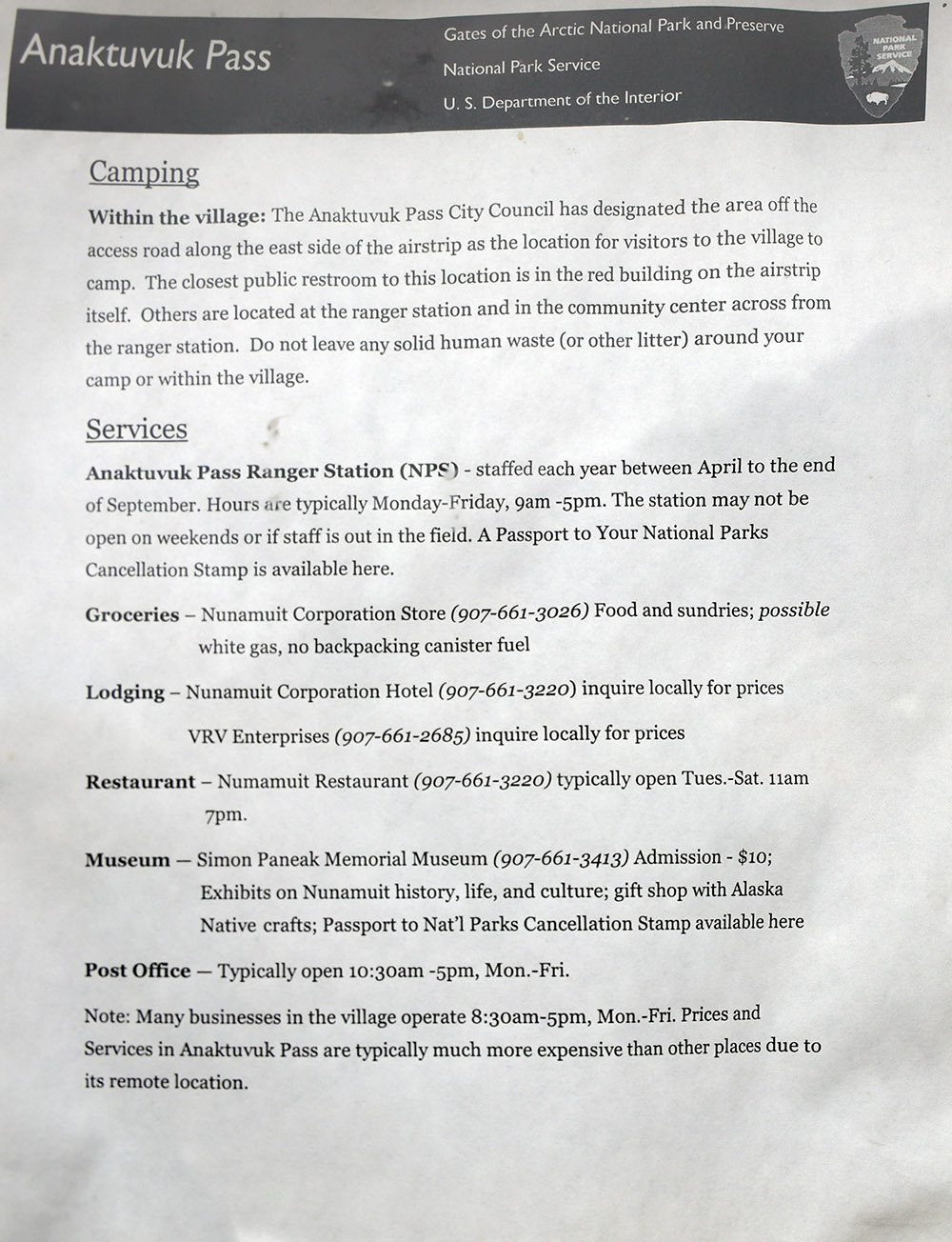

Since no roads reach Gates of the Arctic National Park, Anaktuvuk Pass has become a popular way to access the park. The village is equipped with a public-use airport that has even its own IATA code, AKP. This airport is served by scheduled flights, mostly Wright Air Service from Fairbanks ($190 per person each way), bypassing the need for expensive charter flights common in Alaska bush travel. You can leave luggage at their office, the planes carry camp fuel or bear spray, and the staff is professional. The morning of my trip, I had gotten up at 4:30 a.m. in the rain and we had driven from the main campground of Denali National Park to Fairbanks, stopping at a Walmart parking lot to repack for the flight. My friend Tommy returned the rental car at the Fairbanks International Airport terminal. Less than fifteen minutes before the departure for Anaktuvuk Pass, he could not find a taxi to get back to the Wright Air Service hangar located in the general aviation area. A friendly staff member gave him a ride.

On weekdays, Wright Air Service operates two flights that carry mail and vital supplies to the village. After the plane lands at Anaktuvuk Pass airport, it is quickly surrounded by native people in all sorts of vehicles visibly excited at the prospect of unloading goods. There are two lodging options and a free camping area, but visitors who do not venture into the wilderness generally come for a day trip. The morning flight left Fairbanks at 9 a.m., arriving in Anaktuvuk Pass at 10:45 a.m. Since there is also an afternoon flight whose schedule is more variable (ours left at 4:30 p.m.), day-trippers have several hours to wander the village streets, buy lunch at the grill (Nunamiut Corporation Camp Kitchen) or grocery store (Nunamiut Cooperative Store), strike up a conversation with the locals, tour a Arctic vegetable garden, and pay a visit to the Simon Paneak Memorial Museum which showcases Nunamiut culture and to the National Park Service Anaktuvuk Pass Ranger Station that holds the sought-after park passport stamper.

However, those few hours are hardly sufficient to set foot in the national park. Many think that since Anaktuvuk Pass is included in the boundaries of Gates of the Arctic National Park, just by landing they are already in the park, but the fact is that Anaktuvuk Pass is an inholding: privately owned land that is not part of the national park area despite being surrounded by it, as a close examination of the official park map will confirm. That land, owned by a native corporation, extends for a significant distance in some directions. The closest national park boundary is about 2 miles northwest of the village, with a 600-foot elevation gain. Although the area receives relatively little precipitation, 13 inch annually, as compared to the national average of 38 inch, due to the humidity, cloud cover, and low sun angle, the evaporation is low in the Arctic leaving the land suffused with water. Like in many Arctic flat areas, the tundra around Anaktuvuk Pass is wet. Because the permafrost (frozen soil), clay, and rock block surface drainage, there is standing water everywhere, and the only way to keep your feet dry is to balance yourself on unstable tussocks, which are like inverted potted clumps of grass without the pots. Hiking cross-country on the wet tundra and its ankle-busting tussocks is a lot of work compared to hiking on a trail or other solid surfaces. Do not count on hiking more than a mile per hour in that terrain. Corporation lands and some non-wilderness areas are crisscrossed by a network of unofficial ATV trails that make hiking easier – at the expense of the wildness, however, I do not know if there is such a trail towards the northwest, considering that the terrain around Soakpak Mountain, reminiscent of the mountains surrounding Banff in the Canadian Rocks (located at the “R” of RANGE on the detail map), is quite steep – also limiting hiking options.

When I first visited Gates of the Arctic National Park in 2000, I was surprised that the usually helpful park rangers declined to suggest specific itineraries. The rationale is that they want to spread land use by having visitors pick routes independently rather than concentrate on specific areas. They have a point. When I mentioned to the ranger stationed at Anaktuvuk Pass the date of my backpacking trip to the Arrigetch Peaks, he told me that I should be glad that I went back then, because in recent years a continuous user trail had been created. In most other places, this would be seen as an asset, but one of the reasons people come here is to experience untrammeled wilderness with no trace of human activity. In most other places, seeing dozens of hikers on a week-long outing is normal, but for Gates of the Arctic National Park, it is a circus.

(Click on map to enlarge)

I had spoken via phone to the same ranger, and indeed he did not want to provide ideas for a short, four-day outing out of Anaktuvuk Pass. However, after I had pored over maps and identified a hiking area, he confirmed its quality and explained the local rules: you can hike through and even camp in corporation-owned public access easements only on your way to federal park lands, but cannot use them for base camping. Apart from the reluctance to suggest an itinerary, the ranger was friendly and informative, making sure to lend us bear spray. With one notable exception, we did not encounter a single other person once we left Anaktuvuk Pass. To leave the same opportunity for solitude to future travelers, I will conform to local standards and not disclose our exact itinerary.

That exception was Jim, a native subsistence hunter with whom we rode on an Argo midway to our destination. Tommy and I took off in the rain from Fairbanks. For the entire duration of our flight, we did not see the mountains as they were socked in a low layer of clouds before landing in a drizzle at Anaktuvuk Pass. Since the season had been unusually rainy, we didn’t look forward to trudging through the low-elevation wet tundra where even the ATV trails were muddy. Because Wright Air had canceled the Sunday flights, our trip to Gates of the Arctic had been cut short by a day. Upon walking onto the airstrip, Tommy immediately noticed the eight-wheeled Argo and proceeded to convince Jim to give us a ride, eventually negotiating a very reasonable compensation for this time and gas. Jim also packed his riffle and ammunition in case caribou would show up. This didn’t happen – they are usually around town during October, however we got a sense of his hunting abilities when he spotted and identified a bear on a high ridge with his naked eyes, whereas even with binoculars Tommy and I were not able to find the creature. The bumpy but fun Argo ride was a highlight of our trip, and so was learning from Jim about his life in the Arctic mountains. I was amazed at the variety of terrain that the machine was able to navigate, basically anything on the tundra, including sharp banks, rivers, and deep mud. No wonder the Park Service had to craft a carefully balanced agreement with the native corporation to limit their use to a specific area.

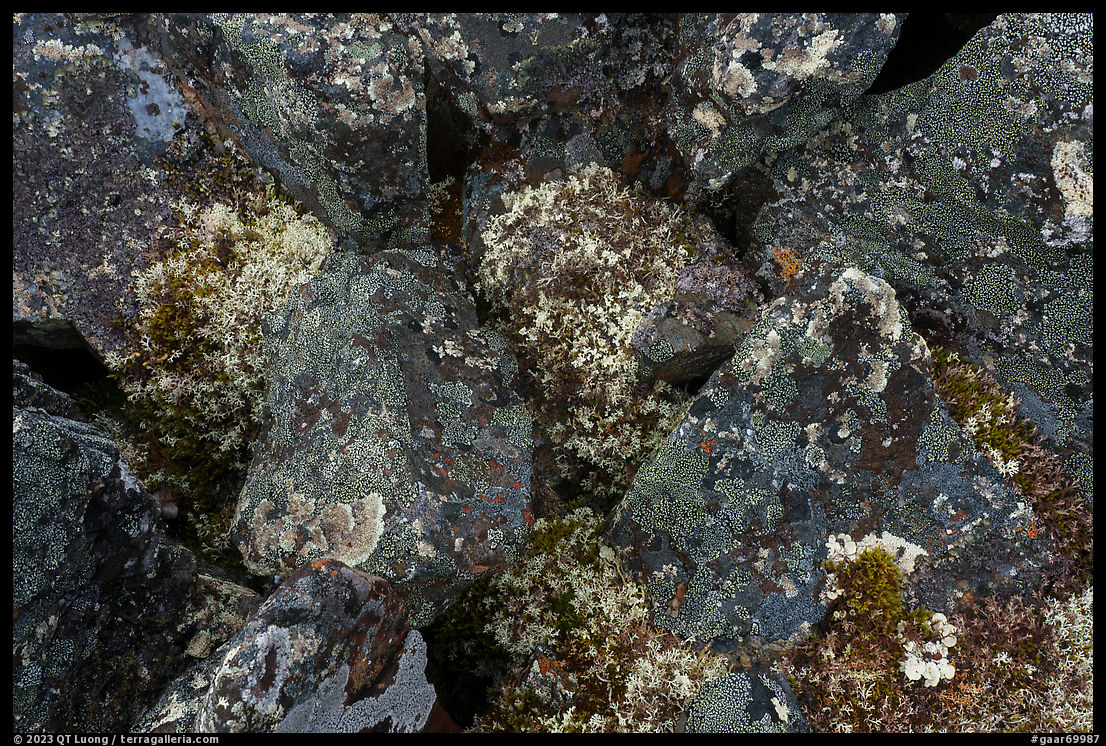

After following a broad valley, we arrived at the mouth of a drainage too steep and vegetated for the Argo. We bid goodbye to Jim and proceeded to climb up the drainage. Although we were less than four miles from the village, it was at this point a distant memory. Since we were in an area expressly withdrawn from designated wilderness to accommodate subsistence use, in theory, we could have seen traces of human activity, but this was never the case, and the land was as wild as any I had seen. With visibility limited by the weather, and with no trail to follow, I looked a lot at my feet, constantly marveling at the beauty of the ground, where each square inch was delicately alive in a different way.

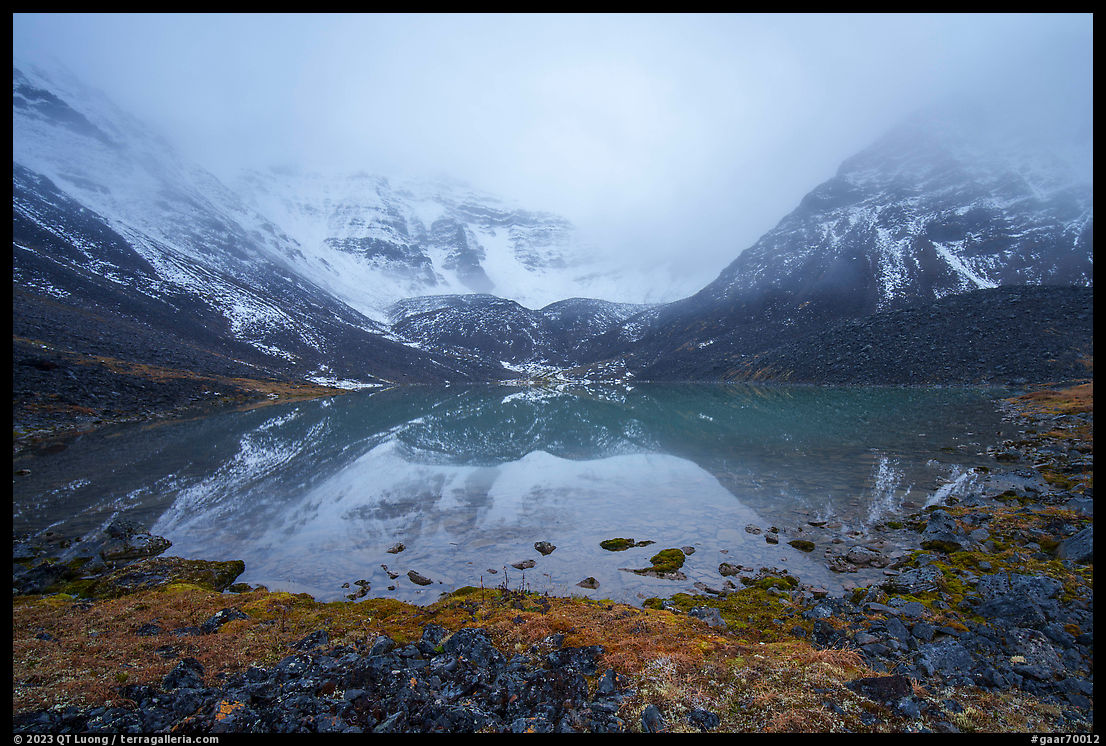

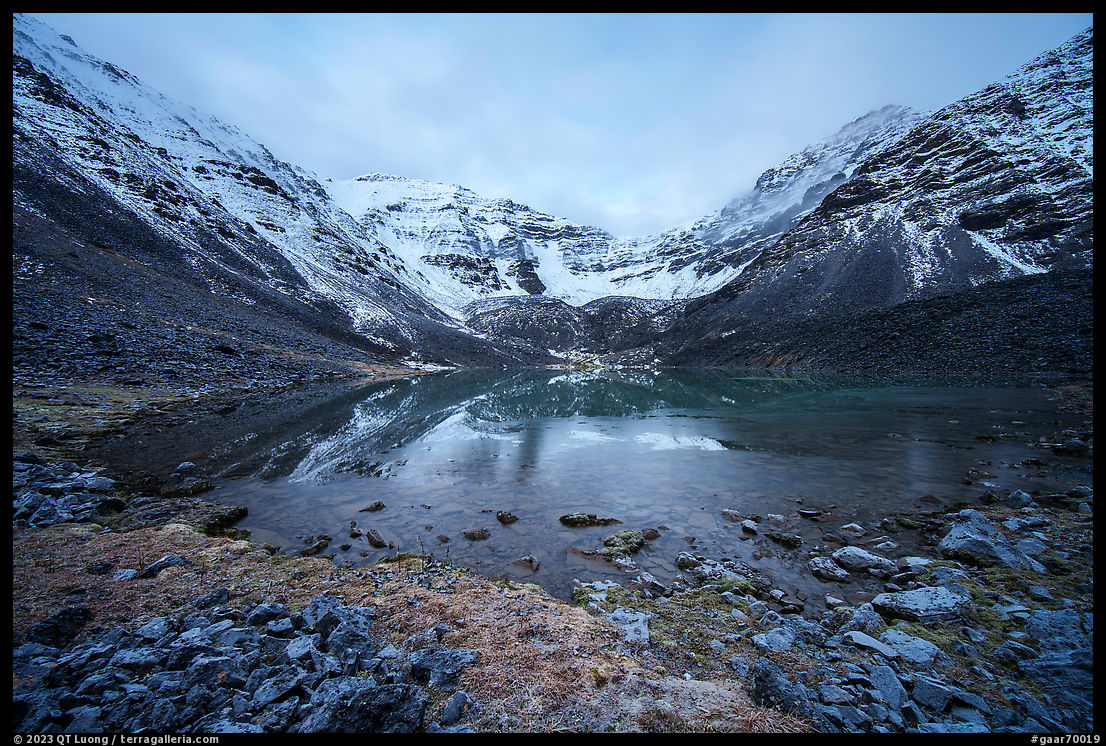

Since it was all unknown terrain with no prior descriptions nor trails, I had mapped a straightforward route that reached an unnamed mountain lake nested in a cirque of mountains by following its clear cascading outlet creek. Not only there would be no chances of getting lost, but also we’d be guaranteed access to water all the time. The key to easy hiking is to find the right distance to the creek. Too close often results in more brush and rocks, but too high causes you to go up and down ridges.

It was mid-September, a great time for hiking in Alaska because of the cooler temperatures, lack of biting insects, and autumn color. Occasional snow is possible, but not deep enough to strand the backcountry traveler. I was hoping to use the lake as a base camp to ascend the surrounding mountains, but when we got there, they were engulfed in clouds. One evening, after our camp dinner, the clouds lifted enough to show that recent snowfall had made the mountains tricky to climb without better equipment. Clouds moved back again, but when I woke up the next morning, the lake surface near the shore was covered with a thin pellicle of ice, the tundra was coated with frost, and the mountains were clear for the first time. The temperatures were in the mid-20s degrees F at dawn. The lake was located around 4200 feet elevation and the mountains culminated at slightly above 6000 feet, but the dusting of fresh snow made them feel more grand and wild.

On the way back to Anaktuvuk Pass, we enjoyed a day without rain and the sight of mountains that had been hidden in the clouds before. Anaktuvuk Pass is located at the edge of the north slope of the Brooks Range, the northernmost mountain range in America. The boreal forest reaches its northern limits a few dozen miles to the south. The absence of trees in that area of the park conferred it a distinct character from the park areas I had visited before. For Tommy’s first, and long-awaited trip into Gates of the Arctic National Park, I was pleased that despite its short duration, it was such a satisfying adventure and a great way to experience the park. In the mountains, we had the feeling of having entirely stepped away from civilization, whereas in the village we briefly connected with a different culture and way of life.

Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota (original color capture)

Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota (original color capture)