Photographing the Annular Solar Eclipse of Oct 14, 2023

2 Comments

The solar eclipse of October 14, 2023, was an “annular eclipse”, which happens when the moon passes entirely in front of the sun, but the lunar disk is too far from the earth to cover the entire sun, leaving a “ring of fire” around the moon. When I photographed such an eclipse in 2012, I prioritized an occurrence at sunset in a national park, from which the ring appeared as a crescent rather than a complete circle. I was therefore eager to watch the full “annularity”. More importantly, my immediate family was not with me when I executed an ambitious plan for the total eclipse of 2017. Since the next annular eclipse in the U.S. will be in 2046 and this event occurred on a Saturday, it was worth having the kids skip a few days of school. They were excited enough that they did not mind the long drive and outdoor living. We chose a location that would work for everybody in Great Basin National Park. Read on to see how I photographed there despite challenging conditions.

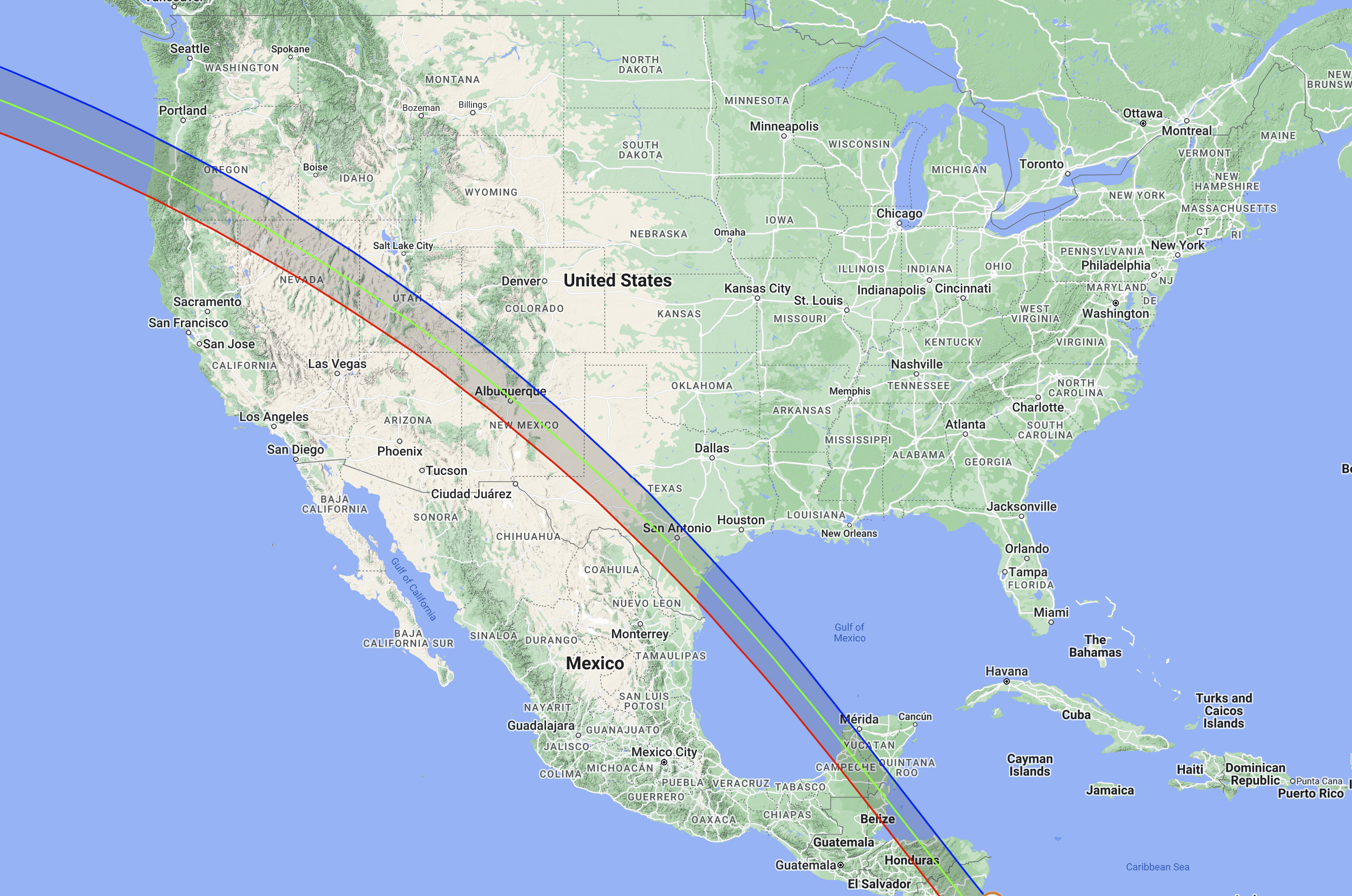

Choosing a destination

The path of the eclipse included several national parks and an even larger of national park units with intriguing possibilities, but most of them were located near the Four Corners (AZ/UT/CO/NM), a bit too far for a short road trip during a school week. I narrowed down the choice to three destinations: Crater Lake National Park, Great Basin National Park, and the Black Rock Desert – the site of Burning Man near Gerlach, NV. My first choice was the latter, because it was the closest to our home in San Jose, CA, and offered easy logistics. Dispersed camping is allowed anywhere on the playa, which would offer a landscape that might complement the eclipsed sun.

Three days before the celestial event, I checked the forecast for cloud cover. My favorite apps for that purpose are windy.com (not to be confused with windy.app which requires an expensive subscription to access the most valuable data) and meteoblue.com. Both, crucially for photography and sky watching, indicate the thickness of clouds at different altitudes. The forecast for eclipse day at the Black Rock Desert and at Crater Lake was very cloudy. The further east one went, the better it got, with just a few high-altitude clouds predicted for Great Basin National Park. I quickly devised a new five-day trip plan with stops at Lake Tahoe and Yosemite to break the driving days. We would drive to the park through NV-50, dubbed “The Loneliest Road in America” and back through NV-6, which is even more remote – within the 300 miles between Ely, NV and Lee Vining, CA, there is only one town with any services, Tonopah, NV.

Having made a last-minute change of plans, I didn’t expect to find any lodgings in Baker or Ely, especially since the National Park Service stated that it has been fully booked for up to 18 months in some cases. On Oct 13, traveling from Reno, we didn’t arrive in the park until the late afternoon, by which time all the park campgrounds were filled up. Like in most other national parks, car camping outside of established campgrounds is strictly prohibited within Great Basin National Park. However, the park is surrounded by public lands run by the Bureau of Land Management where dispersed camping is authorized anywhere. To minimize impact, it is nevertheless preferable to use existing sites, and we found one marked on the Gaia GPS map next to an abandoned corral and a tiny outhouse with a great view. The evening was promising, as no clouds obscured the night sky, one of the darkest in the country.

Choosing a viewpoint

My first idea was to view the eclipse at Lexington Arch. The trail ends at an opening on the west side of the arch, so although the sun would be a bit high (27.5 degrees above the horizon), it may be possible to frame the sun through the arch’s opening. However, the park service indicated that a high-clearance vehicle with at least all-wheel drive, but preferably 4-wheel drive was necessary. In addition, there have been multiple washouts along the road that have pushed the trailhead farther back, resulting in a 6-7 mile hike.

As an easier alternative, my second idea was to photograph the eclipse from the west shore of Stella Lake with the composition also including Wheeler Peak and the ridge of the mountain cirque (to the left of the photograph below) filling up the gap between the horizon and the sun. There were a few issues. Although the Google Earth Pro light simulation based on a digital elevation model showed that at the time of annularity, the sun would have cleared the ridge of the mountain cirque, I could not guarantee with absolute certainty that the ridge would not be blocking the path. In addition, we would have to hike in a hurry more than a mile in the forest and then wait at 10,400 ft elevation in potentially freezing early morning temperatures.

My wife was relieved when I abandoned that plan out of concern for the family’s experience. We could have watched the eclipse from the campsite, but since we got up at sunrise before 7am, I thought that we might as well drive further up the mountain to the Mather Overlook inside the park. We parked along the short spur unpaved road leading to the overlook and could take in the view of the valleys below and of the sky from the comfort of the van.

Besides the views, a benefit of watching the eclipse from high in the park was that we got a head start over the folks watching from below. After it was done, we easily found a parking spot at the trailhead at the end of the Wheeler Peak Scenic Road. Once we finished hiking the Bristlecone Grove/Alpine Lakes Trail, we noticed a long line of several dozen cars waiting along the road. Since the parking lot was full, rangers let one car in only when one car got down. As Great Basin National Park is normally one of the least crowded national parks, something like that would not happen on a normal day, but it was eclipse day!

Photographing the eclipse

Not wanting to watch the eclipse through an electronic viewfinder, and reasoning that capturing the changing phases of the eclipse would be more interesting than any single moment, I set up two time-lapse cameras on tripods. The first, using a wide-angle lens (24-105mm set at 32mm) would capture the eclipse within the landscape, whereas the second, with a telephoto lens (100-400mm with a 1.4x teleconverter for an effective 560mm) would provide a close-up of the sun. Although it is often stated that solar filters are necessary to avoid damaging your camera sensor, I figured out that this applies only to telephotos, since people photograph sunbursts with wide-angle lenses all the time. With the solar filter (Baader Astrosolar Safety Film cut to fit a square holder) the exposure for the sun was 1/100s at f/8, ISO 400.When we arrived, the sky was clear, and we watched the moon make the first contact with the sun through eclipse glasses at 8:07am. However, as the partial eclipse grew, clouds started to move in. By 9am the sun was totally obscured by a cloud. For the next fifteen minutes, we bemoaned that it was in the wrong spot since most of the sky elsewhere was clear. I stopped the time-lapses and considered driving to a different spot, but at about 9:16am, with only eight minutes left until the beginning of the full eclipse, the clouds thinned and we could intermittently see the veiled sun through them. It was a better viewing experience than a clear sky because eclipse glasses were no longer necessary. We could take in the sun, clouds, and landscape at once. I removed the solar filter from the telephoto lens, resulting in reasonable exposures between 1/500s and 1/1000s at f/8, ISO 100.

At 9:24am, the beginning of annularity, the moon made second contact with the sun, and the entire moon was in front of it. The eye easily tracked the ring of light in the sky, with the clouds adding a sense of motion that was mesmerizing – and would have made a great video if I had brought a third camera. However, I was disappointed that the wide-angle time-lapse did not convey the experience. You can barely see the sun in it because there were so many other bright spots in the clouds. Likewise, in a straight photograph, you have to look carefully to locate the ring of light, although on a reasonably large print it would have a solid presence even with the sun presented at its real size. However, a wide-angle composite would not work well when the sun played peekaboo with clouds.

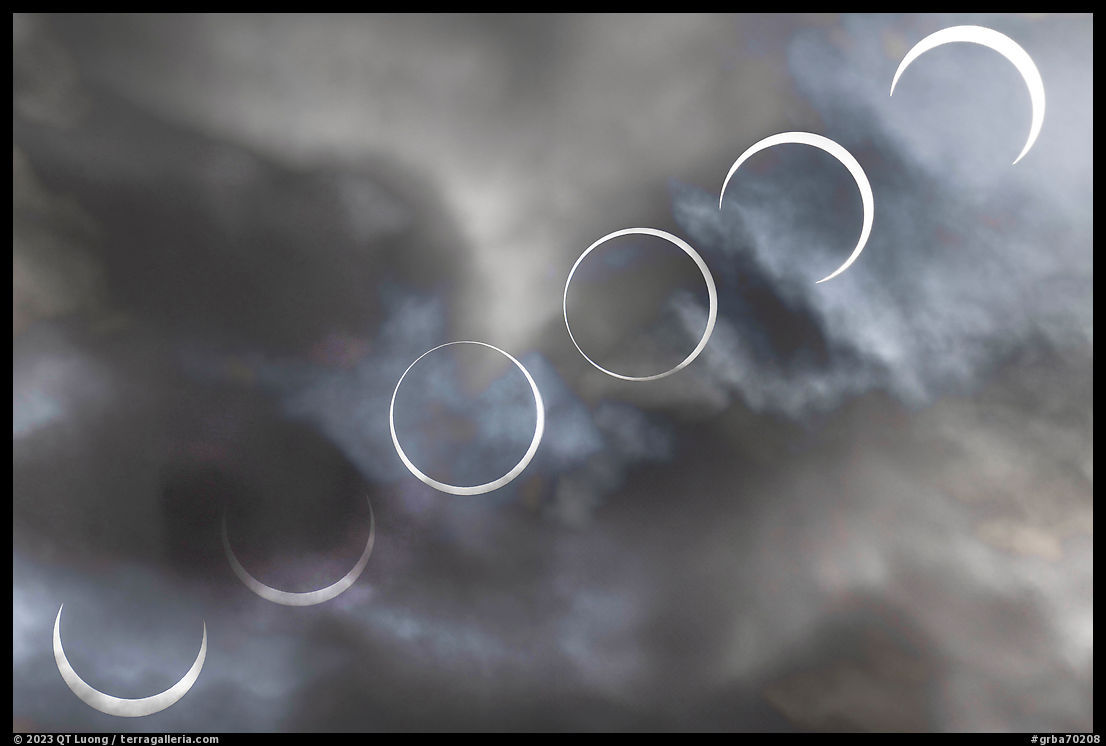

Naturally, in the telephoto time-lapse frames, the sun was prominent. Their more abstract character also make it possible to raise the contrast. During a total eclipse, the moon’s disk is totally dark, like a black hole in the sky, while the entire landscape darkens dramatically with a 360-degree sunset along the horizon. By contrast, during an annular eclipse, the light from the ring continues to illuminate the sky and the land. This eclipse was unique in that clouds were just thick enough to see the sun through. In front of the moon’s disk, those clouds danced, which was a mesmerizing and beautiful effect. There was no darkness like during a total eclipse.

The image below is a composite of six frames (including the two previous photographs from the beginning and end of the total annularity) at intervals of about two minutes, from 9:19am to 9:32am. I have not altered the pixel values, including the position and magnification of the sun, so it depicts accurately the size of the sun (via a 560mm lens) and its motion across the sky. My processing consisted of loading the individual frames in Photoshop layers with the mode “lighten” and creating a layer mask for each of them to set local transparency by painting, eliminating the brightest clouds that would have otherwise interfered with the suns.

Processing the time-lapse

I had photographed the sun close-up with the longest focal length that I had access to. The drawback of that choice is that the sun moved across the frame in a relatively short period of about fifteen minutes, after which I had to reposition the camera, placing the sun in the lower left corner. If the sky had been cloudless, realigning and extending the frames for a linear motion of the sun would have been relatively straightforward, since photographing the sun with the correct exposure through the solar filter renders the sky pitch black.However, each of my frames had clouds in it, and even after selecting only 25 minutes of timelapse (from 9:16 to 9:41) I needed a frame of 16000×12000 pixels to encompass all the individual frames (9504×6336 pixels), which meant that each of the individual frames had to be extended in a seamless way by that much. Earlier this year, Adobe had brought generative AI to Photoshop, with the new Generative Expand” feature. After you expand the canvas, if the prompt is left blank, Generative Expand fills the empty space with AI-generated content that blends with the existing image. Since this was the first time I tried this feature, I was very curious to see how it would work.

Although what you see above is weird, I was impressed that out of the 150 frames I processed, almost all of them were expanded plausibly. Those were the handful of exceptions. While the first four somewhat make sense, the fifth is something out of this world! After editing by hand those odd frames, fixing some errors that I made while capturing the sequence, and then reducing the luminosity of the clouds in some frames, I assembled a time-lapse – with frames 16000 pixels wide, which was the upside of my approach. Because of the frame extensions, it is not entirely truthful, yet the most important components, the sun, its motion, and surrounding portions of the sky are accurate. Nevertheless, I think that the timelapse gives a good sense of the memories one may have of this cosmic coincidence, as seen that day from Great Basin National Park. My main regret is to have used a 10-second interval, which was too long. Next time I’ll reduce that by half. By the way, if the animated GIF below doesn’t render well on your system, try the video, which has HD resolution.

If you photographed this eclipse, I’d enjoy seeing what you came up with. Otherwise do not forget the total eclipse of April 8, 2024. The next one in the U.S. will be in 2044!

Hi QT. I enjoyed reading about your adventure with the family to view and photograph the annular eclipse. You are more adventurous than me, though I did manage some passable images from the Bay View trail in the Hayward-Castro Valley area, despite significant cloud cover. And my location was only a 10-minute drive. Of course I didn’t capture the ring of fire from this location but it was a fun experience nonetheless.

Thanks, Mark. Considering the conditions, the image you shared with me was quite successful.