Are nature landscape photographs superficial idealizations ?

14 Comments

As many of my readers know, the exhibit Treasured Lands, currently at the National Heritage Museum, consists of natural, awe-inspiring National Parks landscapes big and small, mostly untouched by man. I have began to post those images to my new Facebook page, in the same sequence, and with the same comments as in the exhibit.

Last year, Mark Feeney, who won the 2008 Pulitzer Price for Criticism, wrote for the Boston Globe a review of that exhibit which, while praising images, concluded with this paragraph:

Also, it’s the pristine aspect of the parks that draws Luong, and understandably so, not their human aspect. No person is visible in any of the photographs, which is as it should be — except that it’s not. A national park is a human construction, a splendid and necessary one, but no less an artifice for that fact. A national park is not natural as, say, a glacier or canyon or waterfall is. This isn’t to ask for images of litter or traffic jams. But it is to note a highly limited, and effectively superficial, view of a subject whose magnificence owes something to its intellectual complexity as well as its environmental sublimity. One recalls the words of William Blake (no friend of dark satanic mills), “Where man is not, nature is barren.’’ Luong would disagree, but that there’s something sterile about these glorious images can’t be denied.

These comments are particularly relevant to the National Parks, whose mission since their creation has seen a tension between recreation and preservation. Of all the scenic places, ease of access and developed infrastructure has made the whole experience of visiting a National Park, particularly during summer week-ends, something more complicated and less relaxing than just immersing yourself in pristine scenes. Yet the pristine scenes still exist, can be experienced by everybody with a bit of effort, and are the reason the human constructions are there.

Beyond the National Parks, I see those comments as a criticism of not just this particular work, but of the whole genre of nature photography. There is a long (maybe too long for someone coming from contemporary art ?) tradition of photography – call it maybe the Ansel Adams tradition – which is about celebrating the beauty, delicacy, and grandeur of nature, untouched by the hand of man. Many of you work in that tradition, often in the hope that by presenting natural scenes in a way that evokes wonder, the viewers might be moved to want to preserve them. Does the fact that such an esthetic and perspective has been extensively explored in the past make it outdated or irrelevant ?

Given the reality of our world, do you think that representations of nature, without the presence or the hand of man, are escapism, or superficial idealization ?

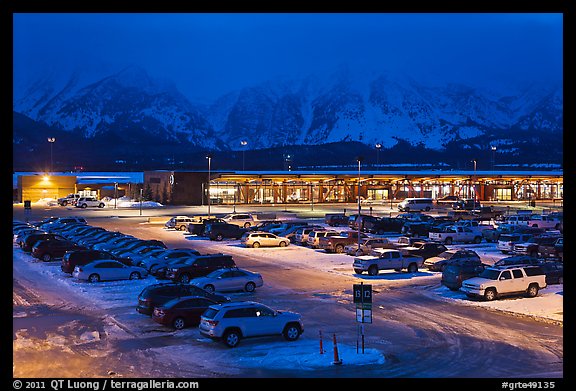

The above images are from my recent winter trip to Grand Teton National Park. All those scenes, including the airport, are situated within the boundaries of the Park.

Interesting comments from the critic, but I strongly disagree (which should be no surprise). I photograph to capture and convey what moved me in a particular place, and what moves me almost never includes any noticeable human elements (or even just humans!). I may be shoulder-to-shoulder with other people (usually other photographers) in a particular place–though often I am alone, which is a large part of why I do this–but I have no desire to include those people in my shots. They aren’t why I’m there, and they’re not what moves me. In all of my portfolio-quality images, I have exactly two which include people, and they serve specifically to give a sense of scale. Given what Mr. Feeney does for a living, I suspect that he’s looking for images that tell a story.

I, too, used to be a journalist, so I understand that to an extent. I had a portfolio review at last year’s POYi conference with a Pulitzer-winning photojournalist who had exactly zero experience with landscape photography. Her critique of my images was to shrug and tell me my photos needed to include people. I think she, too, was viewing my images as a journalist, and was looking for a story. What we do is not photojournalism, however, and I think some critics don’t fully grasp that. This may be another example of a critic who simply doesn’t see fine art landscape photography as an art form, thereby limiting it (in his mind) to a form of journalism, which it simply is not.

I don’t think it’s irrelevant at all. I think it’s backed up by the fact that we still have pristine and beautiful lands that are in danger of succumbing to the extraction of fossil fuels and mines. That alone is enough to show that this type of work is not only still wanted, but in some cases even required to ensure that we don’t forever alter a landscape for worse just for a temporary fuel supply.

More importantly, I think being the photographer of such places isn’t about showing off a place where there aren’t people or preserving a pretty place. I know for myself it reestablishes a connection to nature unobstructed by humans, where I feel something more substantial than just sitting on the computer getting some work done. I think having a person in the scene would serve as a reminder that it’s simply a getaway or a vacation. Showing a purely natural scene however, connects that root that Muir, Emerson and many more have said that we’re constantly connected to that gets lost in daily routines, whether we realize it or not.

Granted a national park is a man-made creation, so to speak, but it’s what’s inside of those borders, not the definition of those borders that make it so special. Inside of a national park is where people go to “reset” themselves and break free from normal day-to-day routines that prevent them from feeling something deeper that they can’t get sitting in an office. I see it all the time in Yellowstone – those who stay on the main roads and never really get away from the crowds are just having the same hurried vacations as the next people. But those who actually break away and get into the backcountry where there aren’t crowds and where you can find undisturbed nature feel a little bit freer and more aware of something special.

The role of God in modern life has changed. So the ‘landscape as God’ has become less relevant to people. A photograph must now be more than worship of an ideal. The first and only Ansel Adams photo I liked, Mt Williamson with boulders in the foreground was taken at a POW camp. He was not capable of any genre other than the idealised ‘lanscape as God’. I like the pictures posted above very much.

I totally disagree with the critic. When I look at nature landscapes, or take images myself I want to see nature as it looks in it’s original and pristine way. Not an image cluttered with human beings, cars or anything that comes with people. It’s not easy to get images that way, and that to me is one of the things that makes them even more special.

Just thinking to take a landscape in any area, not even a National Park is a daunting task to keep people, power lines, cars, lights, telephone poles etc out of the image.

I very much appreciate the natural landscape. Its a lot harder to shoot, takes more time to get to the remote areas, and to set up, but in the end the image is worth it all! It is wonder, splendor and magnificence that allows your eyes and mind to go to the peaceful place even if for just a few minutes!

One quick comment regarding something David said about Ansel Adams: I disagree with your statement that Adams was capable of producing only fine art landscapes. If you’ve seen his picture of Mt. Williamson, then you’ve almost certainly seen his other photos taken at Manzanar during WWII. Those images are one of the twentieth century’s most important works of photojournalism, and were instrumental in bringing attention to the plight of interred Japanese-Americans. Adams was indeed capable of moving easily between genres, which is yet another mark of his prowess as a photographer.

Hey QT

From the quoted article: “view of a subject whose magnificence owes something to its intellectual complexity “

That’s simply flat out incorrect … a view of the Tetons or Half Dome or Denali owes nothing to any intellectual complexity; in fact, it’s magnificence remains despite any intellectual complexity.

That said, I can’t but help be reminded of Steinbeck’s comment:

“For it is my opinion that we enclose and celebrate the freaks of our nation and our civilization. Yellowstone National Park is no more representative of America than is Disneyland.” — John Steinbeck (Travels with Charley: In Search of America)

I think landscape photography is reasonably labelled a superficial idealization; the fact that it might be art, and not photojournalism, doesn’t negate that. Most art is superficial idealization; but so is much of being human. That’s not inherently a bad thing.

Cheers

Carl

Mr. Feeny’s comments are very similar to what people have said about landscape paintings for the past 500 years. In the 1500’s – 1800, landscapes were viewed as a ‘lesser art’ because they had no message or story, especially in Europe where stories about God or the Christian Bible were held in high esteem. In the late 1700’s, landscapes became more highly regarded as representations of God’s work and later because appreciated just for their beauty when cities became more crowded.

But when ‘modern art’ came along around 1900,landscapes once again because unimportant compared to the psycological messages and important concepts being described in the art of the day.

To someone looking for a statement, a landscape will be boring. I had a super high level art critic view my work and he almost yawned, despite my work having many dozens of millions of views on the internet.

I guess landscapes appeal to the ‘common man’ according to the art critics.

Too bad for them! I look at some ‘modern art’ paintings and pictures that sell for millions that I would not even hang on my wall. But I do like some of them. To each, his or her own.

Patrick

It’s not surprising to get such a review, particularly when the critic is probably not much of an outdoorsman. I’d say consider the source.

I agree with Carl for the most part. Most photography is an idealization. It has to be because it is only showing a limited part of a scene of the photographer’s choosing no matter the genre, and only for a brief moment in time. That is just the nature of the medium but it doesn’t make it any less of an art when it comes to emotional impact.

Thank you everybody for the comments so far.

The role which was played by God in earlier art is being replaced by Nature.

Ansel Adams was clearly a versatile photographer (and liked to emphasize that in his choice of portfolio images) since commercial photography helped him to make a living for most of his life. However, that’s mostly his nature images that establish his position and legacy as an important artist – look for example at “Ansel Adams at 100”.

Mark Feeney clearly states that he is not an outdoor person “I spent the next afternoon at Mesa Verde, the cliff-dwelling site that became one of the first national parks. May the spirit of John Muir forgive me, but I had a much better time at the theater.” However, if it was necessary to be an outdoor person to be touched by the work, I would have considered it a failure, given the goals I set out to accomplish in the National Parks project.

Robin, Rachel and Patrick comments seem to illustrate Feeney’s point. If it is difficult to find pristine views, and you are seeking them because that is what you had in mind or because your normal environment is crowded, then the pristine views do indeed show an idealization of what’s there, rather than showing what’s actually there.

My personal take is that they are indeed idealizations (like Carl and Richard said) but they are not superficial, outdated, nor irrelevant. Although they may have little cultural relevance (a tenet not just of journalism, but also contemporary art) there are some truths to be learned from them. Although the genre has been thoroughly explored before, the general public may respond differently to the work of a living artist than to Ansel Adams. The National Parks may be already some of the best protected lands in the world, yet I saw the NPS welcome with a great deal of excitement the Ken Burns series because it brought awareness of the parks to many. Nature photography can still do that too.

QT —

I differ with the reviewer. Landscape photography is not photojournalism and your images do not profess to be photojournalism.

The landscape photographer seeks to convey a message about what he/she sees, feels and reacts: his or her emotional response to a place. Are abstracts escapist? Are intimate landscapes escapist? Both, of course not, yet both can be highly expressive of the photographer’s vision of the landscape.

Yes, most of our national parks do have some or a lot of development. In the case of Grand Teton, much of the development is a reflection of the history of the park. The park/prior national monument initially included only the mountains. Expansion to include the valley floor came only after much of the floor had already been settled resulting in many “in holdings” in the park including Jackson airport. Other parks have development driven by the park service efforts to attract visitors in the 1960s when that was in vogue. Development can be a legitimate subject for a photographic project but I would argue that project is a photojournalism project, not a landscape project.

Frank

QT –

Though I am a big fan of your photography and I am a dedicated outdoor/nature photographer myself – I can’t dismiss the critical comments like many other (nature photogs) doing or will do. Acknowledge or not – that’s the way nature photography is seen by most art critics and a large portion of art community. We, nature photographers, blssfully ignore that and create our photos – thank god for that.

There is nothing wrong with the capture of natural beauty – but most landscape photographers get stuck just there and dont go beyond that. Ansel Adams and others were the pioneer of this field – but repeating the same style will not take this genre anywhere. Landscape photography does not have to become photojournalism – but it needs to go thorugh more creativity and experimentation – in other words, it needs to evolve from where it is now to gain more respect

The reviewer’s comments are typical anthropocentricity. Plain and simple.

As a budding nature photographer, When I photograph nature, all I see are stories.

Mr. Feeney’s criticism is a perfect example of the critic not understanding what he is criticizing. It shows again that just because someone has a Pulitzer, that person is not necessarily immunized against ignorance. Whether this applies to Mr. Feeney or not, the Eastern art establishment took a long time to have any comprehension of Western photography of the natural scene, or even of any of the aesthetics of the West at all. Mr. Feeney’s comment about Mesa Verde says all we need to know about him. The idea that nature and art depicting it must somehow answer to intellectual expectations and constructs completely misses the point.