New River Gorge National Park and Preserve: Five Unexpected Sights

No Comments

When I planned my well-awaited trip to New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, I was expecting to photograph the landscapes of the New River Gorge and the most famous landmark in West Virginia, the New River Gorge Bridge. What I didn’t expect to find were so many historic structures that the place often felt like an open-air museum of America’s early industrial days. I knew that the New River was famed for its whitewater, but I did not expect so many waterfalls ranging from stream cascades to a 1,500-foot wide waterfall – the widest in any national park. This article, companion to the previous one about classic sights of the New River Gorge details those unexpected sights.

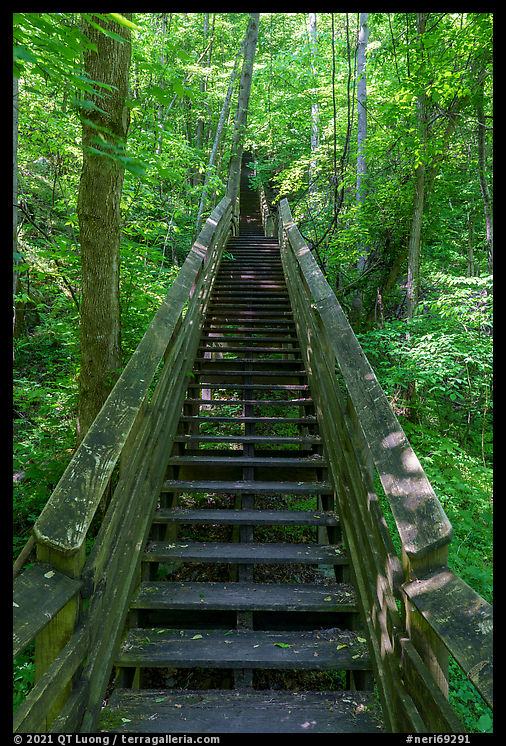

Kaymoor (6)

The New River Coalfield was one of the most prosperous coal mining regions in the country, with dozens of mines located in the gorge. Its coal was renowned for its low smoke emissions. Kaymoor was one of the biggest coal mines in the area. It drew workers from all around the country who lived in a company town of more than 100 houses. Because the NPS did not remove vegetation, the site offers the evocative atmosphere of ruins reclaimed by the jungle, making it one of the most eerily beautiful ghost towns in the area. As a forest scene, it is best photographed on cloudy days. Kaymoor had multiple levels, once accessed by workers via a steam-powered “mountain haulage” tram. The Kaymoor Miners Trail (2 miles roundtrip, 760 feet elevation loss) travels that same steep terrain. In the first half, switchbacks lead to the remnants of the Keymoor mine, where safety signs reminded me how dangerous the job was. In the second half, a wooden staircase with 821-steps next to the rails of the dangerous-looking tram leads to the old coal processing structures, abandoned train tracks, and old coke ovens.

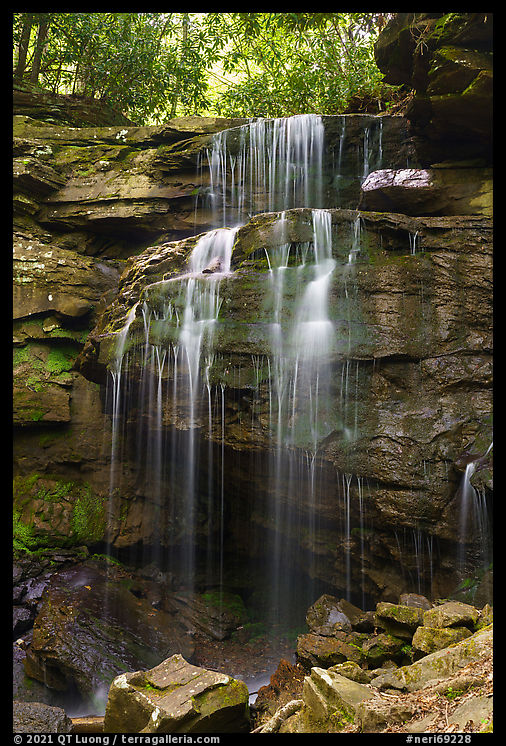

Nuttallburg and Keeney’s Creek (5)

For centuries, the gorge remained inaccessible along its entire length. In 1873, the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) railroad opened this isolated part of West Virginia. That year, John Nutall became the second mine owner to ship coal using the recently completed railroad. From 1920 to 1928, the famous industrialist Henry Ford leased the mine. He updated its equipment, designing and building many facilities still standing today, including the remarkably well-preserved 1,385 feel-long conveyor that descends from the hill to a tipple above railroad tracks. The mine would operate until 1958, and in 1998 the Nuttall family transferred ownership of Nuttallburg to the National Park Service (NPS). Almost fifty towns sprang up along the New River in response to a growing nation’s need for coal, but none is as complete as Nuttallburg, one of the prime coal-related historic sites in the United States. I explored the bottom of the site and its impressive structures via short and flat trails, accessed through a road passable by passenger cars, although sometimes one-lane and unpaved. On the way, that road follows Keeney’s Creek, where I noticed beautiful cascading waterfalls. The mine entrance at the top is best accessed through Beauty Mountain Road on the rim.

Thurmond and Dunloup Creek Falls (7)

Acting as a hub for the mining communities within the gorge during the heydays of coal mining, Thurmond was the busiest depot along the entire C&O line. Its two banks, used by coal barons, were the richest in West Virginia. Although settled in 1844, the quintessential railroad town wasn’t accessible by road until 1921. Its commercial district still lacks a road, and its buildings curiously stand just a few yards away from the rail tracks where trains still thunder. Using a perspective-control lens, I maintained the parallelism of their west-facing facades in the image. In its prime, Thurmond had 500 residents. At the 2019 census, the population was four, making it the smallest town in West Virginia. However, the historic train depot is still active and serves as an Amtrak stop to New York or Chicago. Thurmond is reached via WV-25, a narrow and winding road that follows Dunloop Creek. About 8 miles from US 19, look for 20-foot Dunloup Creek Falls, a waterfall with a good year-round flow. The road reaches Thurmond by crossing the New River on an odd single-lane car and train bridge combined.

Glade Creek and Kate’s Branch Falls (10)

Despite following a steep canyon, the 6-mile long trail (1,400 ft elevation gain) along Glade Creek, one of the longest in the park, is easy, as it uses an old railroad bed. For all of its length, it hugs Glade Creek, along which swimming holes alternate with cascading waterfalls, including Glade Creek Falls, about a mile from the lower trailhead near the New River. I soaked in the peaceful atmosphere created by the constant sound of moving water and the green foliage. A polarizing filter helped make the tiny cascades stand out from the darkened water.

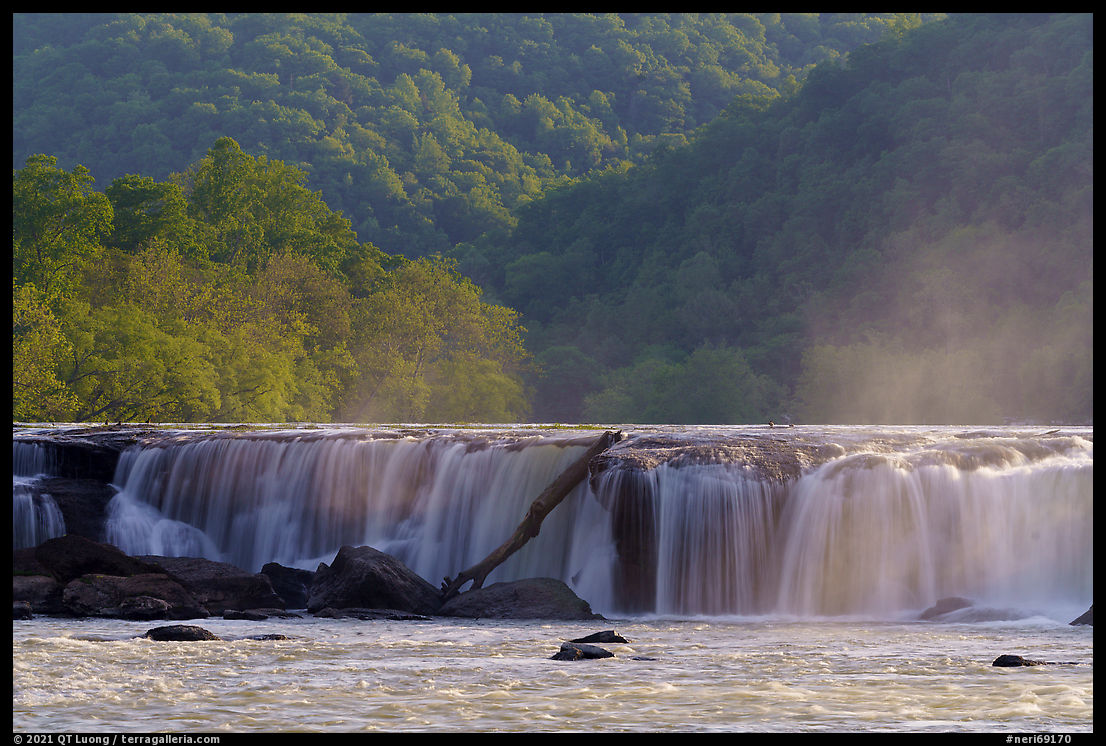

Sandstone Falls (9)

What makes Sandstone Falls such a spectacular sight despite its modest drop of 15-25 feet is its 1,500-foot width. The largest waterfall on the entire New River is also the widest I have seen in any national park. For its whole width, the river drops here in a stairstep cascade, broken by mid-river islands. They are home to one of the region’s most unique ecosystems, the Appalachian Riverside Flatrock Community, best explored along the 0.5-mile Island Loop Trail on the island on the side opposite to the falls. A quarter-mile-long boardwalk and bridge system links the islands, offering easy access and multiple viewpoints from which I could see the falls at a distance. However, traversing the last 0.15 miles for a close view of the waterfall was a bit more adventurous. I followed a user trail from the end of the boardwalk and crossed no less than three streams. From the western shore of the last island, I stood in awe right at the edge of the all-encompassing raging water, and composed with a wide-angle lens. The falls benefited from the soft light of open shade in the late afternoon, while sunlight still highlighted the hills. Sunset had a more colorful sky, but the slower shutter speed rendered water with less texture. Sandstone Falls is less than two miles from the Sandstone Visitor Center as the crow flies, but by road, it took more than half an hour of scenic driving. You drive south on WV-20 to the historic town of Hilton before crossing the river and heading north on the opposite bank on the only road in the park that closely follows the river.