When I

photographed in the Alps in the early 1990s, I didn’t even own a tripod. My camera support of choice was a clamp that could attach to the adze of an ice-ax. Upon arriving in America in 1993, one of my first purchases was a tripod. Many photographers have wasted money by starting with flimsy tripods, but at that point, I already knew enough to go directly to a good one. Today, there is a dizzying array of tripod offerings. At that time, the choice was essentially between Gitzo (twist lock, expensive) and Bogen (flip locks, economical). Even though I was envious of how fast my roommate folded his Bogen, it was an easy choice, given how everything

Galen Rowell did influenced me. In this write-up, I’ll tell you why I moved from one tripod to the next, and in the process quickly outline the strengths and weaknesses of each of them.

Gitzo

In 1993, Gitzo’s line of tripods was quite simple. They came in series from the smallest to the largest, denotated by a number from 0 to 5. Within each series, you had a choice between 3 sections and 4 sections. The larger tripods (series 3 and up) offered a choice of a regular, geared or no center column. I bought their series 2, 4-section tripod. Only one year later, Gitzo announced the first carbon fiber tripod, the Mountaineer (initially only available as a series 2). It promised a savings of one-third the weight, better mechanical characteristics, and no hands frozen by contact with bare metal. Its price of several times more than the aluminum model, was unheard of for a tripod. However, the innovation was irresistible, and I quickly made the switch, reselling my not-so old tripod. I bought a 3-section tripod rather than 4-section. For general use, the more compact folded size of a 4-section tripod was not worth the additional setup time and the diminished rigidity caused by one more joint and smaller leg diameters.

I would supplement it with a series 1 tripod primarily for travel and a series 3 for large-format photography (Gitzo 1325, 2035 grams; with RRS BH-55 head, 2900 grams), both carbon fiber. No going back to aluminum! I tried to use the series 1 for a while on trips with long hikes, even with my 5×7 camera. After making a photograph at the bottom of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, I secured the tripod to my backpack. As I shouldered it in a swinging motion, the tripod detached itself and fell into the raging waters. My large-format camera was now useless without a tripod, and I scrambled up the gully quickly to try to catch a sunset photograph at least. The Gitzo series 1 weighs 1160 grams versus 1440 grams for the series 2. Remembering my times with the series 1, I did not think the savings in weight were worth the loss in utility (less stable, smaller height) and subsequently used the series 2 even for long hiking and traveling. When working closer to the car, the series 3 was my choice, especially on windy days when its improved rigidity made a difference.

The Mountaineer tripod lasted me until the early 2000s when it became inoperable. It was all my fault. Among other outings, I had taken it on a two-week kayaking trip in Glacier Bay National Park. Due to the lack of space on the kayak, I lashed it on the kayak’s hull. During a trip to France, I walked into the Gitzo factory in the suburbs of Paris, looking for service for its overly tight legs. The technician explained that they had swollen due to repeated exposure to saltwater. I made a mental note to always rinse my next tripod (Gitzo 1227), basically an evolution of the same model, after any use in saltwater.

One of the inconveniences of the Gitzo twist locks is that you always had to make sure you unfold or fold the legs in the proper order. If the sequence was wrong, the legs would spin frustratingly. Each time I handed the tripod to a non-photographer friend trying to be helpful, they never succeeded in locking the legs. Although using the correct sequence had become second nature for me, after a few years of Gitzo introducing an anti-leg rotation system, I upgraded to a Gitzo GT2531 (discontinued, current is GT2532) because my old tripod’s operation was no longer as smooth as when new, with one leg lock tending to slip.

A few years later, that tripod began to develop a problem I didn’t have at all with my previous Gitzos: the pivots at the apex became loose. Curiously, tightening the screws (with an annoyingly non-standard key) did not help. My brother-in-law, a mechanical engineer, tried all sorts of ideas to fix that problem of floppy legs, but the issue always re-occurred once in the field. In the while, Gitzo had been acquired by Manfrotto, and their technical support was irresponsive. It wasn’t until many years later that I was able to fix that tripod by cannibalizing parts from my older (the one without anti-leg rotation) tripod. Meanwhile, I needed an entirely functional tripod and the premium price of the Gitzos did not seem justified anymore.

Induro

By the early 2010s, several manufacturers offered Gitzo-inspired tripods. You could tell it was so because of their nomenclature, which closely followed the Gizo series numbers.

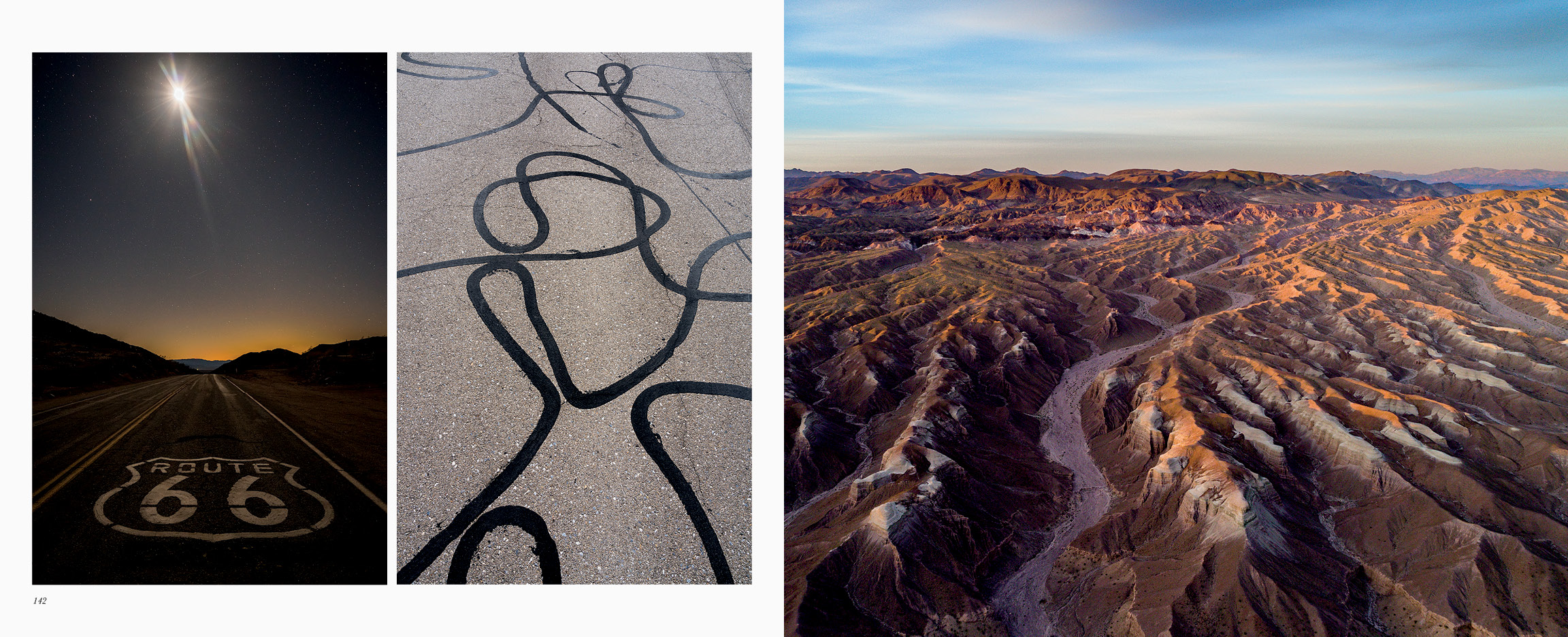

Needing a second tripod for a winter trip to Alaska, I bought an

Induro CLT-203. The 2 stands for series 2, and the 3 for the number of sections. A series 2 from Induro had weight, leg diameters, and heights quite similar to a series 2 from Gitzo. Although a bit heavier (1575 grams) and a tad less rigid than the Gitzo 2531 (1440 grams), it appeared reassuringly well built. It came with nice extras such as a carrying case, built-in foam tube covers that are great in freezing temperatures, interchangeable feet, all for a lower price than the Gitzo. Since I anticipated using it in the snow, I purchased specialty snow feet that included baskets similar to the ones found on ski poles. One evening, I set up a medium telephoto for a long exposure of the road at dusk. I waited for a car to drive by so that the red of its tail lights would make a red trail against the blue tones of the snowy landscape. After reviewing the image on the LCD, I was disappointed that it wasn’t sharp due to motion blur. Traffic is not too frequent along the George Parks Highway, so it took a while to make a second and third attempt, with the same results. By that time, the window of opportunity with the right light levels was gone – and we were freezing. Just as a test, I borrowed my friend’s tripod to photograph the empty highway, and the image turned out sharp like the one he previously made.

When using the Induro in the snow for northern light exposures up to 15s, the images were sharp. However, I couldn’t shake up the memories of the evening on the George Parks Highway, and upon coming home, I returned the tripod. It was only several years later that I thought of a possible explanation for what had happened. The snow feet, instead of ending with a rubber tip, had metal tips and somehow they may have been responsible for amplifying vibration, rather than the tripod itself. But that was not the end of Induro.

Feisol

After returning the Induro, I bought a

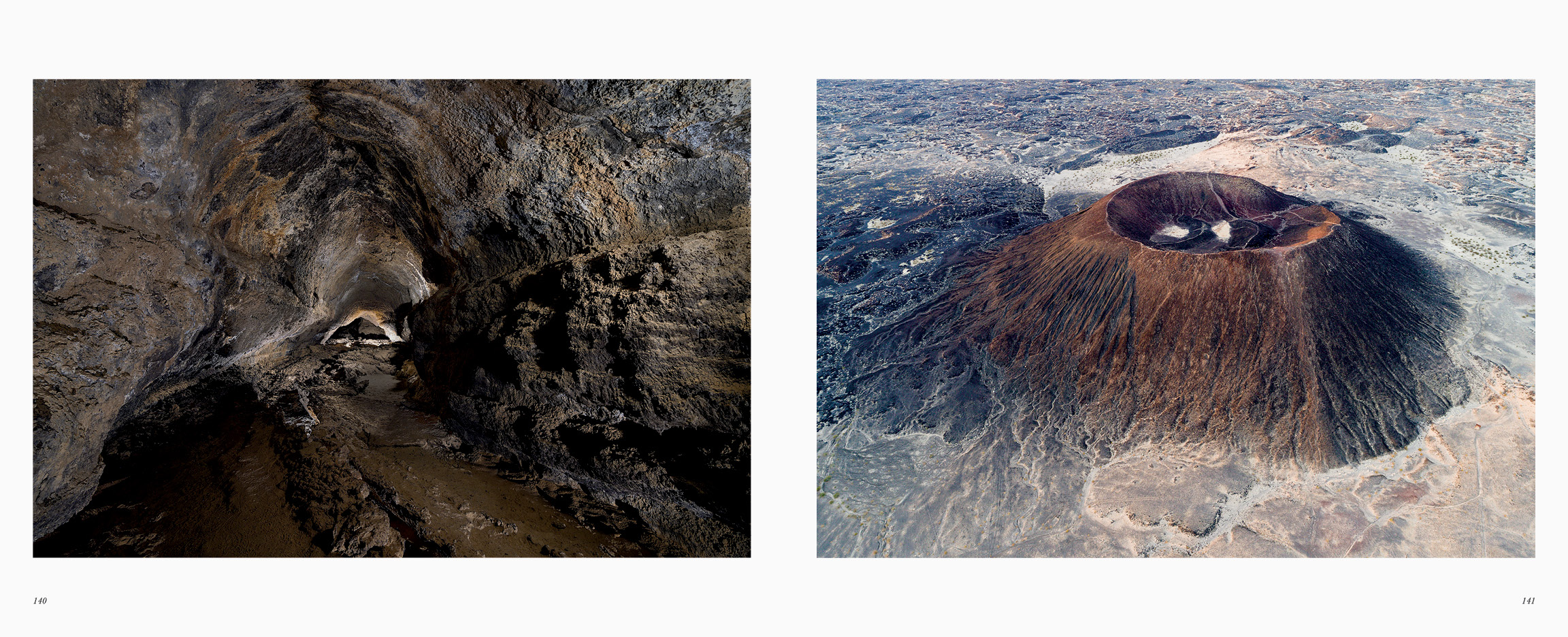

Feisol CT-3342, another series 2, 3-section tripod. It had three immediately appealing characteristics. It came with a center plate rather than a center column, could fold in reverse around a small ballhead (my choice was the Markins Q3i) for compactness, and at 1200 grams was lighter than both the Gitzo (1440 grams) and the Induro CLT 203. At first, I could see only one drawback besides the less solid build. The angle at which the legs spread was too small. I suppose the manufacturer designed it that way to claim a taller working height – an important consideration for a tripod without a center column. But that made the tripod less stable and more vibration prone than it would have been with a larger spread angle. In the field, another weakness proved more annoying. The tripod seemed to be more affected by grit getting into the lock systems than the two others. When I took it into water-filled slot canyons during my trips to Zion, I had to disassemble it and clean it several times a week to keep the legs operating smoothly enough.

During one of those canyon explorations, as I was swimming through a long watery passage, I flipped around to swim on my back – easier this way with a substantial backpack, and this keeps your hands out of the freezing water.

When I emerged from the water, I noticed that the Feisol was gone. It had fallen into the water from my backpack. Me and a companion returned into the water to try to fish it out, but the water was too murky, deep, and frigid. My tripods do not seem to like water! Although I think the Feisol would work fine in clean environments such as cities, for nature photography it was too sensitive to dirt. That’s unfortunate because there is still no lighter full-size tripod on the market. It is actually lighter than several of the “travel tripods” that do not even approach it in stability and usability.

I gave Induro another try. Although the performance in terms of rigidity to weight ratio isn’t the best, considering my tendency to lose tripods, it is a sensible choice at its reasonable price. I do not view it as the ultimate, high-end tripod, for which my search is still on as of this writing (maybe the subject of a future article?) but it has been working OK as my primary tripod. I appreciate that it requires less cleaning than the Gitzo, due to an improvement in the positioning of the washer that is compressed for locking the legs. Instead of floating, like in the Gitzos, it is directly fixed to the leg collars, making it a good obstacle to dirt. The legs do have a tendency to loosen at the apex, something that never happened with the earlier Gitzos even after years of use. However, this is quite workable since tightening the screws using the same hex key as the one for the quick-release plate fixes the problem for weeks.

Leofoto

Maybe because of aging, during my

long hikes, I did not feel like carrying the Induro and sometimes headed out without a tripod. This led me to look again for a lighter tripod. After extensive market research, I think the obscure

Leofoto LS-224C is the most lightweight, usable tripod, especially combined with its included ball head. The legs weigh only 725 grams, and the total weight with the ball head is 900 grams. For comparison, the Induro with the trusty

RRS BH-40 ball head is 2100 grams, while Gitzo with the Markins Qi3 is 1820 grams. The Leofoto is also an excellent value.

All the other tripods mentioned (besides the Gitzo series 1) extended more or less to eye level without center column (54″, 137cm), but the Leofoto LS-224C is quite a bit shorter (46″, 116cm). This can be excused because besides the comfort of not having to crouch, eye-level is rarely the most dynamic way to position a camera. Galen Rowell modified all his small Gitzo tripods by removing the center column and sawing off its locking mechanism. I think he would have been appalled by the much-hyped (and expensive at $600) Peak Design travel tripod that requires you to extend the center column every time.

On the other hand, he would have been pleased with the absence of a built-in center column on the Leofoto. Center columns can be helpful since they provide a significant height extension with little added weight. Leofoto offers an interesting solution in the form of a center column that screws into the tripod platform. It takes more time to install it than just extending it like with other tripods since you also need to unscrew the ball head. However, when you don’t need it, it doesn’t degrade the tripod’s stability, and of course, you can leave it home to save 105 grams. I only wished that, unlike the Feisol, they would have designed it with a wider leg spread angle. Nevertheless, the Leofoto is nowadays what I carry on backpacking trips or as a second tripod.

My current tripods:

Leofoto LS-224C,

Gitzo GT2531 with Markins Q-Ball Q3i,

Induro CLT-203 with RRS BH-40,

Gitzo 1325 (for sale, contact me if interested) with RRS BH-55.