National Park Bears

4 Comments

In Oh Ranger!, Horace Albright, the second National Park Service (NPS) director writes:

The bears are, without doubt, the greatest single attraction in the parks, at least from the visitor’s point of view.Maybe this is why a story about a woman facing charges over a bear encounter in Yellowstone National Park made it into national media headlines today. From reports, I understand that she got out of her car and stood on the edge of a parking lot when a mother grizzly and two cubs were closer than the park-mandated distance, then maybe didn’t retreat as they approached until a charge captured on video. After that video when viral, the National Park Service when as far as posting a “Wanted” notice on Facebook and Instagram:

On May 10, 2021 at approximately 4:45 PM, an unidentified woman approached a female grizzly bear and her two cubs at the north end of the Roaring Mountain parking lot. The female grizzly charged the woman who turned and walked away from the bears. The unidentified woman is described as white, mid 30’s, brown hair, and wearing black clothing. If you were around Roaring Mountain on May 10, 2021 at 4:45PM, or you have information that could help, please contact NPS Investigative Services Branch

Yellowstone National Park rules advise to:

Keep at least 100 yards (93 m) from bears at all times and never approach a bear to take a photoOne should always abide by rules, yet I wondered if at a time when parks are stressed by record visitation while facing understaffing and underfunding, vigorouly pursuing such violations are the best use of the service’s resources. Reading the unecessarily harsh comments, you get the impression that the woman’s actions were incredibly reckless and put her in an extremely dangerous situation. However such a bluff charge rarely results in a mauling (what to do during a bear attack, bear attack statistics). Looking at how attitudes over bears in national parks differ in other places and times provides some perspective.

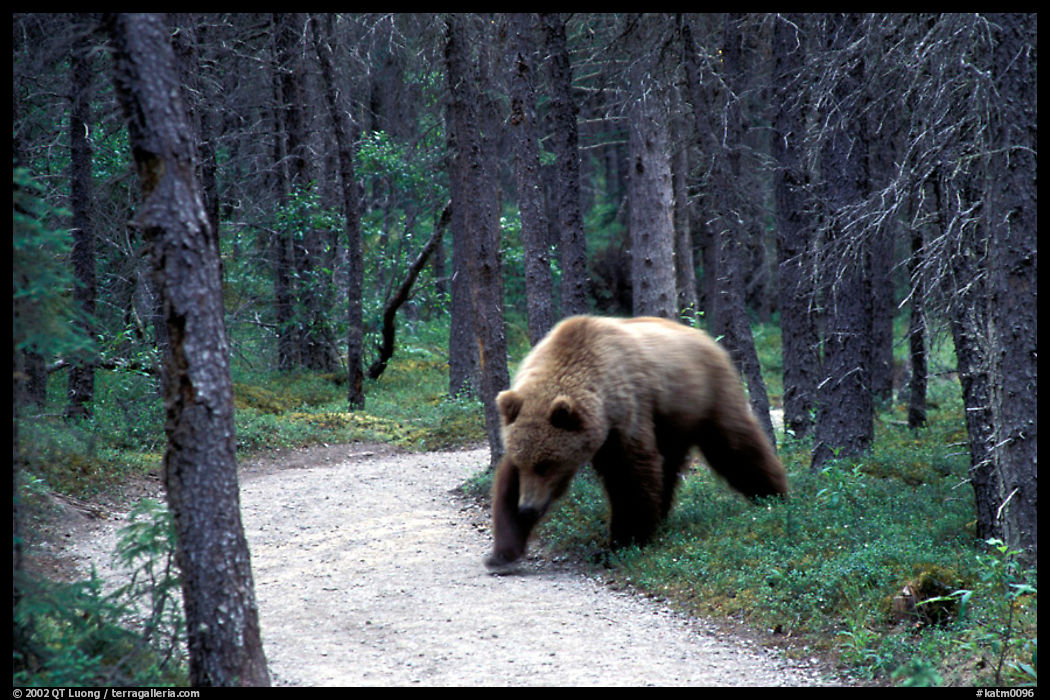

Katmai

When you think “bears in national parks”, the place that comes to mind is Katmai National Park. The park is largest bear protection area in the world and home to the highest concentration of brown bears, especially around Brooks Camp. It is routine there for people to come close to bears, and not only when they are on the viewing platform. When walking from the campground to the main viewing platform, in more than one occasion, a bear came out of nowhere from the dense forest and crossed the trail a short distance front of me. The first time, I thought about nothing else than trying to retreat slowly and keep my distance, but the second time, I had got used to the situation enough to snap a quick picture with the normal zoom on my camera – given that this was 2001, probably a 28-135mm.

The fellow paid me no attention. On that same trip, I would have an even closer encounter. The rules (misstated by Herzog in Grizzly Man) are:

1. Approaching a bear or any large mammal within 50 yards is prohibited.I interpret that to mean you can legally approach a bear up to 50 yards and then stay in place in some circumstances if the bear walks towards you. As I relate in this post about my second visit to Brooks Camp, bears do approach you, very close. Even though I had a camera in hand, I was too shaken to take a picture until he turned away. When the next day, I chatted about that experience of being followed and cornered by a bear, a ranger casually remarked with amusement “aren’t you glad that during the day we are here to direct your movements?”

2. Continuing to occupy a position within 50 yards of a bear that is using a concentrated food source, including, but not limited to, animal carcasses, spawning salmon, and other feeding areas is prohibited.

Bears in Katmai are coastal brown bears. They are the same genetic species as the grizzly bears living in Yellowstone and other interior areas, however the ecosystem aren’t similar, and the two have different temperaments. Coastal brown bears are tolerant of other bears and humans. The odd story of Tim Treadwell is told in at least two books and two movies. He literally lived and camped around bears for 13 summers before eventually running out of luck. Had he carried bear spray, he would have survived the rare predatory bear encounter that took his and his companion’s lives on the night before their departure. Besides a few infractions (such as not moving his camp around every five days, wildlife harassment, improper food storage), his stays were entirely legal. Interior grizzlies are more territorial and aggressive. Yet, the sort of close proximity that Treadwell had with bears was routine in the early years of Yellowstone National Park, as we’ll see next.

Yellowstone and Yosemite, early 20th century

Besides the National Parks Portfolio, my shelf also includes every book about the national parks published in the early 20th century. I enjoy reading them and observing the shifts in our thinking that occurred within a century. Most of the original editions can be obtained inexpensively if you search carefully.

The most entertaining of those books is Oh Ranger! (1928) whose quote opened this article. Unlike other books about the national parks, Oh Ranger! is mostly about people in the parks. One of the more striking shifts concerns the bears. Here is the start of the book’s first chapter:

“OH, Ranger, can I take your picture with a bear?”“Just a minute, ma’am, until I show this gentleman where to go fishing.”

“Where’s a bear, now?”

“Well ma’am, there was one in these woods an hour ago. Maybe we can find him.”

Five minutes devoted to the finding of a wild bear.

“Oh, Ranger, that’s a lovely bear! Stand closer to him, won’t you? Would you mind putting your arm around him? It would make a peachy picture. We’d just love it.”

“Sorry, ma’am, but it’s against regulations to hug the bears.”

“Oh, pshaw! Why do they have such foolish regulations? Well, just pretend to be feeding him something.”

Knowing the ways of bears, the ranger declined to “pretend.” He produced some molasses chews and actually tossed the food to the bear. It is dangerous business to try to fool a bear about food, and he should never be fed from the hand.

Click! Click! Click!

Another ranger was immortalized in picture, for the ninetieth time that day.

“It’s all in the day’s work,” explained the ranger.

The “dangerous business to try to fool a bear about food” is elaborated on in the third chapter entirely dedicated to bears:

“Fooling a bear” is something that just shouldn’t be done. To illustrate, there was a bear in Yellowstone known as Mrs. Murphy. There had been several complaints about Mrs. Murphy, who was accused of nipping visitors’ hands and feet, so a ranger was assigned to shadow her for a day and see what was happening. He reported as follows:One Sagebrusher, for the sake of a picture, held some bacon in his mouth and coaxed the bear to remove said bacon from his mouth. He got his picture and also escaped without injury. That Sagebrusher was lucky.

Another tried to make Mrs. Murphy jump for candy, like a dog. Now a full grown bear weighs about as much as a kitchen stove and is not built for jumping. So—Mrs. Murphy reached up, knocked the man’s hand down so that she could reach the candy. That frightened the tourist considerably, but he escaped without injury. He, too, was lucky.

A Dude, with no candy or food, held out his hand as though there were candy in it. Mrs. Murphy became annoyed at being spoofed and she nipped the man on the toe. He retaliated by kicking Mrs. Murphy on the nose, which is a bear’s most sensitive spot. She responded by whacking the Dude with her paw. He was bruised but not badly hurt. He was lucky.

Fully two score people fed Mrs. Murphy and her cub that day in the proper way, by throwing candy to her, and were entertained for hours by the bruins with no incidents nor accidents.

The only innocent visitor to suffer injury was a Dude who, disregarding a ranger’s warning, insisted upon walking between Mrs. Murphy and her cub, to take a snap shot of the cub. Apparently believing her cub in danger, Mrs. Murphy rushed the Dude, tore out the seat of his pants, and, as she thought, saved her cub. The Dude rode the rest of the day in a blanket to hide a certain blushing and over-exposed portion of his anatomy.

After receiving this report, the superintendent decided that Mrs. Murphy was no more guilty than the Dudes and Sagebrushers who attempted to fool her with food that did not exist.

That chapter (“Speaking of Bears”) is chock full of stories about interactions between visitors, rangers, and bears, each more hair-rising than another for a modern reader. In the book, Horace Albright, a key figure in NPS history, seems to condone visitors feeding the bears. Here is a picture of him (reproduced in the National Geographic’s centenial book of 1916: The National Parks: An Illustrated History) taken by the first official NPS photographer George Grant during Albright’s tenure as Yellowstone superintendent:

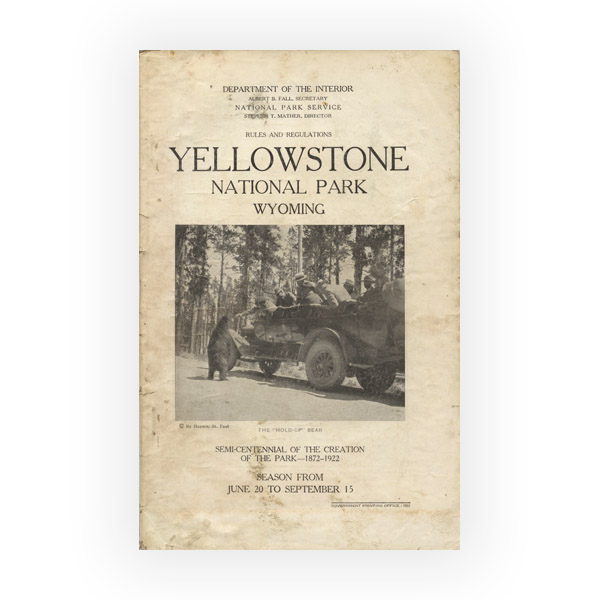

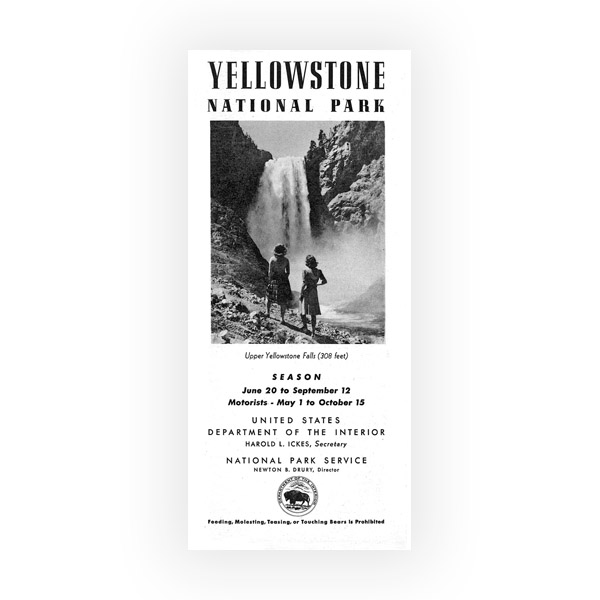

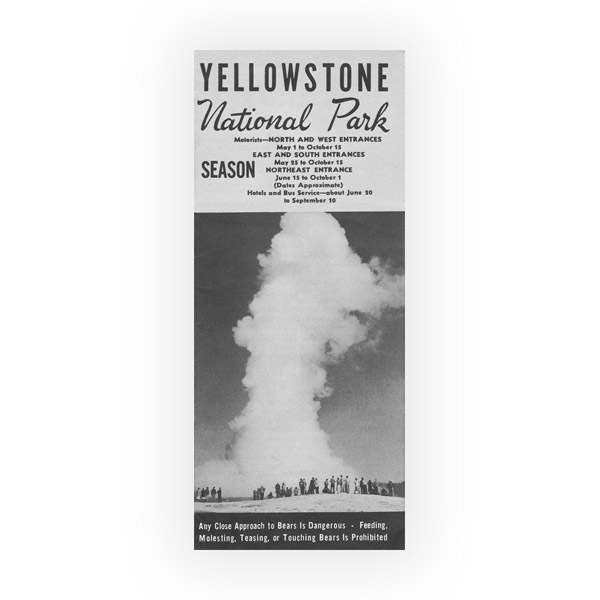

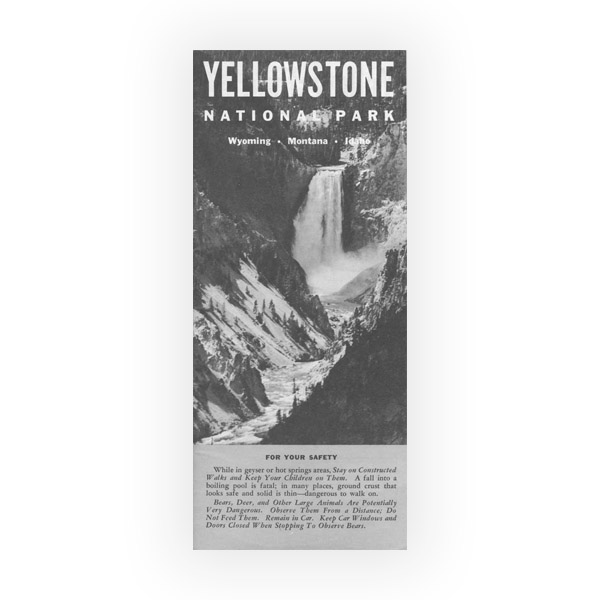

The cover of the official Yellowstone National Park visitor guide even shows a tourist getting a bear to stand on their hind legs by feeding them from an open-top automobile:

Curiously, the official NPS policy, for instance as stated inside the same visitor guide seems to be in contradiction:

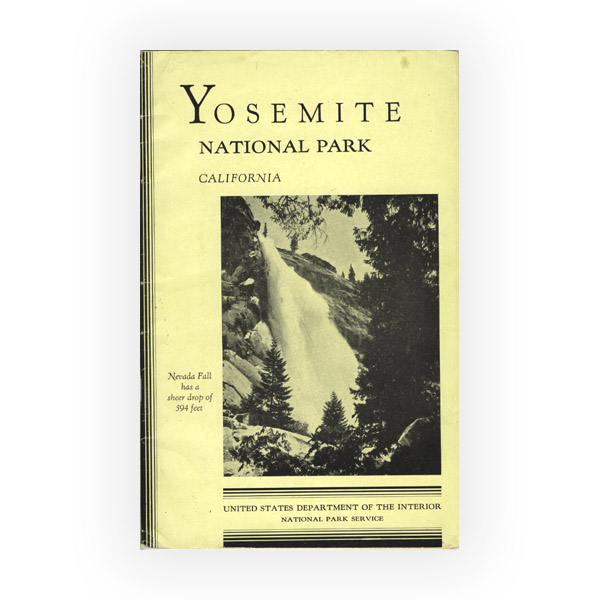

BEARS Even the big grizzlies, which are generally believed to be ferocious, are proved by our national parks’ experience to be inoffensive if not molested. […] It is contrary to the park regulations to molest or tease the bears. […] The brown, cinnamon, and black bears […] are playful, comparatively fearless, sometimes even friendly. They are greedy fellows, and steal camp supplies whenever they can. Visitors, however, should not feed the bears.Albright, in the same spirit as his mentor Mather, loved anything that brought publicity to the parks and knew that tourists loved bears. What the NPS objected to was not to feeding the bears, but to visitors feeding them for safety reasons – not out of concern for the bears. Unsurprisingly, visitors suffered dozens of bear-related injuries every year. The 1933 visitor guide to Yosemite National Park has this (emphasis added), which seems to corraborate the ranger’s method of bear feeding:

Warning about bears. Do not feed the bears from the hand; they are wild animals and may bite, strike, or scratch you. They will not harm you if not fed at close rangeIt is OK if the feeding is done by park staff, as explained in Oh Ranger:

In Yosemite National Park […] the feeding of the bears is made a great event. In the evening just after dark, Dudes, Sagebrushers gather on the slopes, across the river from the pits. All is quiet and dark. Suddenly the lights are flashed on, revealing the “salad bowl,” with any where from half a dozen to a score of bears growling and feeding as the bear man dumps numerous garbage cans of supper for them. A tree stump in the middle of the platform is painted with syrup each evening and there is great rivalry among the bears to get at this.The section “Education Service” of the 1933 visitor guide to Yosemite National Park indeed mentions on the summer schedule:

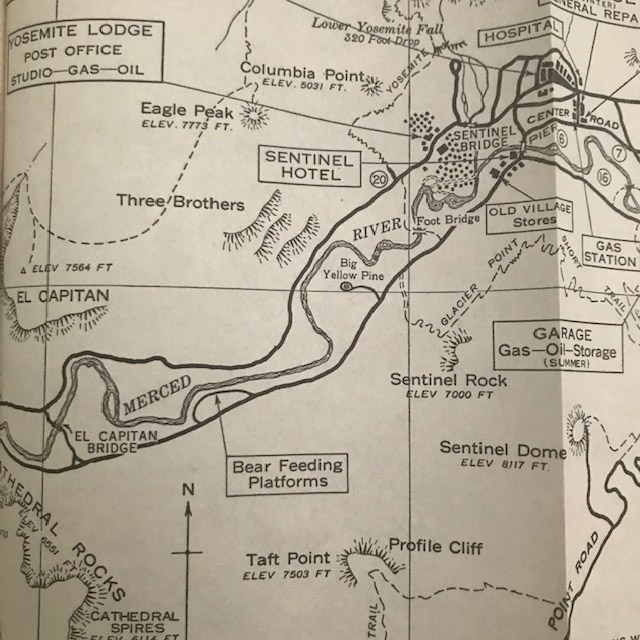

The bears are fed every evening at 9:30 at the bear pits, and a short talk is given on animal life in Yosemite.Every guide from 1932 to 1939 includes the same. It is unclear if this was left out from the 1940 guide because the practice was discontinued or because of the change in format of the guide. The new format accomodated less text, and the focus changed from rules and activities to a description of the park. The 1933 booklet includes two fold-out maps. The one of Yosemite Valley shows “Bear Feeding Platforms”:

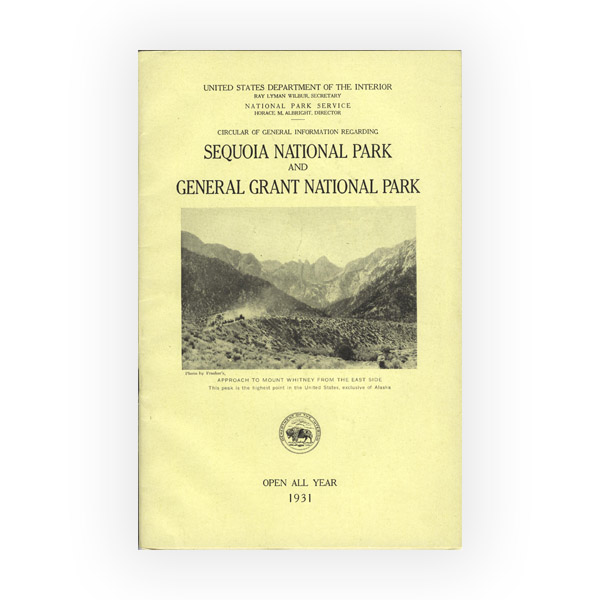

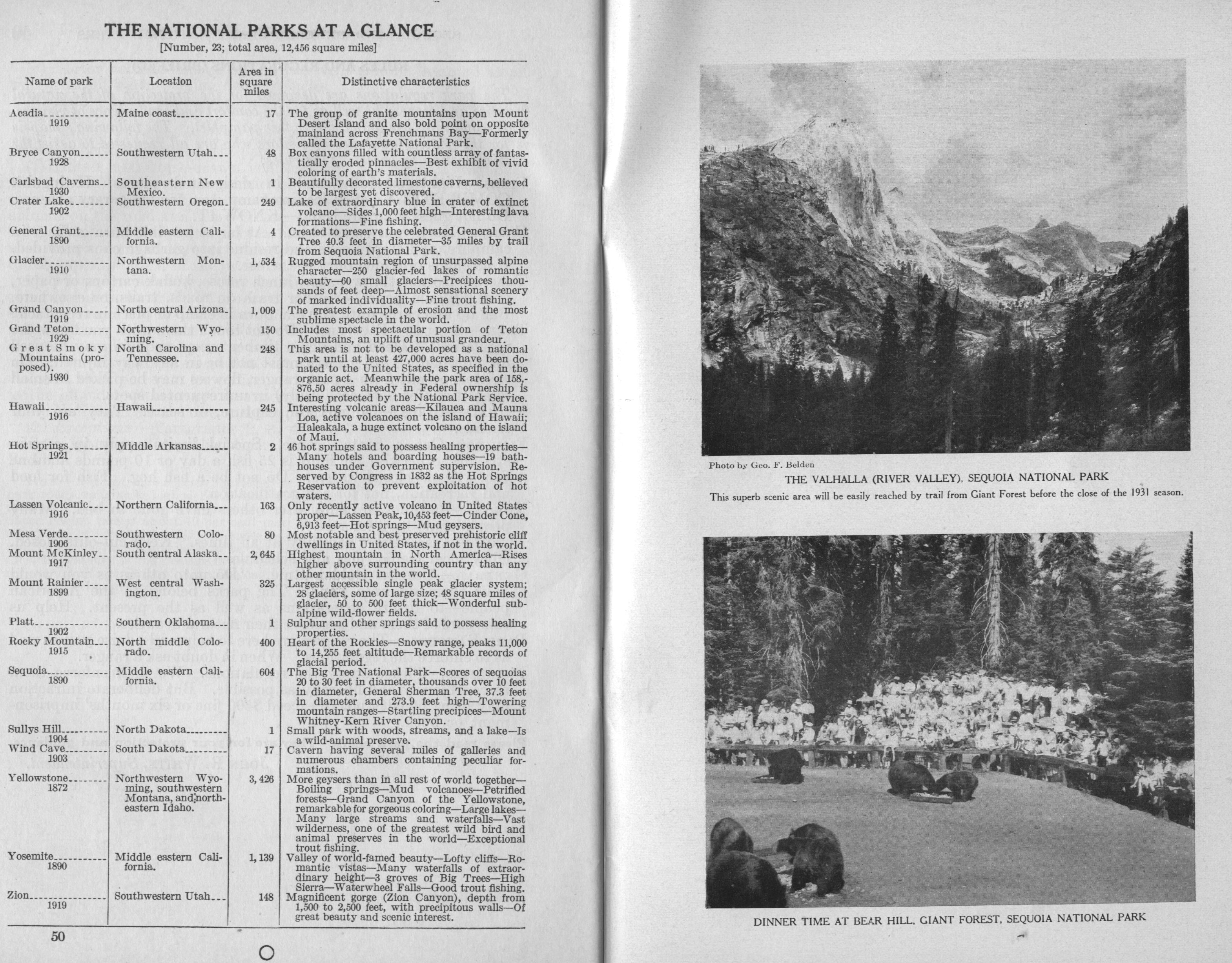

In addition, the 1931 visitor guide to Sequoia and General Grant National Parks indicates a similar practice:

OTHER ATTRACTIONSThe “Bear Pit” is the name give to the spot on the Circle Road at the garbage incinerator where many bears gather to feed on camp garbage. The best time to see them is from 5 to 7 p.m. when an attendant is on hand.

This is illustrated on the booklet’s last spread:

As its first wildlife biologist, George Melendez Wright initiated the entire scientific and natural resource management program of the NPS. His life was cut short by an automobile accident at just 31. Yet, during his brief career with the NPS, he lead the agency from a focus on the scenery and visitation to a focus on science and conservation with the realization that “our greatest national heritage is nature itself”. In 1932, Wright wrote of the Yellowstone bears:

Last summer for the first time two grizzly cubs became tame and were fed by hand around Old Faithful. This will not do and must be stopped before it is well started or the bear problem will be worse than ever. It takes time to teach the visitors to our national parks that they are the ones who are short-sighted in feeding candy to a bear. After all, the average citizen expects more intelligence from a bear than he, as an educated person, has any right to expect. He goes on the assumption that if he feeds a bear two sticks of candy and does not want to give it a third, he is the one to say, ‘No, no.’ And he believes that the bear is to be accused of an unforgivable breach of etiquette and lack of appreciation… if it takes all the candy out of his hand and takes the hand with it, perhaps.To learn more about George Melendez Wright, read this article from which the quote above originates. Among the many impactful changes he instigated was to phase out the feeding of bears for entertainment. The Yellowstone visitor guides of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s each feature on their cover a warning about bears that becomes increasingly strict. However, it was not until the 1970s that bear feeding ceased entirely in Yellowstone, when garbage dumps were shut down and now-ubiquitous bear-resistant trash containers installed. We have come a long way.

“…I wondered if at a time when parks are stressed by record visitation while facing understaffing and underfunding, vigorouly pursuing such violations are the best use of the service’s resources…”

In my opinion, when such pursuit results in national news stories about the two counts against her and, with luck, subsequent convictions, it’s an excellent use of NPS resources. At a minimum, there’s the potential to make many more tourists aware of how serious those things are. Even better, it might hinder that “record visitation,” reducing stress on the parks. We’re long past the point where our national parks need any promotion, and they would do quite well with fewer selfie-snapping wildlife disturbers. Yes, I know they’re not wilderness areas, but just as human overpopulation has wreaked havoc elsewhere it’s doing the same thing to national parks.

Maybe that is worth it to make a public example. I doubt that will have much influence on visitation, though. Crowding is really a problem in a limited number of areas that do not appear to include Yellowstone.

Crowding is a plenty big problem, even in Yellowstone:

https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/visitor-use-management.htm

It is all relative, I assume. I see almost daily updates from a local resident social media posts @Exotichikes, they do not depict an overcrowded park.