Return to JMT backpacking

4 Comments

This spring, I returned to an adjacent segment of the John Muir Trail, a quarter-century after my first visit. How did things change, particularly with respect to photography? Although I carried my 5×7 camera, my first backpacking trip about 25 years ago was mostly a fun outing with friends on a short section of the John Muir Trail (JMT). Since then, I’ve gone backpacking on more occasions as part of my project to photograph the national parks. Those trips weren’t mainly about walking and spending time in the wilderness, but rather about accessing and photographing destinations whose depth in the backcountry made them unpractical to reach during day trips. Having released Treasured Lands in 2016, the next year, when I climbed the Grand Teton, I did something that had become rare outside of family trips: embarking on an outing whose main purpose was not photography. I was looking forward to more of those mountaineering trips. However, the end of the year 2017 brought the reductions in size to Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. I needed to go back to work, starting a new place-based project centered on national monuments in early 2018. By June 2021, after six extremely busy months of writing and designing, I had finished the work on Our National Monuments, and it was time for a long-due vacation. Was there a better choice than the John Muir Trail?

After hiking the trail solo, my brother-in-law Nhon, wanting to share it with family members, offered to take them on the trail the previous year. However, his plan of 20-mile days turned out to be too ambitious for the others. The group bailed at Devils Postpile. After two weeks of rest, some of them went back to the trail, but beset by altitude sickness, blisters, stomach issues, and exhaustion, they exited early again. This year, the plan was to restart where they had left off at Kearsarge Pass. This was precisely a section of the trail I had not hiked at all before except for the descent from Mt Whitney to Trail Crest. With a more reasonable plan of 10-mile days, about 44 miles with 12,000 feet elevation gain in five days, with the promise to carry our food and collective gear (including a tent for comfort), I convinced my wife to join, although she had not gone on any backpacking trip since the birth of our children.

That southern section of the John Muir Trail is demanding. Between Kearsarge Pass and Trail Crest, it offers no escape routes. The trail’s altitude is consistently high to the point that another brother-in-law, Phuong, despite having hiked more than 600 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail to Kennedy Meadows in the weeks prior was still feeling the effects of altitude. Several sisters felt nauseated and could not eat enough. As the trail crosses the highest point of the entire Pacific Crest Trail at Forester Pass (13,153 ft, 4,009 m), hiking in early June, we were concerned about dangerous snow-covered sections. Fortunately, the snowpack this year was the lowest I have ever seen, and we breathed a big sigh of relief upon reaching the pass. Even though it turned out that the John Muir Trail is quite hard, a notion vividly conveyed in Ethan Gallogly’s The Trail.

JMT, Kings Canyon National Park

However, that fact facilitated my photography endeavors. On long-distance hikes, making fine photographs is a challenge for several reasons. Carrying photography gear is only one of them. All the others had switched to ultra-light gear. Not following the hiking scene, I was the only one using a traditional internal frame backpack from Dana Designs weighing more than 6 pounds empty, but I think it was necessary to carry my load. With the bear-resistant canister, tent, and sleeping bag, my backpack was full, although I had kept the photography gear to almost a minimum. I had brought one Sony A7R4, 24-105mm f/4 and 12-24mm f/2.8 lenses, and the Leofoto small LS-224C tripod (described here), the later mostly for night photography and timelapses. Accessories were limited to half-a-dozen batteries and a polarizing filter. Compared to the 70 lbs backpacks I carried at a younger age, the 40-50 lbs weight seemed reasonable, yet compared to other family members, it was towering high, and each time I stopped, I could not wait to take it off my back. As I aged, I was definitively grateful that equipment has become much lighter for somewhat comparable image quality.

Even if you were to photograph with a phone, you’d still be subject to the main challenge, which is timing. You are rarely at the right time with the most favorable light since the need to progress dictates your schedule. The time to photograph with the least constraints is in the evening, but since each day we woke up before dawn to make an early start, on those long summer days evening photography ate up precious sleep time. We were a group of seven. When you hike with a group, you don’t want to make others wait for you. But when you stop to photograph while hiking, within just a few minutes, the group has moved surprisingly far from you. On that trip, I was able to cope with this situation only because of the fitness I maintain – those runs every other day when at home paid off. Usually, I carried the camera around my neck with a Photoflex Galen Rowell-branded waist camera pouch (long discontinued) to distribute its weight and prevent it from bouncing, making access quick. The other lens stayed on the top of the backpack in a pouch. On sections of trail where I did not expect photographing, I also stuck the camera, in its pouch, on top of the backpack. During the day, I handheld all the photographs. This was possible because of image stabilization since stopping down and using a polarizer eat shutter speeds. My wife and I trailed the group, and after stopping to photograph, I was able to catch up with her within minutes. Still, I had to find compositions quickly.

I made about 900 exposures. In the end, except for the sore shoulders, I felt that photography didn’t detract from my experience in the wilderness, but that the additional challenge made it more interesting and alleviated the unnatural pace of hiking with others. Having spent recent years in more arid and lower-elevation lands, I had somehow forgotten how beautiful the High Sierra was. The photographs are far from conveying the entire experience, which is also made stronger by the effort and difficult times. Yet, they can serve to awaken memories not depicted, and that’s why we cherish them.

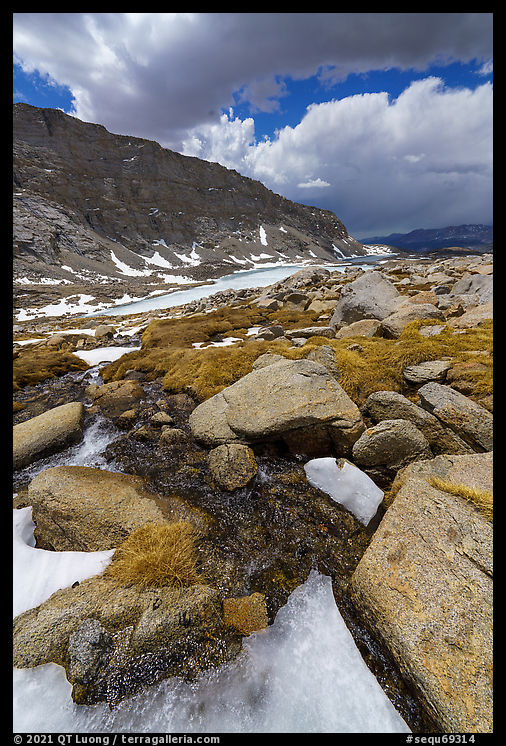

JMT, Sequoia National Park

I am amazed at your hiking abilities and still able to stop and take high quality pictures! You are Superman in my book! Kudos!

Thank you Karl. I work hard on those trips – and at home to stay in good shape.

Loved this writeup and understand well the evolution of cameras as we get older or change what value / need. This brought back lots of memories. EXCEPTIONAL images given the challenges of the trip, I am very impressed. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten more into ultra light gear and my current camera is now a Sony RX-100 VI. Am thinking about a Z50 camera with small lens for future trips that are shorter. Thanks again for recounting your adventure, thoughts, and images.

Thanks Paul. I have the original RX-100, but so far haven’t had to use it as my main camera. The focal range in the newer versions and other features are impressive. Regarding ultra-light gear, the comparison between the two following photos 25 years apart at Kearsarge Pass is instructive. My sister-in-law (in the picture) just bought a 2-person tent that weighs 23 oz.