Philip Hyde books

11 Comments

After Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, the third pillar of conservation photography in the 20th century was Philip Hyde (1921-2006). In fact, it can be argued that Philip Hyde was more instrumental in this role than his two more famous counterparts, and that it was precisely for that reason that he is less known. A quiet and humble giant, living a simple life out of the spotlight, he always felt that his own art was secondary to nature’s beauty and fragility, to the environmental campaigns he participated in – more numerous and successful than any other photographer. As an artist, this belief was reflected in his direct style, which appears deceptively descriptive, favoring truthfulness and understatement rather than dramatization, but upon closer examination represents a uniquely personal approach to landscape photography. Today it may be easy to take his compositions for granted, but that’s mostly because they have been emulated countless times. The work was pioneering. William Neil writes in a penetrating tribute: “I have little doubt that every published nature photographer of my generation has been inspired by Philip’s efforts”. I must confess that I discovered the work of Philip Hyde past my formative years. However, I actually find more common ground with him than with the other large format masters. Studying his work has confirmed my choices to photograph also in ordinary light, without radical angles or over-manipulation, and generally to try to show what is there, rather than what I want the viewer to see.

The essay linked above is part of a blog created by David Leland Hyde, Philip’s only son, who is doing a great job to keep alive his legacy. Together with philiphyde.com where portfolios are presented, it is the best resource to learn more about Philip Hyde’s art, life and times. I am grateful to David for suggestions in preparing this article. Here is a short video about Philip, narrated by David:

Although Philip Hyde was an excellent printer who had learned from the very best and was often approached and shown by the finest institutions, because of his focus on conservation, he rarely sought to exhibit his work, instead contributing images for publications that were likely to reach influencers as well as masses. The photography book was therefore his natural medium. By David’s count, Philip Hyde was a primary photographer for at least thirty books. Since none of them are retrospectives, a publication which is certainly long overdue, there is virtually no overlap: each book brings only new images, instead of a rehash of “hits”. Many of them have been reprinted several times, however none of Philip Hyde’s books are currently in print. This is not an impediment since almost all of them can easily be purchased in used bookstores, often for an incredibly low price. I am discussing below all the Philip Hyde books that I own, presented in chronological order of publication.

This is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers

This is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers

This book broke new grounds on several accounts. Prepared to advocate against the proposed Echo Park and Split Mountain dams in Dinosaur National Monument, it is possibly the first conservation photography book ever published. Philip Hyde, who just recently graduated from the California School of Fine Arts, studying under Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and other luminaries, was a young and motivated photographer ready to go to work on short notice, for little money. He was sent on the first conservation-oriented freelance assignment (expenses paid plus $1 per photo published – equivalent to $9 in 2013 !) by the Sierra Club. Although Dinosaur National Monument had expended to over 200,000 acres, few Americans knew anything about it, so the challenge was to inform about what would be lost. Read more about this pioneering campaign – which began the transformation of the Sierra Club into a national organization – and Philip Hyde’s role in it in David Leland Hyde’s 9-part account: The Battle Over Dinosaur: Birth of Modern Environmentalism. The book, published in 1955 (reprinted in 1985) is more notable for its historic importance than as a photography book. It opens with a 36-page picture section consisting of images and extended captions, of which 17 (in B&W) are from Philip Hyde. This is followed by the main section (96 pages) consisting of seven essays by different writers. Because images and text were contributed by many, only the editor, Wallace Stegner, who also wrote the first essay, is listed on the title page.

Island In Time: The Point Reyes Peninsula

Island In Time: The Point Reyes Peninsula

The first title on which Philip Hyde is listed as a co-author, this was published in 1962, the same year the Sierra Club published “In Wildness Is The Preservation Of The World”. The difference of approaches is telling. While the later was a well-planned art project, on which Porter had been working since the 40s, Island In Time was a much less expensive book expressly published to save Point Reyes from development. It was quickly put together to assist fundraising efforts to buy the ranches of Point Reyes before developers bought the land to build homes, an urgency typical of the books in which Philip Hyde contributed. Although the text, which aims to introduce and describe the Peninsula to the general public, is the most extensive part of the book, it incorporates a number of plate sections, mostly black and white, but also some color. This mix is unusual for most photographers, but Philip Hyde was early on proficient in both media, able to print silver gelatin, dye transfer, and Cibachrome. He would gravitate to color in his later years describing how it fits better his goals “Black-and-white lends itself to manipulation that can dramatize a subject. Color tends to record what is seen, so it is no coincidence that I use color for that purpose. I don’t feel nature needs to be dramatized: it is dramatic enough!”.

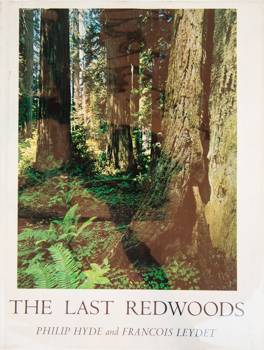

The first book of Philip Hyde in the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series (1963) was co-authored with nature writer Francois Leydet, whose text emphasizes not only the beauty of the ancient trees, but also the threats to them. It was part of a campaign that helped establish Redwood National Park. Except for 8 color pages, the photographs are in black and white (a few are from Ansel Adams and others). Besides nature images of pristine redwood forests, we also see depictions of forestry operations and devastating clear cuts which anticipate photographs by Robert Adams of the same subjects in the Northwest. The Sierra Club Exhibit Format publishing program created the first coffee-table nature photography books: volumes of unprecedented quality, in a large (10 x 13) size that David Brower thought necessary to immerse the viewer into the photographs, therefore maximizing their impact to argue the cause of conservation. The series brought Sierra Club national recognition, while helping to establish landscape photography as a popular art form. Ansel Adams role was prominent in the first volumes, but he disengaged himself after the books turned to color photography. Eliot Porter authored more Exhibit Format titles, but Philip Hyde was the workhorse, providing images for nearly every environmental battle of the Sierra Club in the 1960s and 1970s. Read more about the series and Philip Hyde’s role in it in David Leland Hyde’s account: Sierra Club Books: Exhibit Format Series.

Time and The River Flowing: Grand Canyon

Time and The River Flowing: Grand Canyon

Francois Leydet investigates and reports on the significance of a living river, in support of a multi-faceted campaign to prevent dams to be built within the Grand Canyon. The book (1964), famous for being an important tool in saving the Grand Canyon, is illustrated by color photographs from many photographers – some of them reproduced small and combined on a page, as the priority is given to the story. Philip Hyde had more images than any other photographer in the book (Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Martin Litton, Clyde Childress, Richard Norgaard, P. T. Reilly, Joseph Wood Krutch, Katie Lee and others), and would go on to contribute to five books about the Colorado River: The Grand Colorado (1969), Glen Canyon Before Lake Powell (1970), The Wilderness World of the Grand Canyon (1971), Glen Canyon Portfolio (1979), Ghosts of Glen Canyon (2009). Part of the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series.

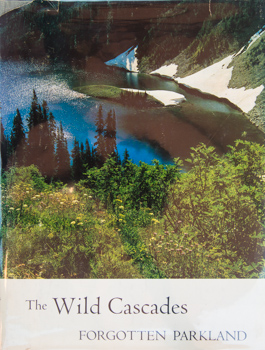

The Wild Cascades: Forgotten Parkland

The Wild Cascades: Forgotten Parkland

Harvey Manning (editor of Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills) makes the case for the establishment of North Cascades National Park, in a format similar to the previous book, except for the fact that he combined poetry by Theodore Roethke with photographs. Both black and white and color (16 pages), they are from a number of photographers (including Ansel Adams, Martin Litton, Bob and Ira Spring, David Simmons, John Warth). Part of the Sierra Club Exhibit Format (1965). Like the three previous books, it is historically significant. Unlike Adams and Porter who put much emphasis on establishing themselves as artists, Philip Hyde’s focus was in conservation, and at this point in his career, he viewed himself mostly as Sierra Club team player, therefore contributing to books without seeking cover credits. From my exchanges with David Leland Hyde, I got the impression that Philip Hyde was exactly the opposite of a credit-seeker, which certainly contributed to his relative lack of renown compared to some contemporaries.

The Big Sur coast is celebrated by paragraphs of poetry from Robinson Jeffers, interspersed with photographs generously reproduced in a clean design, both in color and black and white. Unlike the three previous books, photography is given the primary role, resulting in a more beautiful book. The list of the other contributing photographers reads like a who’s who of West Coast photography: Ansel Adams, Morley Baer, Wynn Bullock, William Garnett, Eliot Porter, Cole & Edward Weston, Don Worth, Cedric Wright… Part of the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series (1965).

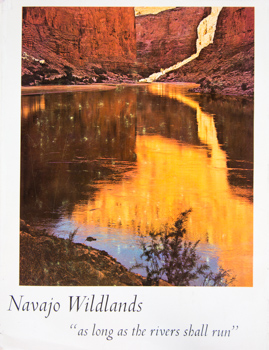

Navajo Wildlands: As Long as the Rivers Shall Run

Navajo Wildlands: As Long as the Rivers Shall Run

The second book of Philip Hyde in the Sierra Club Exhibit Format Series (1967) was co-authored with notable archaeologist Stephen Jett who appraises the great scenic resource of the Navajo country and the understanding of the native inhabitants towards the land. Unlike the previous ones, this book uses exclusively images from Philip Hyde. While he continued until at least the 70s to do black and white photography on the West Coast and Sierra Nevada, Philip Hyde felt early that color was better at depicting the Southwest, his other stomping grounds. All photographs for this book are in color, and reproduced large with a clean design which gives them prominence on the page. Because of the design, excellent selection of quietly luminous images, and evocative nature of the book (as opposed to the “activist” volumes – although it should be noted that Navajo Wildlands was part of the inspiration for the establishment of many Navajo Tribal Parks), reinforced by the spiritual focus of the text, I feel that this is the most beautiful of Philip Hyde’s numerous books about the Southwest that I’ve seen.

Maybe deservedly the most well-known book of Philip Hyde, because of the complementarity of his color photography with text by the celebrated desert writer Edward Abbey. In a beautifully written, and informative text, they both evoke the canyon country of Southeast Utah, gently advocating for protection of the Escalante Canyons, extension of Capitol Reef National Monument (to include southern parts of the Waterpocket Fold) and Canyonlands National Park (to include the Maze District) – all goals that were subsequently met at one point in time. Travel to some of those areas remain difficult in 2013, so think about the sense of exploration and discovery that those hardy wilderness travelers must have been felt in 1971. The first part of the book, sparsely illustrated, is written by Abbey. The second part consists of three portfolios with full-page reproductions (some maybe a bit too contrasty) each excellently introduced by Philip Hyde himself, whose voice begins to be heard in his books. Although it was not officially part of the Exhibit Format Series which at this point had been stopped, it was published by the Sierra Club with the same presentation as those books, making it a beautiful volume.

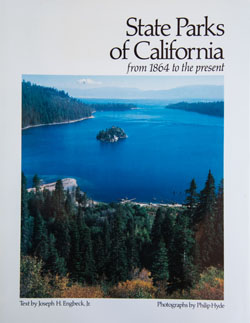

State Parks Of California: from 1864 to the present

State Parks Of California: from 1864 to the present

Philip Hyde contributed to nearly 80 books, so some are bound to be photographically less interesting. I’m mentionning this one as an example, since it is on my bookshelf. Philip Hyde’s contribution to this book (1980) is similar to mine to The National Parks: America’s Best Idea: he provided all the contemporary landscape photographs, but the bulk of the book’s illustrations consists of black and white historical photographs originating from various archives. Those books are also similar in the preponderance of the text, which reminds us of how hard early conservationists had to work to establish the parks.

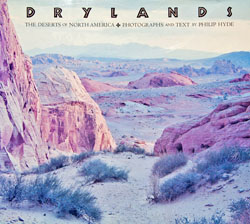

Drylands: The deserts of North America

Drylands: The deserts of North America

Put together by the packager of several Galen Rowell books, this is the most sumptuously produced book (1987) by Philip Hyde, with a large 13×15 horizontal trim, the largest number of pages of any of his books, and modern color reproductions – don’t judge them by my copy’s cover, it was discolored by sun exposure. The scope is also his most ambitious, since not only his photographs cover all the five North American Deserts in the US and Mexico, but Philip Hyde also wrote most of the text, which includes descriptions of the areas and reminiscences of his own travels. The introduction and naturalist’s notes are by best-selling and prize-winning nature writer David Rains Wallace. This is a remarkable production, the culmination of his years working in the Southwest, possibly his most important book. Maybe it’s just me, but although I like the educational aspect, I have mixed feelings about the focus on geography and its resulting design with maps and drawings of plants and animals, and also the colored borders around images and full bleeds. For some reason that I cannot exactly pinpoint, although technically much better reproduced, many images in this book feel to me more descriptive than those in the two previously mentioned Southwest books, esp. Navajo Wildlands. That’s not the case of all of them, of course, an example being the superb “Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Idaho”.

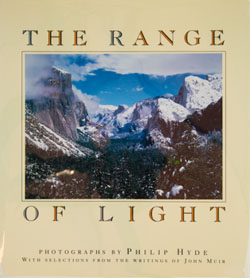

The last book (1992) by Philip Hyde, about the Sierra Nevada close to his home, is also his most personal. It consists of three parts. The first one shows black and white photographs paired on the same page with a quotation from John Muir selected by Philip Hyde – a concept similar to the one used by Porter in his first book. The second one continues the same format, but using color photographs. The co-existence of both portfolios is an impressive achievement. The last part is an autobiographical essay in which he reflects on his life as a photographer, evoking Sierra Nevada trips, and friendships with his noted West Coast photographers peers, and his personal philosophy. Philip Hyde was generally a quiet giant, a self-effacing man, so I am glad that at least he has chosen to give us a glimpse of his life and thoughts. Because of the printing quality of the book, the control he had over its contents, and the window its offers into several aspects of Philip Hyde’s art, this would be my first recommendation for an introduction to his work. Complement it with at least one of the three latter Southwest books I listed (Navajo Wildlands, Slickrock, Drylands).

Were you aware of all this work ? Did you have any of those books ? Did they influence you ?

Part 4 of 5: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

Excellent QT. Love this post for giving Philip Hyde his due. I personally own Drylands and the Pt. Reyes book myself. Both are full of excellent work, but most importantly, historically significant.

Thank you, QT, for the great write-up, the links and the small corrections. It is overall amazing how accurate you are on your facts. I admire the way you make a serious study of each of a number of significant landscape photographers. Have greatly enjoyed your book write-ups on the big three pioneers of conservation photography, Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter and Philip Hyde. Maybe you ought to run with this…? Would love to see a piece on Edward Weston books, Minor White, Paul Strand, others. Do you have many of these photographer’s books?

QT, such a fantastic write-up. Thanks for making this effort…I learned a bunch and subsequent to reading the post, found a copy if “Wild Cascades” — very excited to see the North Cascades (my backyard) through Philip Hyde’s eyes.

David, thanks for kind comments and help. Thanks also Richard and Wesley. I plan only one more post in this series, I’ll let you guess the photographer ! It’s unlikely I’d write about the 3 you mentioned, I do have a few books of each, however not enough to account for their work.

An absolutely inspiring write up on an absolutely inspirational photographer. I did not have the opportunity to meet Philip Hyde, but as a friend of David Hyde I feel completely connected to his work & the stories & passion behind his photography. Really beautiful stuff.

I’ll take a guess and say Galen Rowell is the next photographer you will profile. 🙂

Phil Hyde’s ego was small, but his images are absolutely seminal and stunningly beautiful and big in the grandest way. He is the gold standard for landscape photographers of the baby boom generation in so many ways. First, looking at Phil’s work was the only way to learn how to become a nature and landscape photographer. Each of his books was a post-graduate course in lighting, color, composition and technique. This information could be found no where else. I remember when I bought my first 4×5 in 1976 and had no idea how to use it. Amazingly Desert Magazine (remember that!?) was holding a workshop with Phil in ZIon National Park. I immediately signed up, paid my money and took time off from my English teaching job. As it grew closer, my excitement grew to a fever pitch. Phil Hyde was going to help me figure out a 4×5! Imagine my sadness (I almost cry now) when it was cancelled due to lack of sign-ups. It set me back years. I have a copy of Slickrock signed by Ed and Phil. It’s my most prized possession. I will raise a toast to Phil tonight after the march here in Moab to create a Greater Canyonlands National Monument. HIs legacy lives on–photographers providing their images to preserve and protect the wild landscapes they love.

Tom, thanks for sharing your perspective and memories. Nowadays there is so much information and images available that it’s easy to forget it wasn’t always the case.

A fitting and very much deserved tribute, QT. While there is no disputing the contribution made by Adams and Porter to the art of photography and to its use in conservation campaigns, I think Hyde truly deserves the distinction of being the first true Conservation Photographer. There are many reasons and ways to practice photography but every one of these books speaks to Hyde’s work and, indeed, life, being about the great love of, and reverence for, the American landscape. Thanks to the work of people like Hyde (and David Brower) we are all better off today than we would have been if they had not pursued their mission with such passion and dedication. We owe them a great debt of gratitude.

This is a wonderful write-up, QT, and it made me pull my own copy of Slickrock off the shelf to re-read it. I second the other commenters in saying that Philip Hyde was instrumental in making landscape photography what it is today, and in giving us places to do landscape photography.

I hope you continue with the series. I gained a lot from it, though probably the most from the first about Ansel. Your review/discussion of his critical reception made me realize for the first time the common thread between all of these photographers: they were photographing subjects that they cared deeply about, without cynicism or ironic distance. The cool or detached viewpoint simply isn’t them. Personally, I think it’s much easier and safer to maintain a diffident or aloof and cool distance. Loving something, and showing that explicitly and publicly, takes an unusual courage, and these photographers all had that.

Thanks again.