The Living Colorado: Photographing the Grand Canyon from the River

One Comment

http://www.terragalleria.com/blog/the-living-colorado-photographing-the-grand-canyon-from-the-river/

The Colorado River is the main waterway of the American Southwest. Over millions of years, it has carved the Grand Canyon, the most spectacular intersection of water and stone, time and motion. The Grand Canyon segment of the Colorado is not only its most dramatic stretch but also the longest and wildest continuous white-water route in North America.

A journey down this river is both intimate and monumental. When you step into side canyons — as explored in the previous post — you find sheltered grottos, delicate gardens, and sculpted narrows. But from the main channel, you perceive the canyon as a single, unified force: a vast cathedral of rock, rising in near-vertical walls that soar 5,000 feet above. The river at your feet feels alive, breathing and shifting beneath you, oscillating between languid stretches and explosive rapids. This is not merely a passage through a canyon; it is a passage into the deep memory of the land, where each bend and each rapid holds a fragment of geologic and human history.

A rapid is a section of river where the water surface becomes turbulent due to a sudden increase in gradient, flow constriction, or the presence of obstacles like rocks or ledges. Rapids are among the most vivid evidence that a river is alive. Before Glen Canyon Dam, each major flood reworked the canyon’s entire rapid system. The river flow was wild and unpredictable, shaped by natural cycles. Now, controlled flows have sharply reduced flood peaks, and daily releases often fluctuate for power generation. The rapids persist but have become more fixed. Between Lees Ferry (mile 0) and Diamond Creek (mile 225), there are approximately 160 named rapids, with a dozen considered Class V.

The international scale of river difficulty rates rapids from Class I to Class VI based on technical complexity, risk, and rescue difficulty. Class I rapids are easy while Class VI is considered unrunnable. If a Class VI rapid is consistently navigated without catastrophic outcomes, it is reclassified as Class V. The scale is exponential — each step up reflects a significant increase in difficulty — and can vary with water levels. Unlike ocean waves born of wind and distance, which travel, rapid waves stand still, shaped by rock and collision — fluid yet fixed, chaos anchored in place. In the biggest rapids of the Grand Canyon, standing waves can reach 10 to 20 feet in height, depending on flow conditions.

As I expected, our large motorized raft was more stable than the oar raft I rode a decade ago. Light and responsive, the smaller watercrafts are lifted by waves. This results in considerable vertical motion that can be dangerous if one is not careful, as I unfortunately learned by experience. But what I didn’t expect is that while the weight and speed of the larger motorized raft help them plow smoothly through waves rather than riding them, this often sends walls of water crashing directly over the bow. Compounding this effect, guides often aim directly into waves rather than trying to avoid the biggest hits. In addition, AZRA’s particular seating arrangement calls for passengers to lower and wedge themselves between the gear boxes during the largest rapids. While this eliminates any risk of passenger accident, the lower position makes you even more exposed to water onslaught.

The motorized rafts are about 35 feet in length. How wet you get depends largely on where you sit. At the rear, it’s mostly splash, comparable to what you’d experience at an amusement park water ride. In the front, you get soaking wet. On the first day, I found myself sitting in the front because I was one of the last to embark. Sitting at the front offers the best photographic opportunities, since your view ahead is entirely unobstructed. On the second day, I offered to switch seats with other participants, but seeing how wet I got — and on a first day that didn’t feature big rapids — nobody took me up on the offer, so I ended up sitting at the front for the rest of the trip.

Since this is a river trip, maybe one should expect to get wet. The reason that is consequential is that the Colorado’s water is surprisingly cold year-round, regardless of season and air temperature. This is because it is fed from the bottom of Lake Powell via the Glen Canyon Dam. At the start, that temperature is a bone-chilling 45°F. Absorbing solar radiation and mixing with warmer side streams, it reaches about 50°F at Phantom Ranch, midway the trip, and then 60°F at Lake Mead.

Even on a warm day, once you are soaked in water that cold, it can take a while to warm up, as all your layers remain wet. On the day we tackled the big rapids of the Upper Granite Gorge in cloudy weather, I was barely able to keep warm despite wearing one of the heaviest fleece jackets underneath a mountaineering-grade shell. Unlike paddle vests that have rubber seals, that top-of-the line jacket was not sealed at the wrists and neck. The massive sheets of water from the larger rapids send water through those openings that end up soaking everything. Even though wearing thermal long-sleeve underwear tops (synthetic, as cotton is very slow drying) may sound overkill in May, those were essential to stay warm while being constantly drenched. Seeing how pale I looked after disembarking, my friend Régis urged me to go change quickly into dry clothes instead of joining in the human chain helping unload the raft.

There is not an instant of boredom on the river. I kept my river guidebok within reach, hoping to read between rapids — but the canyon never allowed it. Every moment demanded attention, demanded presence. Every bend hides a new surprise: sometimes it’s the way light ignites a wall into glowing amber or carves deep shadows into mysterious depths; other times it’s a sudden shift in water color, a hidden eddy, or a new rock face emerging. The interplay of light, water, and geology transforms each stretch into a unique, fleeting world. No two river bends are ever the same — each moment feels like a discovery.

Photographing from the raft reminded me of aerial photography, where you are also operating from a moving platform. Besides the technical necessities such as a high shutter speed, the challenge is to anticipate compositions. On a charter flight it may be possible to ask the pilot to fly back, but on the river, there is mostly no going upstream. While the position of the canyon walls does not change rapidly as you float, the foreground elements do. Those include the river itself, and it is the prominent presence of the river that distinguishes landscape images made from the raft from those taken from the shore. Those photos are more challenging to make, but they capture the essence of a river trip and cannot be made from land.

Given what happened ten years ago, this time I did not plan to photograph during the rapids and therefore did not bring an amphibious camera system. Influenced by the images of dories — small, lightweight wooden boats pioneered by Martin Litton that dance dramatically through rapids — in The Hidden Canyon (1977), John Blaustein’s book with text by Edward Abbey, I also assumed that a motorized pontoon raft would not provide enough excitement in the rapids to justify the risk. However, after seeing how safe AZRA’s seating arrangements were — and the amount of water coming directly at us during the rapids — I tried to capture splashes with my antiquated phone, which as the only waterproof camera I had brought, was still better than nothing.

Wanting to photograph every moment until the last possible instant before rapids up to medium size, I would hurry to stow my main camera safely just before the raft hit the waves. It’s a nervy way of working — trying to hold on for as long as possible while making sure the camera isn’t exposed when a crashing surge arrives. On smaller rapids, your body can act as a shield; on bigger ones, you need to stow the camera in a waterproof enclosure. Although a Pelican case closes quickly, its weight and hard sides make it a hazard if not properly secured. The waterproof Lowepro DryZone bags can sit on your knees, but their drysuit-style zippers are hard to operate quickly enough. This leaves a small dry bag as the most practical option. The outfitter-provided day-use dry bag (18″ wide × 24″ long, 30 liters) is adequate. There’s always a trade-off between access and protection — on occasion I’ve stowed two cameras in it, although that is far from ideal. I’d rather risk a scratch or two on the cameras than potentially miss a moment.

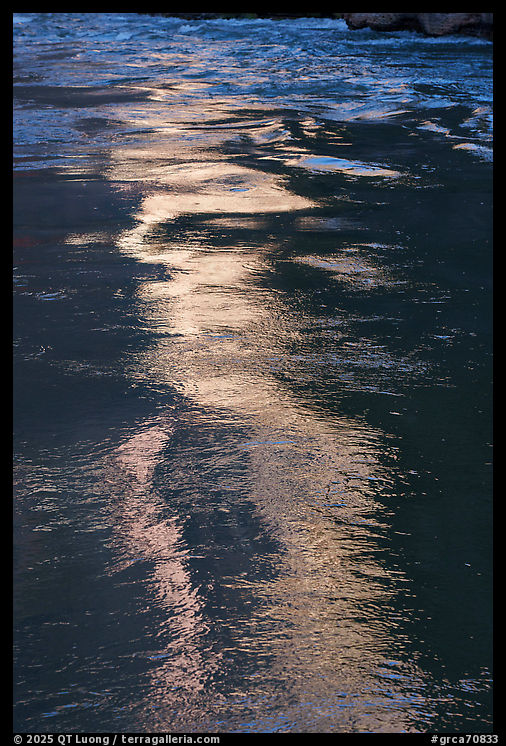

This method of working made it possible to photograph at the tongue of rapids — the V-shaped patch of smooth water at the head of each rapid. There, just before the chaos, the river gathers itself. The current tightens into a dark, glassy V, flanked by choppy riffles or foam. It resembles a liquid arrow drawn taut between canyon walls or boulders, converging into a single path. The surface often turns mirror-like, paradoxically calm — a compressed lens of force just before release. This smoothness sometimes captures distorted canyon reflections. Then, at the tongue’s tip, the water folds and drops into chaos: breaking into crashing waves, frothing haystacks, and explosive turbulence. Visually, it marks a threshold — the river’s transition from order to disorder, from grace to violence — pulling the eye, and the raft, into the heart of the rapid. This is my favorite moment to capture on the river, but the risks to the equipment are high, as even in a medium-size rapid, a towering wave may follow immediately after.

To float the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon is to realize that, despite all efforts to tame it, the river remains fiercely alive. When Glen Canyon Dam was completed, some in the Bureau of Reclamation claimed that the Colorado below it was already a “dead river” — its natural cycles severed, its floods controlled — as justification to propose additional dams in the Grand Canyon. But Time and the River Flowing (1964) was published precisely by the Sierra Club to counter that narrative, revealing through photography and words that the river’s spirit persisted in every eddy, rapid, and shifting reflection, ultimately helping stop those projects. Edward Abbey famously called for removing Glen Canyon Dam in The Hidden Canyon (1977), a demand that once seemed radical but now enters serious conversation as reservoir levels fall and restoration is reimagined. This dynamic between wildness and human control quietly threads through much of my work, from remote national parks to urban waterways. Although they are traditional color landscapes, the photographs presented here engage with questions of intervention, resilience, and our evolving relationship to the natural world. Photographing from the raft is not just about capturing grand views; it is an act of bearing witness to a living force that still shapes the American West — and a call to recognize and protect what remains untamed.

These photographs are truly amazing!

Thank you for sending them for all of us to enjoy.

I also enjoyed reading your commentary which allows us to participate in your experience.

Thank you!