Day 1

At Bonanza Springs, the only water source of its size in more than 1,000 square miles of most arid desert, willows and cottonwoods line up a small canyon for half a mile. The watering hole sustains rare Mojave Desert wildlife including tortoises and bighorn sheep. It is a great place to camp and observe them sipping from the spring. We can only hope that nothing happens to it if the company Cadiz Inc is allowed to go ahead with plans to pump groundwater from a nearby aquifer, extracting 25 times more groundwater than is naturally recharged. Tribal peoples in the region also depend on ancestral water sources for their way of life. Bonanza Springs is located about 25 miles east of Amboy on Route 66. From there, it is only 3 miles on Danby Road, which is nothing more than a rocky and sandy single track, but believe the BLM when they say a high-clearance, 4WD vehicle is required. If you are interested in reading more about my car troubles, the story that I wrote onsite while waiting for the tow truck is included below.

Having left San Jose in the morning, I arrived at the parking lot marked by fences and picnic tables with left than half an hour left before sunset. Distant subjects need stronger light, so before the light started to fade, I headed up a trail that lead views of the oasis from a distance. As the sun went down, I walked back to the oasis, using the soft light for closer images that emphasized the organic shapes.

I had driven almost 500 miles on that day, but it was the last 3 miles that would become something to remember.

The BLM warned that the road to Bonanza Springs in Mojave Trails National Monument is for 4WDs. The NPS often says so for any dirt road, but the first clue that the BLM were more serious was right at the start of the road. Although I was expecting it, when the GPS driving app said to turn left, I wasn’t sure that what I saw was even a viable roadway. I drove past it a short distance before realizing that indeed it was the road and it would be rougher than I’d liked.

Less than a mile in, there was a small wash with big rocks. I hit the brakes to have more time to look how to best navigate around them. When I hit the gas pedal again, I got a sick feeling as the wheels started to spin. I tried to reverse with the same result. The sand wasn’t deep nor fine, but this was sandy enough to get stuck. Since this was the very first day of the trip, I felt stupid. I realized that I forgot to pack the shovel, and instead reached for the backpacking trovel – the one used to dig a cat hole for bathroom needs. I dug some, tried again to move the car to no avail. After adding small rocks, I was able to back. I decided it was nothing but a temporary setback and continued, making sure to keep momentum. This was tricky, as there were quite a few big rocks, so a combination of high clearance and 4WD would have been much welcome.

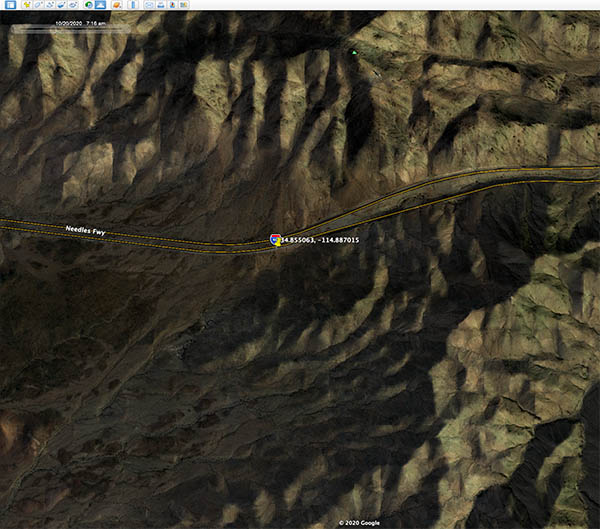

It had taken me less than fifteen minutes to deal with the incident, and I was glad I still had an hour before sunset. Eventually, the road eased up a bit, and I arrived at Bonanza Springs and stayed until dark. The oasis is extensive and a rare sight in the desert. Getting out of the site at night, I made a wrong turn and missed the road. Non-roads and roads are easy to confuse in the desert. After walking back with recorded GPS breadcrumbs on hand, I got back on track. I wondered whether to come out the same way, as I had glimpsed an alternative. Danville Road (yes, this 3-mile stretch of single track had even a name) intersected what appeared to be a wider and better-maintained road that was tempting, but just after a hundred yards, a section appeared sandy under the headlights. The devil you know is better than the one you don’t. I turned around and got back to Danville Road.

As I was making good progress and felt confident, I saw a large rock. I thought I’d have enough clearance and decided to straddle it rather than driving around. It would have worked, except that the tracks were of the same fine gravel that caused me trouble on the way in. With the tires sinking a bit, the vehicle became high-centered. Again, it was less than a mile from the pavement, and now that it was dark, I could see lights of settlements. But I knew nobody would come and help me, and there was no cell phone signal, so I’d have to extricate myself. I reached out for the manual in order to locate the jack. I looked around for rocks to prop it on. I managed to lift the front left tire off the ground, making it possible to fill the space with small rocks. Now the car was no longer touching the big rock. All I had to do was revert the car, and drive around the rock. Upon reaching the old highway 66, having self rescued twice, I felt good.

I was not out of the woods though – if you could say that about driving in the desert. Old Highway 66 was officially closed. There were plenty of signs and posts warning of its closure, but you could drive around them. Sometimes, there were bridges over a wash, in which case the posts would span the entire width of the bridge, but in that case, there was a track going down the wash and around the bridge. People live along the road and have been using it, although it has been years since it was officially closed. I had driven that road two years ago, so the road status would not normally have worried me, but this time, the dashboard started displaying an alarm that read “maximum rpm 3000” with warning signs. I noticed that no matter how I floored the gas pedal, I couldn’t go faster than 55mph on the totally empty road. Worried of breaking down on a closed section of road, I breathed easier when I drove past the last “road closed” sign and reached I-40.

A few miles later, I took exit 120 for Water Road to look for a camping spot. Water Road is paved for a quarter-mile before splitting into dirt roads that I had driven the previous spring looking unsuccessfully for dense stands of Bigelow Cholla Cacti. Numerous places on the web mention it is the largest such collection in California, but back then, I hardly saw any before turning around because the road was degrading.

A commercial truck was parked there, as well as a fellow traveler heading out from the bushes. I thought about parking nearby on the pavement but stuck with my plan to get away from highway noise by driving a dirt road for five minutes. However, after just two minutes of driving, the dashboard now flashed a “low oil pressure, do not drive” sign. I began to understand what happened, and although the dirt road was well graded, I didn’t want to become stranded out of the pavement. I located a spot to pull out, did a u-turn, and parked for the night. When I crouched down to look underneath the engine, sure, there was an alarming oil leak.

Being not much more than a mile from the freeway, I had a cell signal. When I called Lanchi, I only casually mentioned that I hit a rock and the car wasn’t happy. I blamed the European carmaker, WV, for producing such a fragile SUV. As she gave me a “I told you so, this is why I am always worried with you”, I refrained from providing more hairy details, promising to have the rental agency take care of the car. I went to bed and set up my alarm one hour before sunrise time, hopeful that the car would be able to make it less than five miles to the spot along I-40 that a BLM land manager had indicated as a good spot to see the dense stands of Bigelow cacti that had eluded me before. I could not help but marvel at the stars.

In the middle of the night, doubts flashed. Would the car even start? What if it broke down on the interstate? Upon waking up in the morning, I noticed headlights in the distance. Just as I headed out of the bushes, a truck drove by, just like I had driven by the other fellow last night. I envied his ground clearance. My car started, but to my concern, the engine made clicking noises. I kept my speed to the minimum. By a cosmic coincidence, just as the wheels reached the pavement, it came to a sudden stop. Although later It would restart, at this point it did not. Maybe it signaled that the interstate wouldn’t be a safe place to break down?

Although it was 45 minutes before sunrise, there was a group of half a dozen cars gathered there, getting ready for an off-road outing. I waved to them but didn’t even think about asking for help, since it was clear that my only option was to ask Thrifty for a replacement vehicle. I called at about 6:15. When the call ended after quite a few holds, the operator told me to call back at 8, when local agencies would open. They offered a Nissan Versa, but I insisted that I needed an SUV. Even after this misadventure, I still wanted to do more driving on dirt roads, and I had not even packed a tent since I had planned to sleep in the car. The operator agreed to provide one, and when asked for an estimated time, hazarded 2 hours and a half with the caveat that I’d have to wait for a confirmation from AAA. I had rented the car from Thrifty, but at 6am the day before nobody manned their counter, so it was Hertz that provided the car, and now the operator thanked me on behalf of Budget.

I thought that the directions towards the location I had given could not be more clear, but I received another call to confirm them, and yet another. The latter one was from the driver at last. He asked me to use an app to share my location with him. I told him I would have to figure out how to do so, but in the while, if he would tell me where he was located, I would provide him rough directions so he would be headed the right way. His reply Ontario, more than 3 hours away! So much for the day! As the temperature rose to the 90s, there was no shade around. A FedEx truck came for a rest, it’s engine running loudly suggesting the comfort of AC. Instead of being annoyed by the delay, I still felt gratitude that other humans were working to deliver me another car, even it was all my fault.

The Last Road Trip: 1 | 2 | to be continued