The Trail’s Evolution and Artistic Lineage

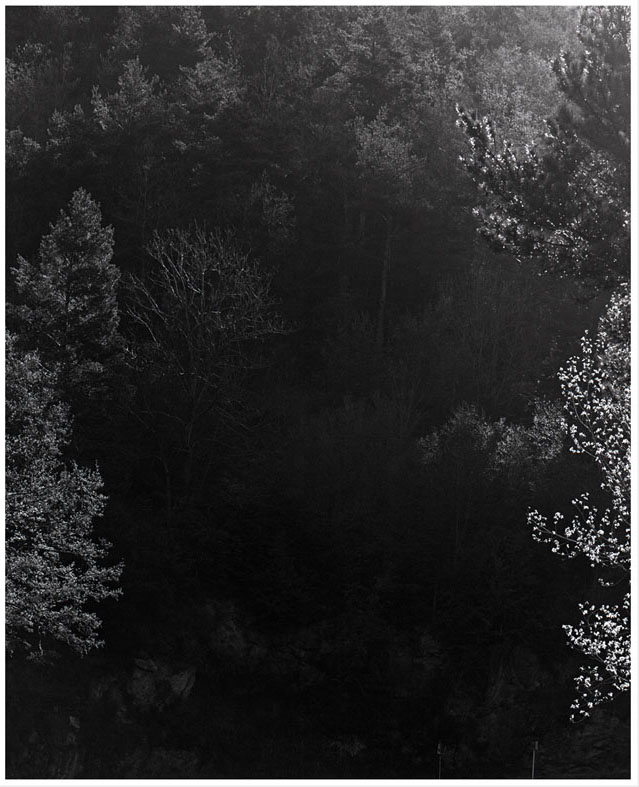

Twenty images from The Trail are at the end of this post. More here.

I have been photographing along the Coyote Creek Trail since that day. The span is long enough that the place has changed, and my understanding of what I was photographing has changed as well. When I began, I didn’t think of the work as belonging to any particular photographic lineage. I was simply drawn to this improbable sliver of nature threading through San Jose. It’s the sort of space most people pass without looking twice: neither wilderness nor park, neither city nor refuge—yet somehow all of them at once.

Where the wild and the human blur

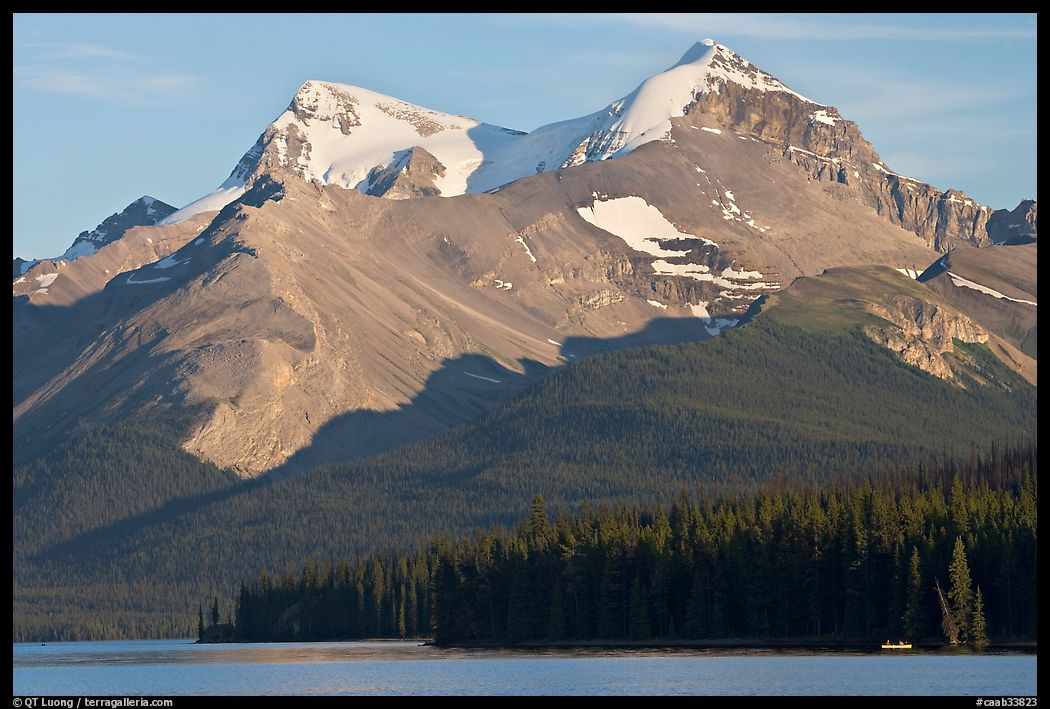

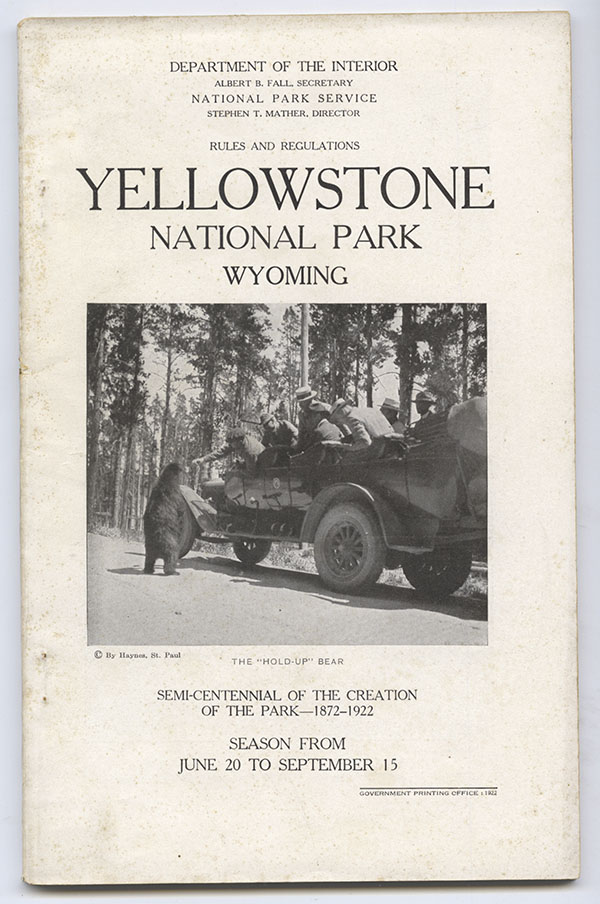

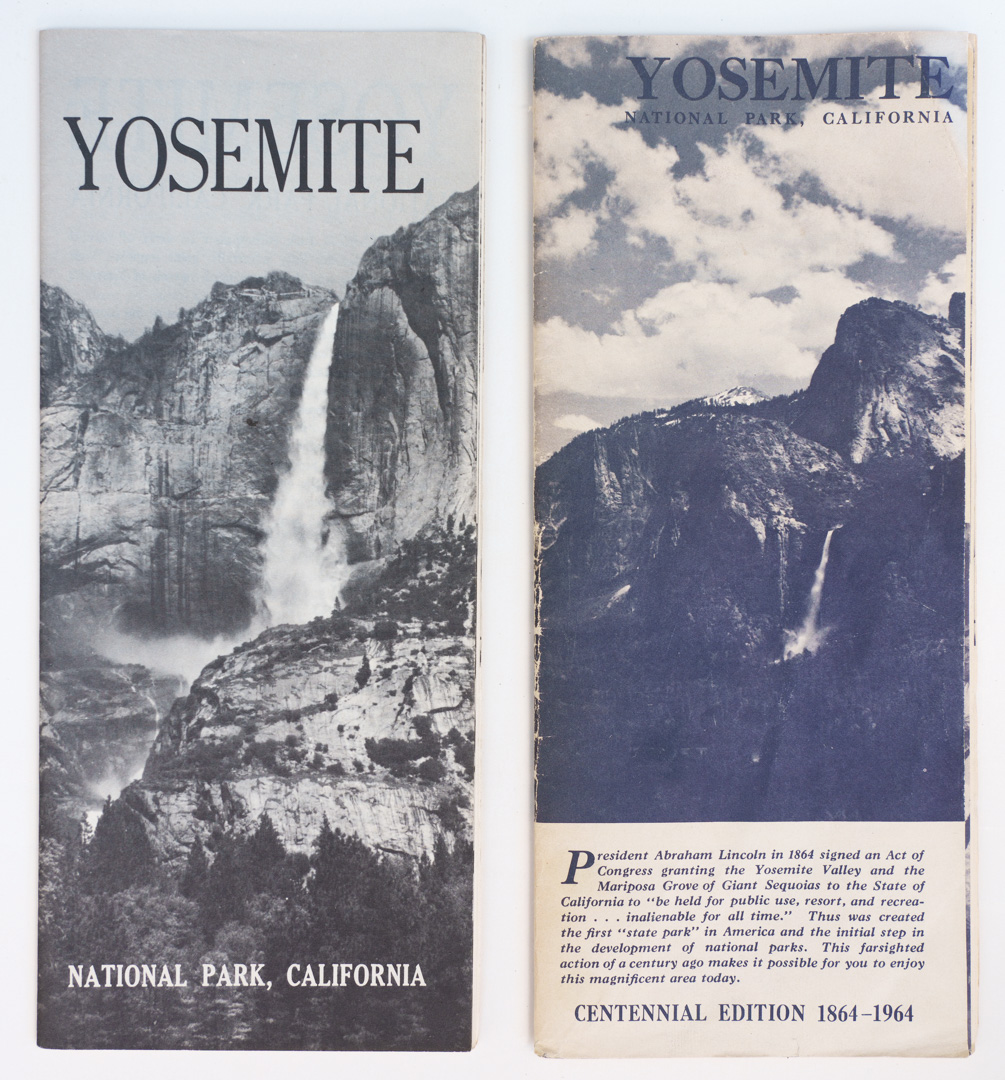

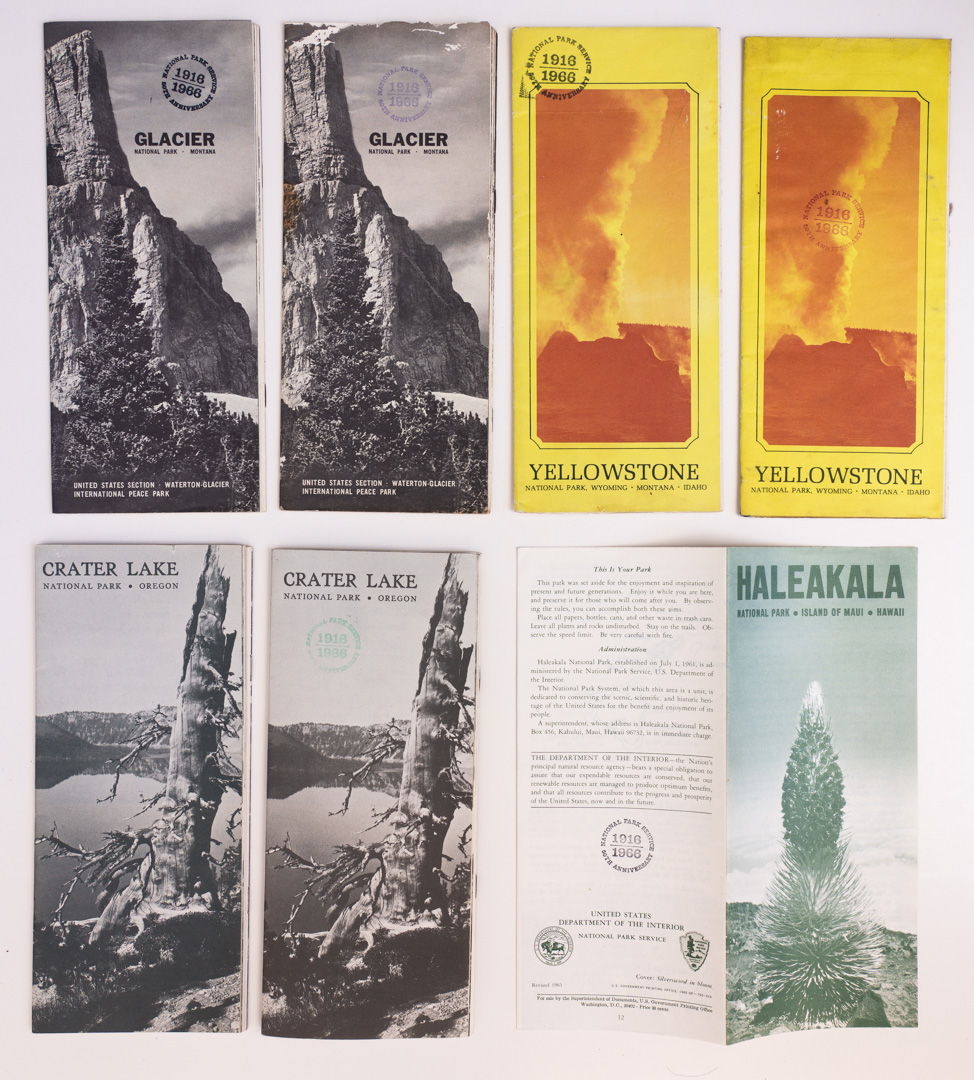

At first, I was consciously seeking the wonder of nature close to home—the kind of everyday astonishment I’ve written about elsewhere, the recognition that awe doesn’t require remoteness but attention (as discussed in The Trouble with Wilderness). I brought to the trail the aesthetic I learned from large-format work—attention to detail and tone, careful framing, hoping to make a modest urban corridor feel as worthy of regard as a mountain peak. In that sense, I was borrowing a vocabulary forged by Ansel Adams and other large-format masters: conservation through elevation, using a “national park” visual language to argue for the value of the local.What interested me next was urban ecology in the simplest sense: how living systems persist inside a built environment. I thought the work would remain there, in that quiet observational space. This early attention to urban ecology aligns with works that find depth in overlooked, human-adjacent nature—Robert Adams’s Los Angeles Spring, attending to green fragments inside a metropolis, and John Gossage’s The Pond, tracing meaning along the shallow edges of neglected land. It also echoes the broader current opened by New Topographics, which reframed the human-altered landscape: a turn away from heroic wilderness toward the human imprint on the everyday, often near home, where restrained observation reveals how the built and the natural interpenetrate. Two of the New Topographics photographers, Joe Deal and Frank Gohlke used the square format to signal a break with romanticism. My project had accidentally walked itself into the company of books about place instead of books about nature. Even then, though, I sensed that the trail was not just habitat. It was also passage—an artery for movement and necessity, not just for wildlife.

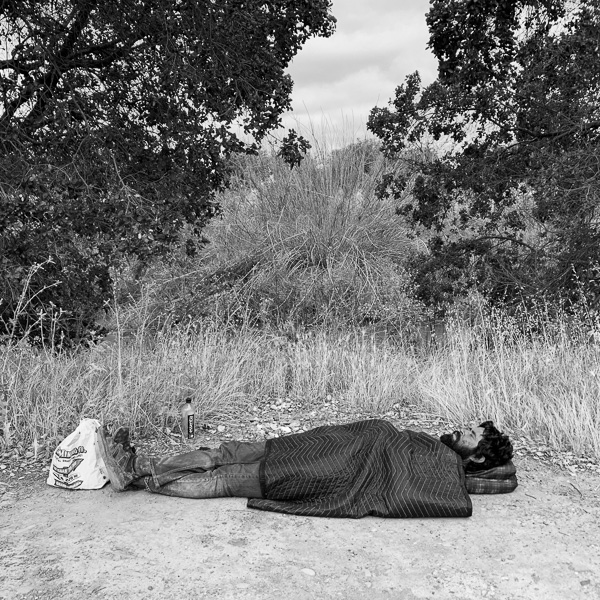

Long-term projects have a way of outgrowing their original premise. You return enough times and eventually you stop seeing “landscape” and start noticing patterns of use: where people stop and rest, where a footpath splits into a private shortcut. Around 2019, I began paying more attention to traces of people living along the creek—small structures, campfires, piles of salvaged material and detritus. At first I photographed only what was left behind: presence without portraiture. I didn’t yet connect that to larger questions. I simply realized that the trail was no longer only a landscape. It was a living negotiation—between shelter and displacement, between public amenity and necessity. Only later did I understand that this shift—photographing traces of habitation—had precedent. Anthony Hernandez worked this territory in Landscapes for the Homeless in Los Angeles in the late 1980s, photographing the spaces occupied by unhoused people, often after they had moved on. Stepping back further, the broader current of social landscape photography—from Stephen Shore to Joel Sternfeld—had already shown how American places can be read as social facts, where the look of the land is inseparable from how we live in it. And in parallel, contemporary ecological art—from Richard Misrach to Subhankar Banerjee—demonstrated how environmental form is bound up with politics. Recognizing that lineage made me look differently at what I had been gathering.

A contested space

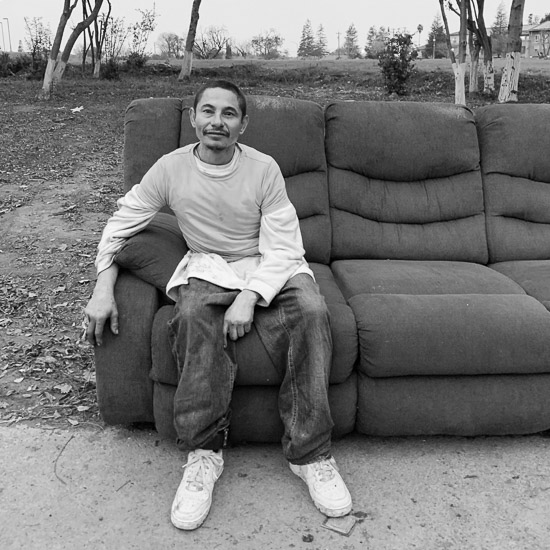

From 2014 to 2022, the work centered on environment and traces. I rarely photographed people directly except on family outings. On that first day we paused—my kids exploring nearby, my brother-in-law taking a drink, my Chihuahua dog Peanut riding calmly in the basket for a break from running half-marathons with me—and I made what I thought was simply a family picture (#11 in the sequence below, which was curated by Judy Walgren and is notably different from the one in my post introducing the project). Years later, in the context of the project, that image read differently: as Judy pointed out, it’s also a picture of privilege—of comfort that travels with you almost invisibly. What began as a private moment became a measure against which other lives on the trail could be seen. That recognition sharpened what I was seeing elsewhere on the trail. I noticed the camps, the movement of belongings, the precarious architectures of daily life—but I continued to photograph at a remove, still believing, perhaps out of habit from my work in parklands, that landscape alone could carry the whole story.By 2023 that no longer felt true. After being away from the trail during the first phase of the COVID pandemic (when I wrongly assumed it wouldn’t allow enough social distancing), I returned to find a place that felt altered. Some encampments had changed or vanished, though the major policy inflection would come later, after the 2024 Supreme Court decision. The changes seemed abrupt partly because I’d been away; the gap compressed time and made absence more visible. I realized that if I didn’t photograph people while they were still living and moving along the corridor, the project would describe only erasure, not presence. For years I had photographed only what remained after the displacements. In 2023, I understood that the people themselves needed to appear before the record collapsed into aftermath.

I understood that to be contemporary, the project needed people. Photographers do not always know, when they start, which tradition their work will eventually join. I certainly didn’t. The tradition I had stepped into—stretching from Evans through Robert Adams to Hernandez—has always understood landscape not only as topography, but as the sum of choices, failures, and pressures embedded in a place. The trail is not just a walking route; it is a ledger of civic intention. Who feels welcome there, and who is pushed out, is not accidental—it is policy made visible. I also saw that the work would be incomplete without acknowledging the full range of users: joggers like me, cyclists, dog walkers, children in strollers. To understand the trail only through homelessness would miss that it is also recreation and ordinary pleasure.

It was only after including people that the shape of the project snapped into focus. The trail began to read not just as environment, but as public space—a corridor negotiated daily by different users. That realization also placed the project alongside work in which geography becomes portraiture: most famously in Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi, where the river is not scenery but a conduit through which human lives take shape in the frame.

From there the lineage widens into artists who treat public space as a social stage: Eugène Atget, patiently mapping Parisian streets, thresholds, and shopfronts; Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York; Helen Levitt’s street theater; William Klein’s charged sidewalks; and the generation of Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Joel Meyerowitz who made the American street a laboratory for seeing—spaces where presence becomes a way of saying “I have a right to be here.” Alongside this, the documentary engagement with marginalized communities—from Mary Ellen Mark to Eugene Richards—models an ethics of attention and proximity that shaped how I approached the trail’s more vulnerable residents. Including people made that conversation explicit. Once people entered the frame, the entire project accelerated. I was no longer photographing environment alone, but relationship—between place and the lives unfolding within it.

The Long View

When you return to the same ground for a decade, your photographs are not taken from above (as in “parachuted photojournalism”), they are taken from within. I was not passing through the trail as an outsider collecting scenes. I was learning how it lives at different speeds: the speed of a runner, of a hawk circling over the wetlands, of someone building a fragile shelter before the next abatement.

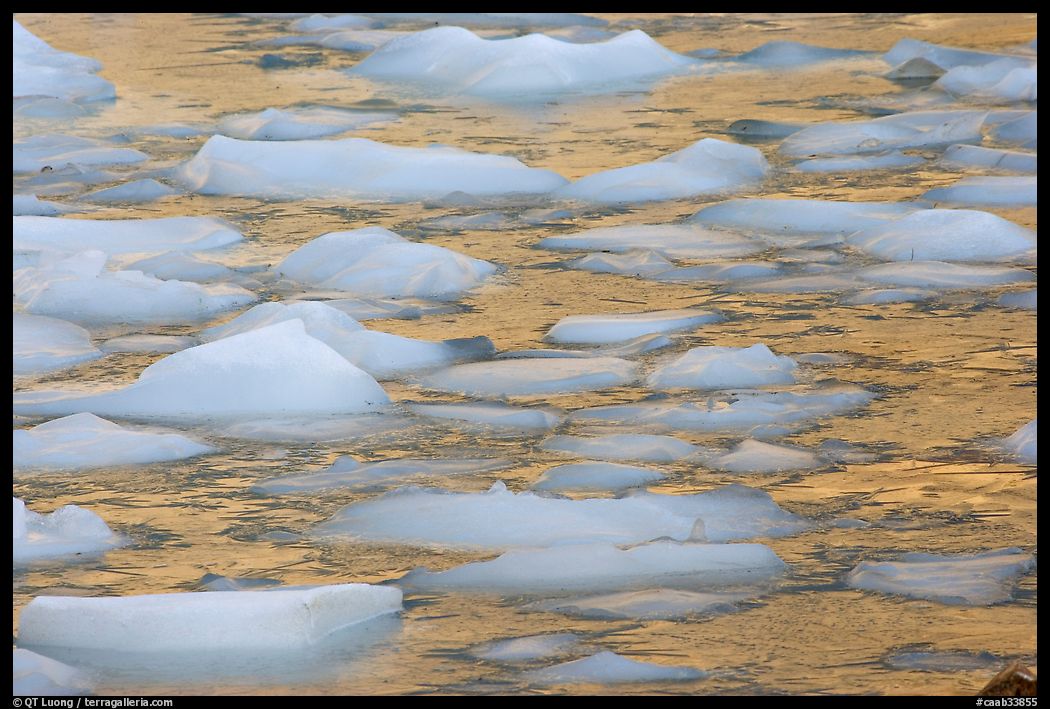

Returning again and again, I found that photographing the same stretches of trail over years was not repetition but accumulation. The project gained duration as narrative: a record of change, in both land and lives. This, too, has a lineage. Camilo José Vergara documented urban America over decades from fixed vantage points; William Christenberry photographed Hale County across a lifetime; Mark Klett made landscape and time inseparable, developing a rephotography practice that I’ve adopted on the trail—returning to precise locations, seasons, and angles so that small shifts become legible as part of a larger arc; and, close to my own background in large-format work, Jem Southam has used color and patient seasonal return to register incremental change along rivers, ponds, and coasts.

This is where long-term practice becomes more than endurance. It becomes comprehension. Some readers assume that photographing close to home is merely a practical choice, but the opposite is true: the closer the place, the longer it takes to see it clearly. The Coyote Creek Trail is not the heroic landscape of the national parks where I worked for decades. Here, nothing announces itself. Meaning has to be found, not encountered. It accumulates through attention. This, too, is part of its lineage. Gossage knew that “minor” landscapes reveal major truths. Adams knew that ecological questions live inside the ordinary. Christenberry knew that repetition is a form of fidelity.

Small place, universal concerns

One unexpected realization was how few major photographic works are about trails specifically — not parks, not streets, but official multi-use corridors where walkers, cyclists, and unhoused residents occupy the same narrow strip. A trail is very different from a park. A park is a destination. A trail is passage, friction, negotiation. Sternfeld photographed the High Line in Manhattan before it became a park. The Bloomingdale Trail in Chicago, the BeltLine in Atlanta, the Promenade Plantée in Paris have all been documented, but as architecture, infrastructure, or planning success story—not as a contested space or lived social ecosystem.Once I realized this, the project stopped feeling like a local study and began to feel like something larger—a contribution to a lineage that had room for it. I renamed the “Coyote Creek Trail Project” simply The Trail to point beyond one locale—to the universal question of our place in the land—and as a quiet nod to John Gossage’s The Pond, whose generic title helped transform a specific site into a larger field of meaning. When people arrive in the frame, time arrives with them. The trail was never “nature with intrusions”; it was always a place whose ecologies are entwined with human pressures. Wild pigs navigate that corridor alongside people hauling water or bicycle commuters. Only when I began photographing people did the larger arc become visible: The Trail as a portrait of use—the use of land, of policy, of daily endurance. The environment no longer read as backdrop, but as a stage of consequences.

Although I began photographing The Trail in 2014, the core of the work belongs to the past several years. It became a 2020s subject the moment the social stakes could no longer be separated from the environmental ones: habitat or habitation? What keeps me returning is the same thing that keeps certain projects alive across decades: the understanding that a place is not a static scene but a moving concern. Ecological restoration is a part. Displacement is another. Recreation is a third. The trail holds all three, simultaneously.

We are past the era when “the environment” meant pristine distance. Ecology now exists where people do. If there is a contemporary analogue to wilderness photography, it is not deep in roadless acreage—it is here, in the contested ecologies where people with vastly different stakes meet the same piece of land. That is why I no longer see The Trail as a shift away from landscape photography, but as its continuation into the present tense. This is what a 21st-century landscape looks like: shared, politicized, unevenly distributed, and constantly negotiated.

I have photographed national parks for a quarter century, in places defined by scale and remoteness. The Coyote Creek Trail is the opposite: small, proximate, woven into the city. Yet it has revealed itself to be no smaller a subject because the questions taking shape here are urgent: Who belongs in public space? What counts as nature? Where ecological care collides with social cost?

Lineage matters

Some artists resist speaking about lineage, as if acknowledging predecessors might dilute originality, or as if dialog meant forfeiting your voice. I’ve come to feel the opposite: lineage enlarges the work. It clarifies its place in a broader conversation. Knowing where your work sits in the history of the medium is a form of consciousness. A photograph is always, in some way, a reply: to what came before, to what is happening now, and to what might come next. I didn’t know at the outset which conversation The Trail belonged to.Looking back now, I can name the line of descent: Atget’s patient cataloguing of public space; Evans’s synthesis of people, structure, and place; Christenberry and Klett’s return to the same ground across years; Robert Adams’s attention to the edges of sprawl; Gossage’s belief that overlooked land carries narrative; Hernandez’s recognition that public land is also social shelter; Soth’s understanding that a landscape becomes human when its people are seen.

This is not a list of influences in the conventional sense. It is more accurate to say that, over time, my work found its ancestors. The lineage arrived not as aesthetic imitation, but as recognition.

The trail has taught me that persistence is a form of seeing. What begins as attention becomes duration; what endures becomes meaning. Ten years in, I understand that I was not just photographing an overlooked corridor—I was walking into a history, and eventually I recognized the door I had entered. The Coyote Creek Trail is a physical path, yes, but for me it has also become a path through the medium itself: from urban ecology to social presence, from surface to structure, from looking to witnessing. If a lineage emerged, it is because the place required one. In that sense, this project did not start with history, but it ended by joining it.