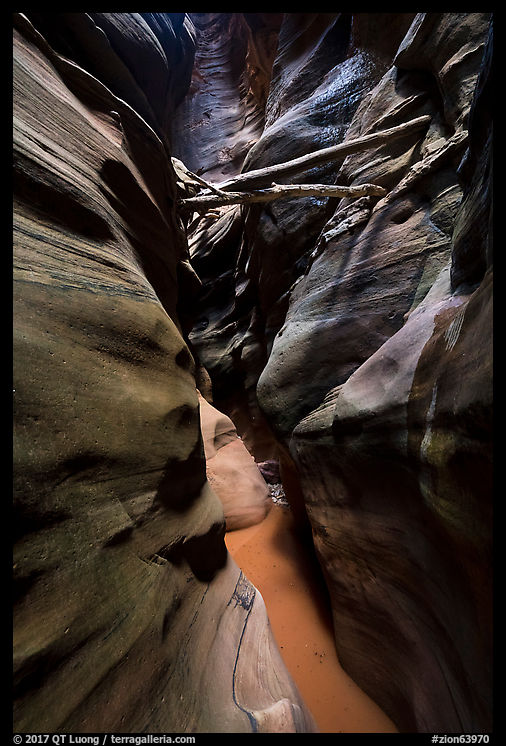

The Subway in Zion National Park is a unique tunnel-like canyon with water flowing over polished rocks and small emerald pools, often bathed in an ethereal light that confers to it the atmosphere of a crypt. For hikers, it is accessed through the “bottom-up” strenuous 7-mile round-trip hike through the Left Fork of North Creek that requires a bit of route finding, creek crossing, and scrambling over rocks.

The river hike

You start with a relatively flat half-mile hike to the rim. Once you make your way down (400 feet in elevation) to the canyon via a very steep trail, look back at the lava outcrop you just hiked down from, so that you don’t miss it on the climb out. Once at the bottom of the canyon, the overall route is quite clear: you just follow the creek up. The precise path is much less clear, since there is no officially maintained trail but rather a number of user trails on both sides that often vanish suddenly, leaving you wondering whether to scramble on the left side, right side, or in the creek until the next user trail. You frequently need to hop over boulders or duck under branches. At first, I tried to avoid getting my feet wet, but once I accepted it was going to happen, hiking became much simpler — I didn’t hesitate anymore to hike in or cross the streambed. This part of the hike is densely vegetated and pretty in a non-descript way.

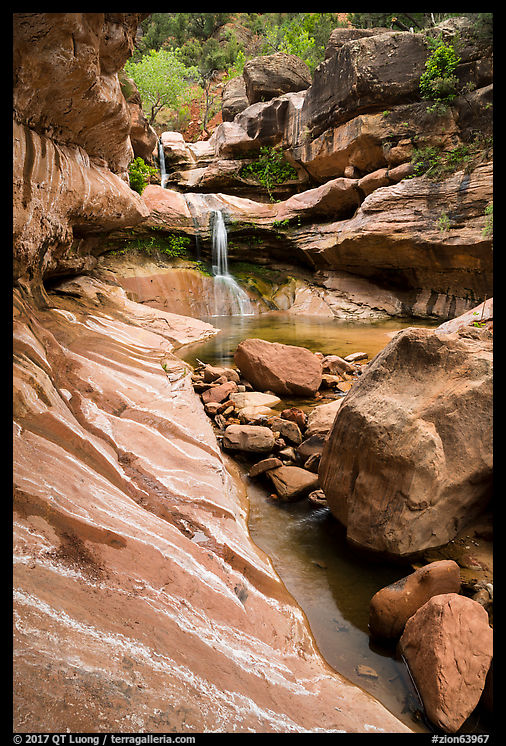

The waterfalls

The scenery gets more interesting 3.25 miles into the hike. At this point, you come upon a series of stepped cascades over red travertine terraces called Archangel Falls which would be worth the hike alone. A bit further, two waterfalls flow in front of a beautiful alcove.

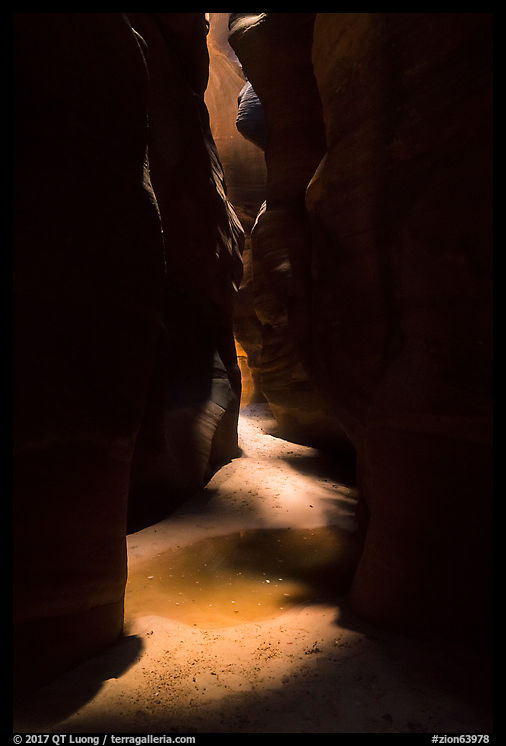

The next attraction is a little 12-inch-wide crack that funnels the whole stream in a unique way. If you get close, it makes for very striking compositions, especially in the autumn when surrounded by fallen leaves.

The Subway

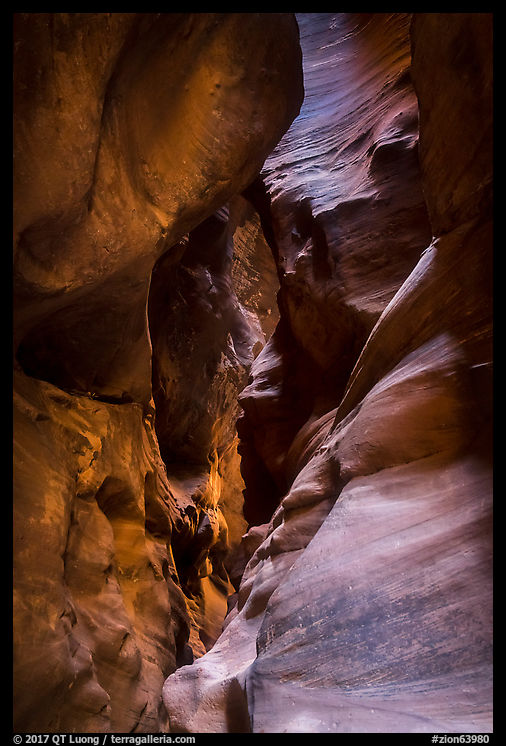

At the Subway itself, there are two classic views, shooting upstream with pools and cascades in the foreground, and downstream from the back, which reveals the tunnel shape of the Subway (see last section for pictures). You should make sure that you go as far as you can, since the back of the Subway is a striking sculptured rock wall foregrounded by pools. They can be only waist-deep or require a swim to get across. If the deep pools don’t stop your progression, the wall will, so you cannot access the beautiful sections above, and need to turn back the way you came. To see them, if you are prepared for canyoneering, you can take the adventurous

“top-down” route (9.5 miles one-way), which I find much more rewarding. It requires more difficult route finding, a few swims in cold water, and a few short rappels. However, packing serious photographic equipment is not easy, and you’ll likely arrive at the Subway later in the day.

Equipment

Choose footwear that continues to work well once wet! Canyoneering boots can be rented in Springdale. Hiking poles can be useful as well. The Subway is often windier and colder than the rest of the canyon so pack warm clothing. Like for all long days, bring plenty of water (or a filter), and a light can be useful.

The light can be dim in the Subway, requiring multi-second exposures at ISO 100. Most compositions involve some flowing water that benefit from a longer exposure. Notice how “choppy” the waterfall looks in the image below. On my last visit to Zion’s Subway, I was delighted by this surprise visitor at Archangel Falls, since I’d never seen them in Zion before. I had to use a shutter speed of 1/60s as he was moving quite fast. For those two reasons, make sure to pack a tripod despite the long hike.

A polarizing filter is another absolute necessity, as it removes the glare from wet sandstone resulting in considerably more saturated color, and it is sufficient to slow down exposures for smooth water. I haven’t needed a lens outside of the super wide-angle (17mm) to normal range.

Permits

The Subway is located in the Zion Wilderness. Both the “bottom-up” and “top-down” routes require the same backcountry permit. Check

the NPS page for details. Currently, there are 4 options: Advance Lottery, Reservations, Last Minute Drawing, Walk-ins. There is a quota of only about 80 per day, and no camping is allowed. The location has become very popular in recent years, especially in autumn, so be sure to book the permits far in advance of your trip! The

Advanced Lottery opens 3 months before trip date. You can have all members of your party apply ($5 to enter) to maximize your chances. Choose “Left Fork of North Creek”.

If you are awarded a permit, you need to pick it up on the day before or the day of your trip either at the Zion Canyon or Kolob Canyon visitor center. If you didn’t win one, by lining up early at the visitor center (check opening times for the backcountry/wilderness desk, which is earlier than regular visitor center hours) you might be able to get one if you are lucky, especially if you are going solo. Many folks do that for all sorts of destinations, so if you were awarded a permit online, come later to avoid the line.

No guiding is permitted in the Zion Wilderness. If you signed up for a photo tour or workshop and your leader takes you to the Subway, he is certainly afoul of park regulations, and recently park rangers have been cracking down on the practice.

Trailhead

To get to the trailhead, drive west out Zion National Park on Hwy 9, and in the town of Virgin, turn right into the Kolob Terrace Road and follow it for 8.2 miles to a trailhead on your right marked as “North Fork”. From Zion National Park’s entrance it takes about 35 min. There is a toilet, but no water.

Timing

Overall, fall offers the best conditions for this hike, with a combination of low water flow, no direct sunlight on the Subway, and mild temperatures around 75F. High water flow, especially in April can hamper hiking, but enhances the cascades. The hike is popular with photographers in the fall, but less so with the general public, making it easier to get last-minute permits. Fall foliage, which usually peaks around the first week of November, adds a beautiful accent, although I find the contrast of green leaves and red rock pleasing as well. Like all canyon hikes, you should avoid the Subway if there is a danger of flash floods. Summers are hot, and winters bring snow and ice.

If you hike in the fall, you should start from the trailhead at sunrise or earlier, which should allow you to reach the Subway at midday with a few stops to photograph the waterfalls before they get in the full sun. Due to the rugged terrain, count on hiking only between 1 and 2 miles per hour for a total of between 6 and 9 hours. You’ll most likely spend a whole day for this strenuous but rewarding hike.

Mid-afternoon, Mid-October, cloudy sky

Mid-afternoon, Mid-October, cloudy sky

3:22PM, May 15, cloudy sky

6:19PM, June 15, clear sky

The waterfalls and the Subway are best photographed in reflected light, which means that they are in the shade and illuminated by the sun reflecting from a rock wall but not striking the scene directly. The second best light is cloudy or with the sun down. The worst light is direct sunlight, when the contrast and shadows reduce the beauty of the scene. In the late spring and summer, sunlight reaches the Subway during midday, so you should plan to photograph earlier or later. In the fall, the Subway remains in the shade all day.

The standards for the “Subway glow” were established by Michael Fatali in his iconic and pioneering photograph “Mystic Waters”. They consist of emerald colors in the pools contrasted with a warm glow on the tunnel part of the Subway. In three visits, I have not observed those conditions. I don’t think they are not necessary to create a compelling image, as other renditions are quite beautiful too. Do you agree? If you want to catch the glow, the consensus says that it occurs on a clear day from late morning into early afternoon, but I saw a few mentions of late afternoon as well. Please confirm in the comments if you have observed this light directly and feel free to link to your photograph!

More images of the Left Fork

More images of the Subway

Mid-afternoon, Mid-October, cloudy sky

Mid-afternoon, Mid-October, cloudy sky

IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards – Arts and Photography Gold Medal

Administered by the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA), for nearly 30 years, the

IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards – Arts and Photography Gold Medal

Administered by the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA), for nearly 30 years, the

Foreword INDIES Book of the Year – Nature Gold Winner, Travel Silver Winner, Photography Honorable Mention

Founded in 1998, Foreword Reviews is the only independent media company completely devoted to independent publishing. They define the term more broadly than others as it includes all but the “Big 5” – Rizzoli won the award several times.

Foreword INDIES Book of the Year – Nature Gold Winner, Travel Silver Winner, Photography Honorable Mention

Founded in 1998, Foreword Reviews is the only independent media company completely devoted to independent publishing. They define the term more broadly than others as it includes all but the “Big 5” – Rizzoli won the award several times.

National Indie Excellence Awards – Photography Winner

The

National Indie Excellence Awards – Photography Winner

The  Nautilus Book Awards – Photography and Arts Silver Winner

Nautilus Book Awards – Photography and Arts Silver Winner