Yellowstone: the other Grand Canyon

3 Comments

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone National Park. When President Grant signed the Act of Dedication (you can read its brief text here) on March 1, 1872, setting aside Yellowstone “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people”, the first national park in the world was established. Yellowstone National Park is internationally renowned for its geothermal features, and also its wild animal population. They are not by any means the only wonders in the park. As early National Park Service visitor guides put it:

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone affords a spectacle worthy of a national park were there no geysers.

Since this was a land that almost nobody on the East Coast had seen with their own eyes, artist representations were instrumental in the establishment of the park. Ferdinand Hayden, director of the United States Geological Survey had brought along his 1871 survey of the region a photographer and a painter. While the photographs by William Henry Jackson helped convince that the geothermal wonders were real, the colorful sketches of Thomas Moran captured the imagination. As romantic as they appear, their colors are highly accurate, and so are their depiction of geological elements. Released at about the same time as the establishment of the park, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872), Moran’s first large-scale painting was immediately bought by Congress for display in the U.S. Capitol and became popular with the public (discussion by Smithsonian American Art Museum curators). As wonderful as they are, the geysers and other hot water phenomena do not inspire the kind of sublime awe described by Nathanial Langford, a member of General Washburn’s expedition in 1870:

The place where I obtained the best and most terrible view of the canyon was a narrow projecting point situated two to three miles below the lower fall. Standing there or rather lying there for greater safety, I thought how utterly impossible it would be to describe to another the sensations inspired by such a presence. As I took in the scene, I realized my own littleness, my helplessness, my dread exposure to destruction, my inability to cope with or even comprehend the mighty architecture of nature.

Thomas Moran would go on to paint many of the landmark western landscapes, including several national parks, but recognizing the significance of his particular connection with Yellowstone, he adopted the new signature of T-Y-M – with “Yellowstone” his new middle name! As can be seen in this selection of Moran’s Yellowstone work from the NPS, the artist who sought to associate with Yellowstone the most had a favorite subject in the park, to which he returned time and time again: the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone.

The modern “Unigrid” national park visitor guides have all featured geothermal features on the cover, with the picture of Old Faithful Geyser gracing the current one. However, a look at older visitor guide brochures from the years 1935 to 1974 reveals that out of 20 different illustrated cover designs, 14 featured the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, invariably pictured with Lower Falls.

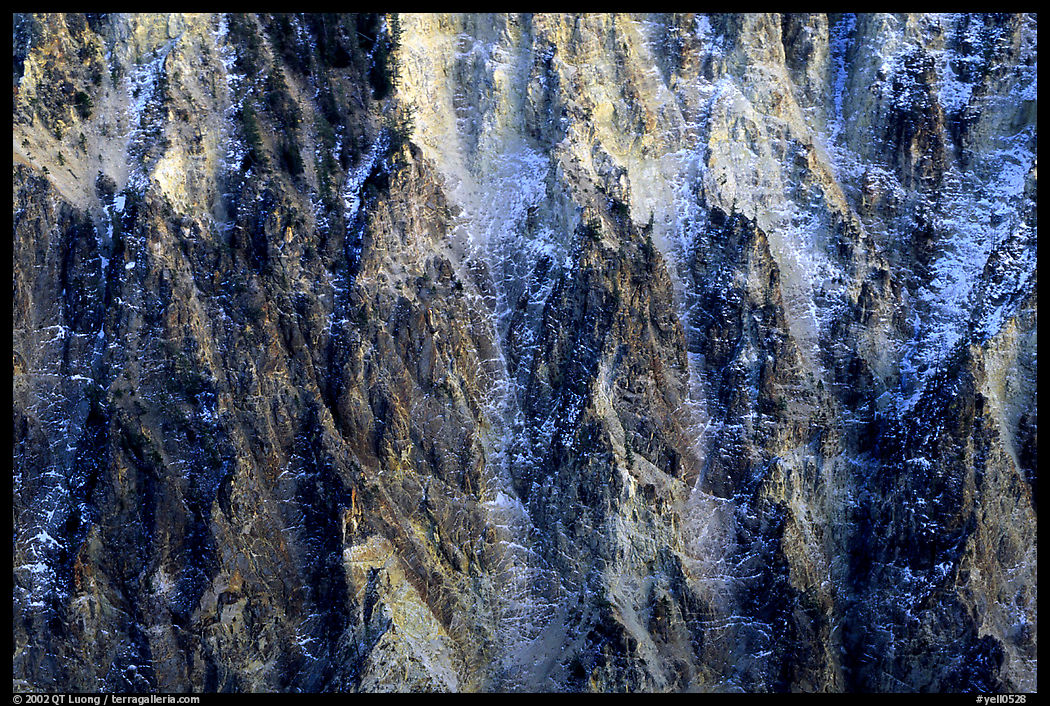

The Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona is simply referred to as “The” Grand Canyon, being by far the largest and most impressive of all the canyons in the country. The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone’s claim to fame is different. While it has a respectable size, 20 miles long, 800 to 1,200 feet deep, and 1,500 to 4,000 feet wide, making it the most impressive geological feature in the park, what causes it to stand out among all canyons are the colors. The primary rock in the canyon is volcanic Rhyolite, which erodes into fantastically jagged formations. Hydrothermal activity, still visible in the form of steam, was responsible for altering the rock into a rainbow of hues. Adding to the interest are the two waterfalls of the Yellowstone River after which the park was named, Upper Falls (100 feet high) and Lower Falls (300 feet high).

Inspiration Point

Overlooks along the north and south rim drives offer sweeping views and different perspectives. When Nathanial Langford experienced the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone as quoted above, he was standing at a spot that no longer exists, Promontory Point. In 1975, about a century after his visit, an earthquake of Richter scale 6 caused the promontory jutting into the center of the canyon to collapse and its remaining tip to become unstable. Still, the closest you can get to the old Promontory Point, Inspiration Point, offers an impressive view of the canyon from where you look almost straight down to the Yellowstone River a thousand feet below. The steep slopes are deeply carved, at places forming jagged rocky spires. When viewed on a sunny midday, yellows and whites dominate, however, softer light makes more visible a profusion of hues spanning the entire spectrum from reds and oranges to yellows. Since the days were sunny, I photographed from the late afternoon when the lower angle of the sun highlighted textures, to the early evening, when the even light reveals the colors.

When I visited in the 1990s, as I was primarily photographing with the 5×7 large-format camera, my main focus was on capturing “big picture” expensive views that give you the sense of being there. However, there also are endless opportunities to create more abstract images by focusing on the details of the landscape from any overlook. Inspiration Point is located on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. From Canyon Junction, follow Grand Loop Rd south for 1.2 miles and turn west (left) on the one-way N Rim Dr and then after 1.3 miles west (right) onto a 0.8-mile spur road. It’s a short 0.1-mile stroll to the overlook.

Artist Point

From Inspiration Point, you can barely see a waterfall in the distance, as it is partly hidden by the canyon wall. That waterfall is the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River, by far the most spectacular of the two waterfalls in the canyon. Plunging 300 feet, twice the height of Niagara Falls, it is the largest waterfall in the park, and one of the most impressive features of the canyon. There are several excellent views of the Lower Falls.

Artist Point is the most iconic viewpoint in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. From there the steep canyon walls perfectly frame the waterfall located about a mile away from you, making it possible to depict the canyon with its most notable feature. The waterfall flows year-round and even at its lowest flow there is still plenty of water. From my several visits, I made my favorite image on the very first one, on an October overcast day after a recent snowfall. The freezing temperatures amplified the thermal steam from the canyon, whereas a dusting of snow critically differentiated both sides of the canyon. Placing the river two-thirds on the right created an asymmetrical balance between the lighter left side and the heavier right side. Not only the softer light reveals more of the colors, but also the flatter light resulted in a painterly quality in which all the textures stood out. Naturally, I excluded the bright overcast sky from the composition.

The waterfalls are facing east, so on sunny days, morning generally provides better light on them. On a clear summer morning, the blue sky was perfectly exposed, but it did not add much interest besides rather disharmonious color contrast. Its presence lends a different feel to the image, but I preferred the composition with the sky excluded. This caused Lower Falls to attract the eye as one the brightest area. As the early morning sun was grazing the right side of the canyon, it created an alternation of diagonal sunlit ridges and shadows more remarkable with its contrast than the uniformly lit left side, so I filled most of the frame with it, its large visual mass counterbalancing the waterfall. Artist Point is located on the south rim at the end of Artist Point Road that starts 2.2 miles south of Canyon Junction just past the Chittenden Memorial Bridge over the Yellowstone River, and it is a short stroll to the overlook.

Closer Lower Falls Views

For a closer view of Lower Falls, you can try Lookout Point, on the north rim – on your way to Inspiration Point, also a short stroll. If you’d like to explore more viewpoints, you can hike the 3.3-mile section of the North Rim Trail between Upper Falls and Inspiration Point. Little of the canyon is visible from the roads besides the overlooks. I made the photograph in pre-dawn light. At that time, there were no shadows or excessive contrast in the canyon, yet the light was directional enough to provide some shading and differentiate the two sides of the canyon, lending depth to the scene.

The Brink of the Falls Trail, as it names implies, takes you to the brink of Lower Falls from the north rim, but while you will come closest to Lower Falls, you will be above its back and therefore without a view of the waterfall. The closest view is from Uncle Tom’s Trail, named after the nickname of H.F. Richardson, a Bozeman, MT resident who built a primitive version of the trail on which he guided visitors for a fee from 1898 to 1906. They had to be ferried across the Yellowstone River (the bridge over the Yellowstone was built in 1903) and then grab ropes to negotiate the steep terrain. Nowadays, the trail is much safer but remains quite unique and strenuous, with 500 feet elevation loss in just 0.7 miles. Paved switchbacks lead to a vertiginous steel staircase of 328 steps built down the south wall of the canyon and descending 3/4 of the way down its height. That is the lowest you can descend into the canyon, where off-trail hiking is prohibited. You cannot longer get to the vantage point pictured on the cover of the historic visitor guide with a white cover (on the second row). The trailhead is on the south rim along Artist Point Drive.

The water volume varies between 5,000 gallons of water per second in the fall and 60,000 gallons of water per second in the spring. In 2016, to celebrate the centennial of the National Park Service, we went on a family road trip to Yellowstone. On that early summer visit, I timed my visit for late morning, hoping that the sun in my back would produce a rainbow in the mist of the fall. Sure enough, the rainbow was there. However, the lower part of the trail was drenched unlike during my fall visit. Having left the spinning rain deflector at home, it was too wet for photography, and I had to content myself with a dryer viewpoint further up. Clouds were moving quickly across the sky, and I waited for a moment when their projected shadows on the canyon walls made the waterfall and mist stand out in light.

Hi QT

I just did my 1st road trip in three years. It felt really

good to be back out on the road, really, really good.

Thanks for telling us the “Why” in this blog. Knowing

the reason you made decisions is very helpful in improving

my own photography. Keep it up!

Thanks much,

Jeff

Glad to hear the comments are helpful to you! I had to go on professional trips in that period, mostly for Our National Monuments, but we also just did our first family trip afar in three years.

Hi QT, I am considering a trip to Yellowstone, so thank you for the blog post. I shot large format for years and miss it. I don’t really miss all the scanning that goes along with it though 🙂