Canon EF 24-105/4 L IS vs 24-70/2.8 L

I am often asked for lens recommendations (although I have already wrote a page of technical comments). For those wishing to make photographs similar to mine, and using a Canon full frame camera, I always suggest the Canon 25-105/4 L IS as an all-purpose lens. I consider this lens to be the best zoom ever made by Canon, when used with the appropriate software.

In 2006, after much testing (which will be the subject of a separate post), I replaced my 24-70/2.8, a highly regarded lens which had been my main all-purpose lens, with the 24-105/4. However, as a recent mishap has ruined my 24-105, I’ve been using again the 24-70/2.8 for a few weeks, which reminded me of how much I prefer the 24-105. I am again trying to find a good sample of the 24-105. I thought that would be a good time to share my observations, based on years of use of both lenses.

The 24-105 (left) is collapsed @24mm and extended @105mm. The 24-70 (right) is collapsed @70mm and extended @24mm.

| 24-105/f4 IS | 24-70/f2.8 | |

|---|---|---|

| focal lengths | Extra range of 70-105 very useful (for ex. portrait work), or if lens is coupled with 100-400. | |

| max aperture | Extra f-stop of 2.8 useful for moving subjects and blurring backgrounds, brighter viewfinder | |

| close focus | 0.45 / 1.48ft, 0.23x magnification | 0.38m / 1.3ft, 0.29x magnification |

| IS | Image stabilization provides 3 f-stops of stability, more than makes up for max aperture with static subjects, useful for getting more DOF or low light shooting | |

| AF | USM. | USM. Faster and more accurate in low light thanks to f2.8 aperture (many AF cross-sensors are disabled at f4) |

| Size DxL | 83.5 x 107 mm only slightly smaller when used without hood | 83.2 x 123 mm doesn’t include hood, which adds significant bulk |

| Weight | 23.6 oz (670g) significantly lighter | 33.6 oz (950g) | Construction | Sealed. Plastic barrel. | Sealed. Metal barrel. |

| Lens hood | Shallow lens hood attached to extending barrel of lens, optimal only at 24mm. Easily knocked. | Uniquely deep lens hood attached to fixed body of lens, takes advantage of the fact that lens is extended @ 24mm and retracted @ 70mm. Optimal at both 24mm and 70mm. Very efficient and solid, but requires removal to rotate polariser. |

| Zoom creep | long focals, in particular pointed down (annoying for close-ups) | 24-28 range when pointed straight up (rarely used that way) |

| Sharpness | Sharper at all focal lengths and apertures. Excellent wide open at short focal lengths | |

| Vignetting | @24mm: strong (1.5) wide open, mild (0.75) by f8 @50mm: mild wide open, very slight by f8 @105mm: slight wide open, very slight by f8 | @ all focals: slight (0.5 f-stops) wide open, none by f5.6 |

| Distortion | strong barrel @24, slight pincushion @50, moderate pincushion @105 | moderate barrel @24mm, none @50, slight pincushion @70 |

| Flare | Lots of ghosting when bright light source in frame | Little ghosting |

| Price (11/2009) | $1200 @ BH $1260 @ amazon | $1300 @ BH $1300 @ amazon |

Both lenses include features found in L lenses and often missing in lesser lenses such as constant aperture, weather sealing, internal focus, non-rotating filter ring.

For my style of photography, where I often seek a large depth of field, the extra f-stop of the 24-70 is much less interesting than the IS and extra range of the 24-105. In addition, the sharpness of the 24-105 is exceptional for an optic with such a wide range and (relatively) small size and weight. If a wider aperture is desired, it is probably more effective to switch to fixed-focal lenses, which will offer a maximal aperture of f1.4 or f2.

The main drawbacks of the 24-105 are the strong vignetting and distortion at 24mm. Canon would probably have been able to produce a lens exempt from those shortcomings, but this would have come as a cost in size and weight. The lens was released in 2005, when the switch to digital photography was well underway. In digital photography, those shortcomings can be automatically fixed in post-processing by several softwares, including DPP, Canon’s (free) raw digital conversion software, and DxO Optics Pro, which I use. On the other hand, no amount of post-processing can make up for lesser sharpness. This is one case where a newer technology has changed the way one needs to look at an old problem (optical performance).

My main gripe with this lens is that if a bright light source (such as the sun or a street lamp by night) is included in the frame, flare is prominent, under the form of ghost hexagons of the shape of the aperture blades. I cope by switching to my 17-40/4 (much less affected by that problem) in those situations. This applies only to a limited number of situations, so the compromise is worth it.

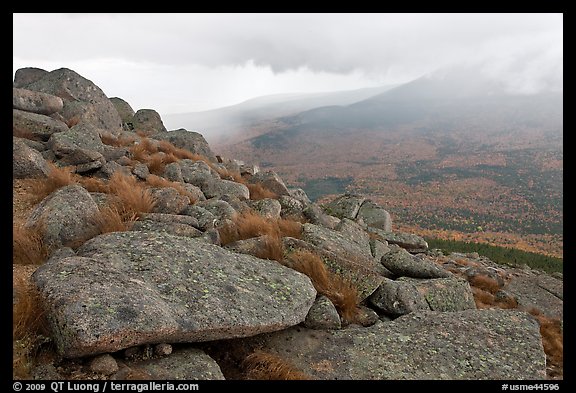

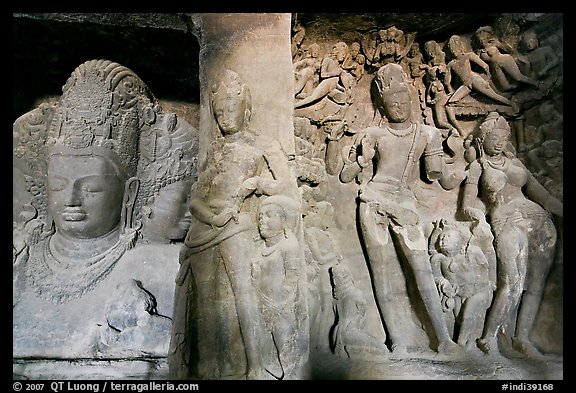

f/4.0 1/4s ISO 1600 24mm

f/4.0 1/10s ISO 1600 24mm

The combination of IS and high sharpness wide open at 24mm has provided me with new opportunities. In the Elephanta Caves near Mumbai, tripods are strictly prohibited. Yet I was able to produce sharp images by hand-holding at shutters speeds of 1/4-1/8 s, shooting at 24mm wide open. A similar situation occured at dusk inside the capsule of the London Eye.