Photo spot 52: Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park – Long Draw route

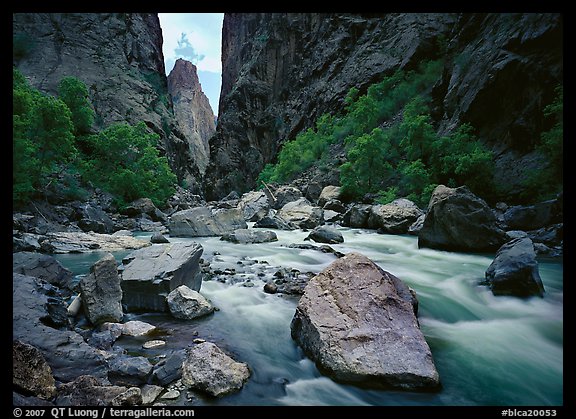

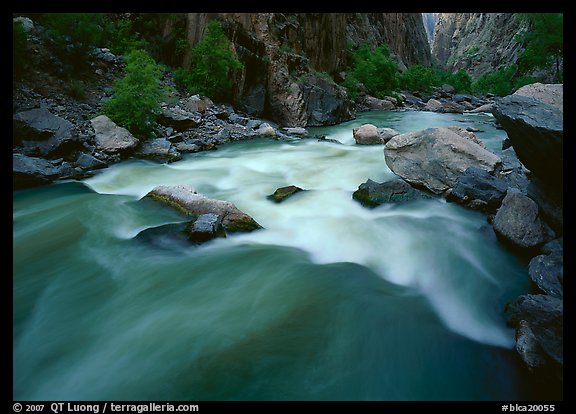

Unlike other canyons in the Southwest which were carved into soft rock, extremely hard metamorphic rock form the walls of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Combined with the steep descent of the Gunnison River (43 feet per mile, versus 8 feet per mile for the Colorado in the Grand Canyon), this has created a canyon with a unique combination of depth (2000 feet) and narrowness (1200 feet from the two rims, 40 feet at the river at the narrowest point).

Both rims of the Black Canyon feature numerous overlooks, each with their own character. After touring them, my favorites were either those with rectilinear views of the Canyon which help show its depth, or those close to the Painted Wall, the highest cliff in Colorado, 2250 feet high. In early May, on the less developped North Rim, I just saw a few other visitors.

Although I am used to exposure on sheer cliffs, standing at the edge often made me feel slightly dizzy. Such is the verticality of the canyon. Each of those overlooks were spectacular, but I also wanted to experience that verticality more directly by hiking down to the river and to look for a more unusual view. The Park Service warns that hiking the inner canyon is a wilderness experience, with “extremely difficult, steep, and unmarked routes”. They require a wilderness use permit even for day trips. Since the North Rim Ranger Station was still closed for the season, I just filled-up a self-registration form.

After parking at the Balanced Rock Overlook, I found the descent for the Long Draw route walking northeast to the bend in the road. Past a small area of trees at the rim, the gully to the river became quickly very steep with a vertical drop of 1800 feet in only a mile. Although there was no trail, the route was obvious, as it followed the narrow gully. However, because the terrain was rather treacherous, with loose rock and a few short ledges to downclimb, it took me an hour and half to cover the short distance.

The canyon is so deep and narrow that the sun reaches the bottom only during a short window of time around noon. For most of the day, the walls remain in the shade, which make the canyon look “black”. I made only a few stops for photos, as I planned to take more time on the way up, and try not to miss the window of light. The walls kept looming above more and more, and the sound of the river grew louder.

I reached the swiftly-moving river. The feeling of wilderness was intense, as I hadn’t seen anyone since leaving the road. The position, next to the roaring river, below the towering cliffs, was awe-inspiring. Yet although I had chosen the Long Draw route (without speaking to a ranger) because it looked like it went down into one of the narrowest parts of the canyon, I couldn’t find a composition that conveyed this sense of a very narrow and deep gorge. I thought that this was because from where I was standing, the opposite canyon walls did not overlap enough, but the terrain limited the possibilities to move around. Instead, I emphasized the river in my photographs, both upstream and downstream, trying compositions with and without the sky.

On this hike, I was using for the first time a lighter and smaller Gitzo series 1 tripod, instead of the series 2 that I normally carry. Although it provided adequate support even for the 5×7 camera, I wasn’t too pleased about its shorter height and smaller footprint. It turns out this was the last time I would use it. Getting ready for the hike up, I strapped the tripod to my backpack and shouldered it. The tripod flew instantly down into the raging rapids. Being shorter than the one I normally use, it wasn’t well secured with my normal strap. I didn’t even think for a moment about trying to retrieve it.

It happened so fast I didn’t have time to regret the expensive piece of equipment. However I regretted not being able to photograph some of the compositions I had spotted on the way down. I was eager to get back to my car – and the other tripod, without which my heavy large format camera was useless. Climbing up without stopping, I made it back in less time than it took me to go down.

From a photography point of view, the hike was not as successful as I had hoped, but I was happy to have experienced the inner canyon. As a few ray of lights began to shine from holes in the dark storm clouds, I hurried back to the Narrows Views overlook. The river, so mighty just two hours ago, now looked so small viewed from the rim.

View more images of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

View more River Level images of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park