Renewed Threats on National Monuments

8 Comments

Last week, I marked the 26th anniversary of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument by highlighting two sites along the Cottonwood Canyon Road. One of them, Yellow Rock, was part of the lands that lost protections when the former president reduced the size of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument by half in 2017. On October 8, 2021, President Biden reversed those size reductions and the more drastic size reductions of Bears Ears National Monument. It appeared as if with that action, the attack on the national monuments was no longer a newsworthy story, partly explaining the lack of interest from the mainstream press for Our National Monuments. The afterword of the book includes those words:

the battle for conservation will go on endlessly. We can no longer take designations for granted.

Protecting the land and its native people?

Today is National Public Lands Day when we have an opportunity to show appreciation for our public lands. I thought it an appropriate day to comment on the way that Utah Republicans cherish our public lands. Exactly a month ago, on August 24, the state of Utah and two of its counties, Kane and Garfield Counties, which contain Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Utah (complete text of the complaint). They expressed concerns for the land:87. Presidents now deploy the [Antiquities] act to shut down harmless local activity … by appearing to protect things that they are actually making more vulnerable. 99. Although a proclamation of a national monument does little to serve conservationist goals, it has enormous adverse effects for the antiquities themselves. 100. [A national monument] obstructs the very people who had long preserved and protected and loved that land from doing the things that are compatible with and beneficial to it—and that have kept and preserved the land and its resident archaeological and cultural features as they are today.

They expressed concerns not only about the harmful effect of the national monuments on the land, but also that “proclamations harm Native American interests”. Here is an example of their logic:

Many of the Navajos who live in the area … rely on collected deadwood, as they have for centuries, to stay warm through the Utah winter. They use existing roads and drive motorized or mechanized vehicles on reservation [meaning national monuments] land to access and transport this firewood. The proclamations also prohibit the creation of additional roads or trails designated for motorized vehicle use unless for public safety purposes or for protecting monument objects, and prohibit the use of motorized and mechanized vehicle use except on designated trails. Therefore, the reservations limit and perhaps altogether ban the Native Americans’ traditional use of these resources.They mention that “Support for the reservations among Native Americans is mixed” (as any reasonable person would expect) but do not elaborate on the composition of the mix.

The vision for the monuments from native people

It is well-known that Bears Ears was the first national monument initiated and co-managed by a coalition of native tribal nations. It is less known that up until 2018, Utah Republicans constantly quoted the San Juan County Commission, but abruptly stopped doing so after 2018. What had happened? In 2017, a judge recognized that the district boundaries amounted to racial gerrymandering and ordered San Juan County to redraw them. For the first time, Native Americans, who comprise about two-thirds of the county’s population, held the majority on the San Juan County Commission. Although it contains Bears Ears National Monument, San Juan County didn’t join the lawsuit. By the way, the sitting county commissioners had tried to get Willie Grayeyes removed from the ballot. Here is an excerpt from the essay by Utah Diné Bikéyah leaders introducing Bears Ears National Monument in Our National Monuments:At the outset, UDB’s founding Board Chairman, Willie Grayeyes, established the purpose of Bears Ears National Monument as a place of healing, where we are each invited “to heal the land and its people.” Willie advises each of us to look deeper into ourselves. “Healing,” he says, is first rooted in our spirituality, and it has essential “psychological, physiological, and social components.”The vision of the native tribal nations for Bears Ears National Monument is developed in the informative Collaborative Land Management Plan for the Bears Ears National Monument from the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (BEITC), which is an excellent read for anybody trying to learn more about this part of Utah. Their approach is holistic:

Any disruption to the natural world would negatively affect the viewshed, and by extension Native people whose spiritual power resides in that natural world. Any changes to that landscape that are done in a disrespectful manner negatively affect all people, the ecosystem, and all life forms. Such changes include mining, clear-cutting of timber, and creating roads in formerly roadless areas.Tribal Nations of the BEITC consider BENM to be a spiritual place and thus value the need for peace and quiet. Hopi people believe that the spirits of their ancestors still reside at BENM, and any disruption of peace will disturb them.

Air quality is considered to be a key component of health by the BEITC. Clean air is important because it is part of an overarching earth stewardship that is part of all Native traditions. Air pollution from mining and milling, machinery, vehicles, and construction are considered to damage or corrupt the natural environment.

There is consensus that the night sky in open spaces should be protected in order to preserve these ancestral connections. Light and dust pollution are factors that affect the quality of the night sky.

A landform may be part of an archaeological site, a shrine or an offering place, but it is a distinct geological or topographical feature that is imbued with cultural significance.

The vision for the monuments from Utah Republicans

The immediate goal of the Utah lawsuit is to seek the nullification of President Biden’s proclamation/restoration of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, returning both to the reduced boundaries in effect from Dec 2017 to October 2021.However, the authors go further in laying out their radical vision of what would be an appropriate application of the Antiquities Act. They see only a handful of sites within Grand Staircase Escalante as worthy of the act’s protections and estimate that less than 1% of the current monument area would be enough to protect those sites, as illustrated by the map below where

representations of lawful reservations are slightly larger than scale because accurate representations of lawful reservations would be practically invisible when compared to the current reservations.

Such small areas are justified because:

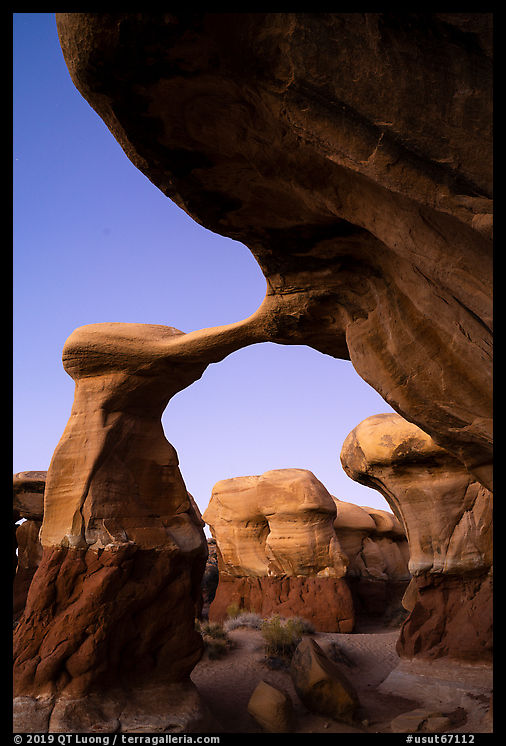

280. For the sorts of qualifying items that might be found within the reservations, the primary threat comes from direct human contact, which cannot be accomplished from more than a few feet away. 281. Activities that occur more than a few hundred yards away from any qualifying item are extremely unlikely to harm that item.In their view, Grosvenor Arch qualifies, and “a reservation of 40 acres would be more than sufficient”. They explicitly mention Yellow Rock in a list of sites that would not qualify because it is “nondescript” or “inconspicuous”. You can see for yourself photos and descriptions of Dry Fork of Coyote Gulch, Peek-a-boo Canyon, Zebra and Tunnel Slot Canyons, Wahweap Hoodoos, Toadstool Hoodoos, Upper Paria River complex, and Sunset Arch, which are on that list of non-qualified sites. The list also includes Devils Garden and Metate Arch whose photos illustrate this page.

At the heart of the issue

The Utah complaint makes several points deserving of consideration, such as the impact resulting from increased visitation linked to designation without appropriate appropriations or the ecological consequences of stricter land management regulations. Others are bizarre, for instance, the notion that cattle grazing has “ecological benefits”. Having seen the difference between grazed lands and ungrazed lands in the Sand Tank Mountains of Sonoran Desert National Monument, I tend to agree with the observations made by Jonathan Thompson in southern Utah that excluding cattle is beneficial to the land.

However, the main arguments are that the Antiquities Act does not allow the president to declare entire landscapes or generic items as qualifying “objects of historic or scientific interest” and that the establishment of the monuments violates the “smallest area compatible” provision of the Antiquities Act.

If this sounds like a deja vu, it is because we have already heard those arguments a long time ago. Arizona politicians tried to block President Theodore Roosevelt’s proclamation of the Grand Canyon as a national monument on account of its size, with Ralph H. Cameron arguing, in addition to mining claims, that it did not meet the “confined to the smallest area” standard, but in 1920, the Supreme Court rejected this argument and upheld the president’s decision. Wyoming politicians objected to the proclamation of Jackson Hole National Monument by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (with an eye towards an expansion of Grand Teton National Park) on account of its lack of qualifying objects, but in 1945, a district court in Sheridan, Wyoming also upheld it after hearing opposing expert witnesses testify on whether there were historic or scientific objects in the region. The state of Wyoming didn’t appeal, but instead, a compromise agreement was crafted between the state and the federal government.

Beyond the Utah monuments

It looks like Dobbs has paved the way for reconsidering precedents at the Supreme Court. The complaint specifically targets President Biden’s proclamations, but notes that he has ignored the limits of the Antiquities Act “like too many of his predecessors over the past hundred years”.It frequently quotes the views of Chief Justice Roberts back in 2021, including in their last argumentative paragraph. Commercial fishermen had contested the size of the 5,000-square-mile Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument proclaimed by President Obama. After losing their bid in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in 2019, they tried to take their case to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear it. However, according to the complaint:

95. Chief Justice Roberts wrote that expansive presidential reservations would not strike “a speaker of ordinary English” as lawful under the statutory text.96. He criticized the “trend of ever-expanding antiquities.” As he read the statutory text, the Reservation Provision’s smallest-area-compatible limit imposed a “unique constraint” that, due to unnaturally broad constructions of the Act, “has been transformed into a power without any discernible limit to set aside vast and amorphous expanses of terrain above and below the sea.”

97. He invited attention to the question of “how a monument of these proportions … can be justified under the Antiquities Act.”

98. Chief Justice Roberts was particularly concerned with two issues: (1) “[t]he scope of the objects that can be designated under the Act” and (2) “how to measure the area necessary for their proper care and management.”

Chief Justice Roberts had mentioned in 2021 that the Supreme court might get another chance to rule on that question as there are “five other cases pending in federal courts concerning the boundaries of other national monuments.” The Utah Republicans seem to be hoping that the Supreme Court will take this case.

Rising the stakes beyond the Utah monuments, the complaint argues that the Antiquities Act itself is outdated and made unnecessary by more recent and specific laws. Will the shifting political winds at the Supreme Court undermine the venerable law itself? If we go by the surface area of protected lands, the Antiquities Act could be seen as the most important conservation law in America, responsible for its boldest conservation advances. If its language proves too narrow in an age that is more ecologically minded and subject to unprecedented environmental threats, will Congress enact an update?

The sheer effrontery of the lawsuit is mind boggling. “shut down harmless local activity … by appearing to protect things that they are actually making more vulnerable”? The pillage and destruction of antiquities by those harmless locals is legendary, and they have the gall to assert they they’re the proper protectors? A few acres to “preserve” Grosvenor Arch? Spare me.

One can only hope the courts throw out this reality-challenged garbage on it’s face.

Sorry for the rant. It’s really not my style, especially in a blog like this, but I have steam coming out of my ears.

Thanks for the comments. The actions that precipitated the enactment of the Antiquities Act were those of a Swedish man, Gustaf Nordenskiöld, but he was hosted by the no-less controversial Wetherills who were local Colorado ranchers. The authors of the complaint would consider Grosvenor Arch unharmed even If you had to cross a forest of pumpjacks or derricks to reach it, as long as the closest of them would be a few hundred yards away.

I find this purported concern for the land from the Republicans distasteful.

We all know what they stand for. At least the Trump reductions in size didn’t try to obscure their intention to develop the lands for extractive industries. My understanding is that there are a lot of coal reserves in Grand-Staircase Escalante National Monument?

That’s right. There are vast reserves of coal below the Kaiparowitz Plateau, and they have long been eyed by the industry. It could be that the authors recognize that the idea of burning coal nowadays sounds a bit retrograde, so they put it that way:

Thank you for updating us on the fight over Grand Staircase-Escalante. I think the monument is special not only because of its unique areas but also its amazingly vast size, and I would hate to see it diminished in the ways the lawsuit seems to suggest. Do you know if the matter is open to public comment or if there is some other way we can help to preserve the monument?

I doesn’t look like public comments are sought for GSE, since it is a matter of litigation – not that public comments made a difference when 97% supported GSE and it was reduced anyways. On the other hand, federal agencies are seeking comments on their management plan for Bears Ears. I submitted a comment to the effect that they must make sure that tribal expertise and traditional knowledge informs the monument’s management – in practice meaning collaboration with the BEIT.

https://www.blm.gov/press-release/blm-and-usda-forest-service-begin-new-land-use-planning-process-bears-ears-national

The history of the USA has always been about money. The destruction of the plains for large-scale farming; the destruction of great forests for lumber; the ruination of water supplies by mining; the depletion of aquifers for water; the list goes on — all done to make wealthy men even more wealthy. And it never stops, because greed never takes a holiday. Like democracy, our natural resources will always be under attack by those who only care about money. We have to recognize that the attacks will be relentless and settle in for a “forever struggle” to protect our heritage, whether that be democracy or our natural resources.

For sure, there are undesirable consequences of capitalism. But the USA also invented the national parks. One thing that struck me in “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea” was how some of the wealthy contributed so much money and energy to establish parks. In fact, in the series, the wealthy play an outsize role both as forces for and against protection. Money talks loudly!