(original image)

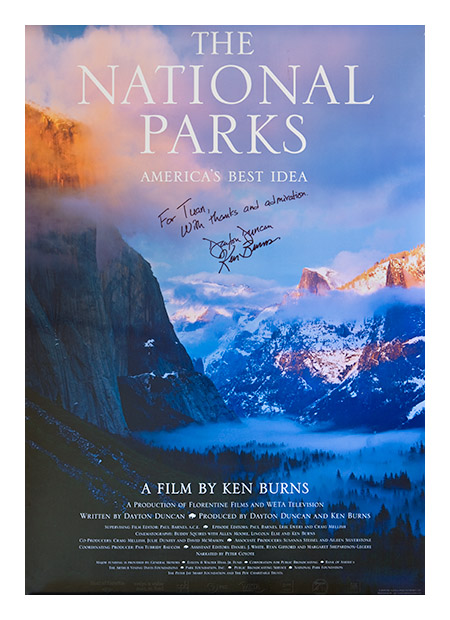

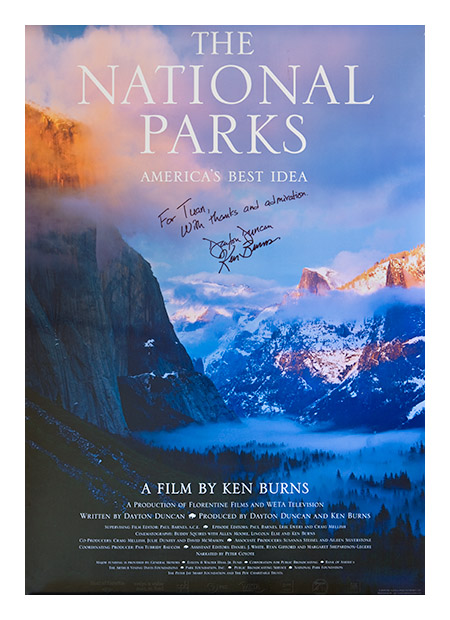

Ken Burns doesn’t need an introduction, especially from me. Unlike most everyone who begins his speech this way, I will actually not provide one, but instead focus on his new film, The National Parks, America’s Best Idea, and my small part in it. The film is coming to PBS in exactly a month, between September 27 and October 2, two hours a night. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

I first saw previews of the film in San Francisco in April this year. In May, I was invited to Mountainfilm in Telluride, where I exhibited a dozen of images and participated in a joint Q&A session with Ken Burns. I had the pleasure to share a suite with Shelton Johnson, a Yosemite NP ranger with such a great personality, voice, and insight that he appears in each of the six episodes of the film. During the festival, where the “The National Parks, America’s Best Idea” premiered, I saw the entire 12 hours of the film.

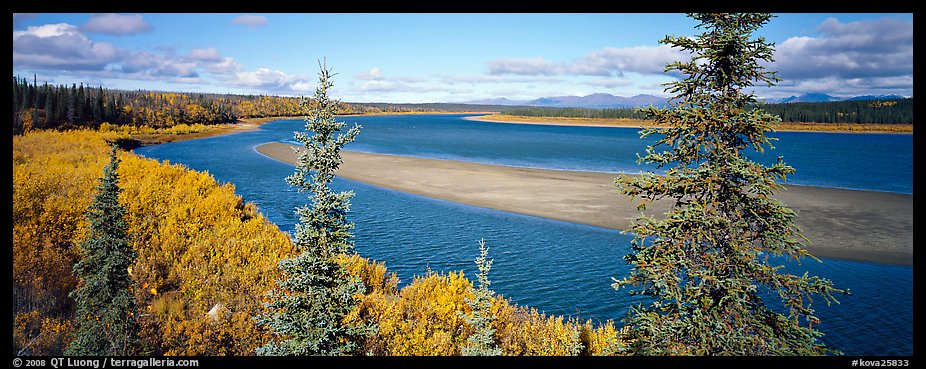

The beautiful cinematography was a treat on the large screen, all the more enjoyable because I was able to recognize most locations. However, the focus of the film was not on the scenery, but on the human history. Like all the previous Ken Burns series, the film chronicles an important aspect of American history and invention. It is a story of democracy in action, through a uniquely American idea: that the most special places in the country should be preserved, not for some privileged people, but for everyone.

I learned so much about the dramatic struggles and historical characters who made the National Parks possible. They ranged from icons such as John Muir, whose remarkable story is told in great detail, to a score of people whose name I hadn’t heard before, in spite of their importance to the National Parks. For instance, before George Melendez Wright undertook his studies, it was an official policy to feed garbage to the Yellowstone bears in front of tourists.

Most unexpectedly, I was very moved, often to tears, by several episodes. It is a absolutely compelling story, marvelously told.

As photography had, from the start, played an important role in helping the parks get establish, many photographers are featured in the film, incidently all of them working in large format. William Henry Jackson’s photographs helped convince people back East that the wonders of Yellowstone were real. The Kolb Brothers pioneered photography in the Grand Canyon. George Masa, a Japanese immigrant, was instrumental in the founding of The Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the mapping and building of the Appalachian Trail. Ansel Adams took the images that convinced FD Roosevelt to approve Kings Canyon National Park – although FDR knew that he would never personally get to see those scenes himself. To this effect, Ansel sent a portfolio to the secretary of the interior, who showed it to FDR. However, FDR decided to keep the portfolio for himself. Ansel Adams was subsequently hired to photograph each of the National Parks. At that time, there were only about 25 of them, but he missed one. Almost last, Bradford Washburn, used large format aerial photography to map Denali and then pioneer a new climbing route to the summit. His appearance on camera was particularly moving, as he has since passed away.

As the Parks themselves are characters in the film, Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan undertook an extensive location filming program, taking them to 53 of the 58 Parks. In the course of researching those locations, they found my National Parks gallery. At that time, I had already visited each of the 58 National Parks, and my website offered a wealth and quality of images of the Parks not available anywhere else, including on the National Park Service website. Many people have written to me to tell me how the images have helped them plan their visits. Much in the same way, the film crew used them to help plan their production.

Subsequently, they became interested in using images to fill missing sequences in their cinematography, as well as to illustrate the companion book since they had only movie footage that does not print as well as still images. In the process of conversations, they became intrigued by the story of my life, which had been changed so much by my project. That would be a subject for another post, but in short it was my involvement with the parks that inspired me to make my home in America, and eventually quit a noted career in Artificial Intelligence to become a full time photographer. My project to photograph all the National Parks, despite the daunting task of lugging a 5×7 inch large format camera anywhere, had been accomplished in the most “democratic” fashion, self-financed, often alone, with no more support than any ordinary visitor to the parks in their own travels.

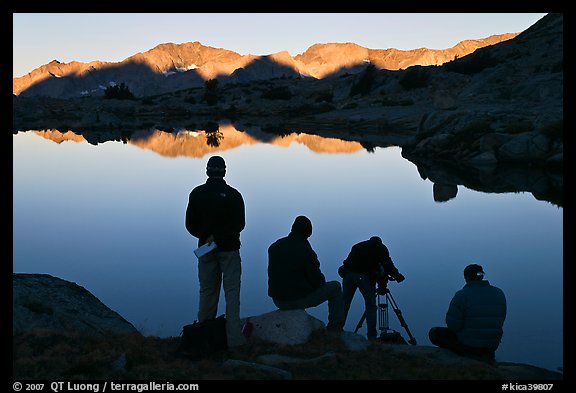

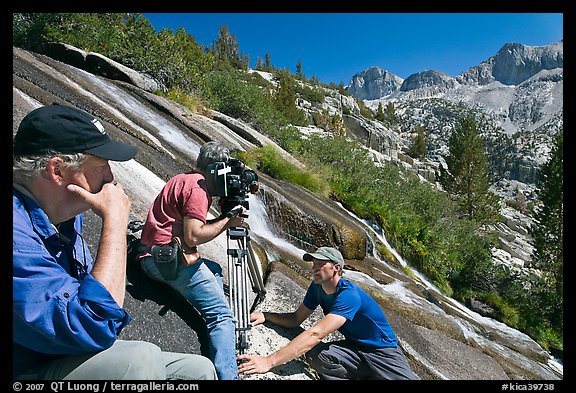

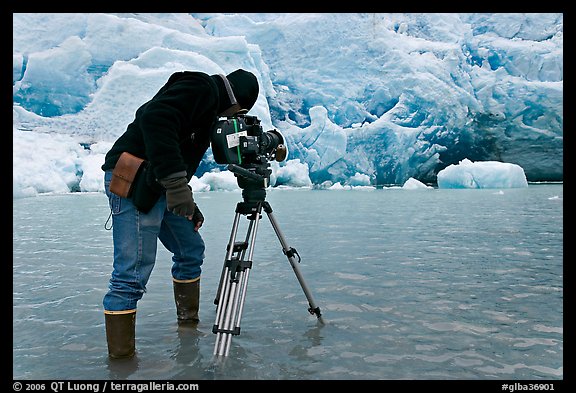

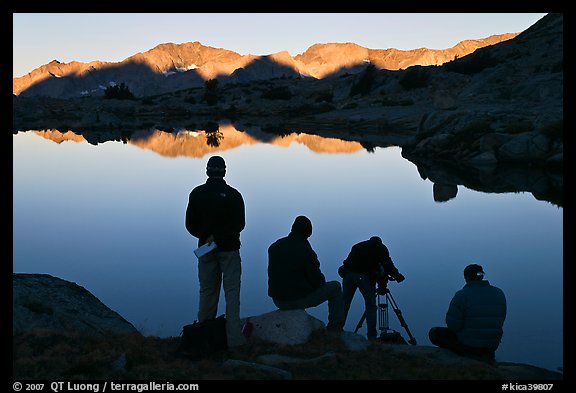

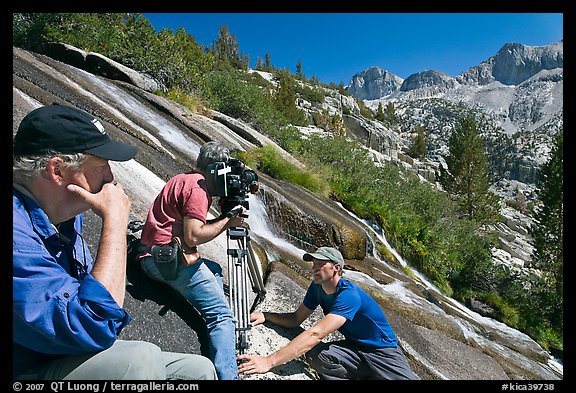

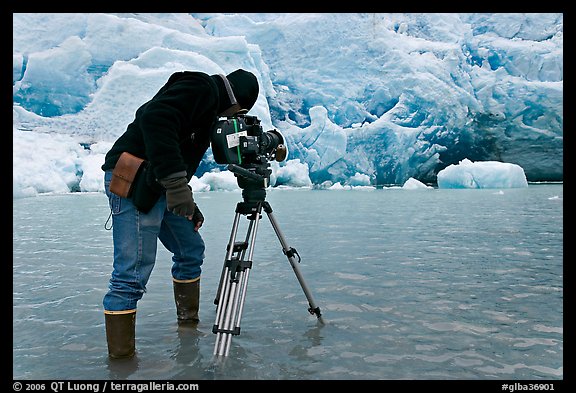

Dayton Duncan invited me to join their crew on location, which I did twice. In Glacier Bay National Park, a boat was chartered. In Kings Canyon National Park, a pack of mules helped to transport the gear. It was interesting to see how a film crew worked, and to compare the different operating modes of a cinematographer and a photographer. They would look for views where panning adds interest by revealing features that were not visible at the beginning of the sequence. They would notice and try to capture even the most subtle motions, such as the shimmer of water on a Iake, or grasses swaying in the wind. There were similarities, too, besides getting up one our before sunrise. Their hefty tripod reminded me of my first Zone VI wooden tripod (a modified surveyor’s tripod). They even used a changing bag on location to load and unload film rolls. For those not familiar with large format photography, that’s a lightproofed bag with holes for your arms that you use as a “portable darkroom”.

They filmed a sequence of me working on location in Glacier Bay National Park. Previously, Ken Burns had interviewed me in San Francisco for the film. Knowing all his achievements, I was initially quite intimidated on that occasion, so it was a surprise to see how young he looked, and how friendly he was.

I felt very honored to be one of the few living characters featured in the film. From the beginning, I had sought to raise awareness and respect for those treasured lands, a goal I felt I shared with the makers of the film. Part of episode 4, you can see the short segment where I appear on the PBS site. When I saw the film segment in May, I was shocked to hear my thick French accent. I knew that sometimes people had difficulties to understand what I was saying, but that was the first time since becoming an adult that I saw myself on any footage!

Update: Check this post for a more recent link to the clip.