Summary: One of the photographer’s greatest fears is to lose a significant chunk of images from a big trip or event. In this long-form article, find out how a memory card failure caused a week of photographs to disappear, what I did to try to recover them via software, then physical data services, and the valuable lessons, counter to common knowledge, to be learned about memory cards, dual card slots, and backups to prevent such a nightmare scenario from happening to you.

Landscape expeditions can be taxing in the long days of summer, even more so if

you are also doing night photography. After flying to Seattle, I arrived at the coast of Olympic National Park around

11 PM – many view Treasured Lands as a culmination of my work in the

national parks, but I am far from being done with them! Seeking stars, I woke up before 2 AM for the short window between moonset and astronomical twilight. However,

the marine layer had rolled in while I was hiking to the beach, and I shivered until past sunrise time without even seeing a sliver of sky. The next day, since I had to drive from Heart of the Hills Campground and hike 45 minutes to Hurricane Hill, I rose before 1 AM.

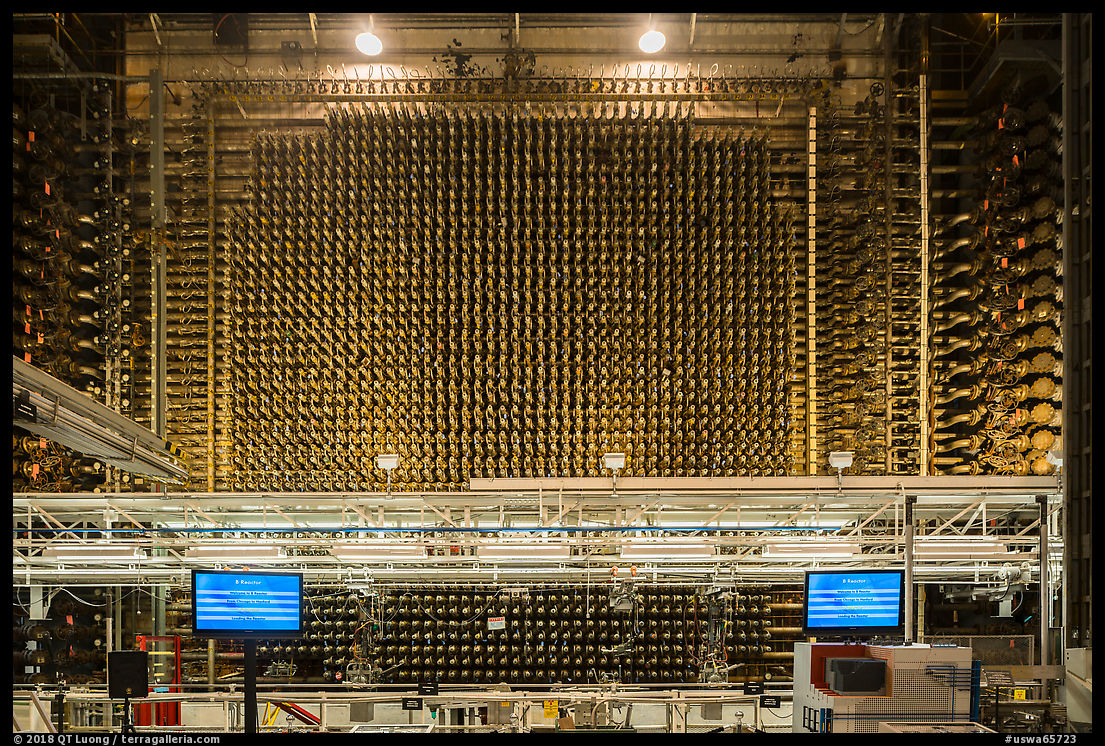

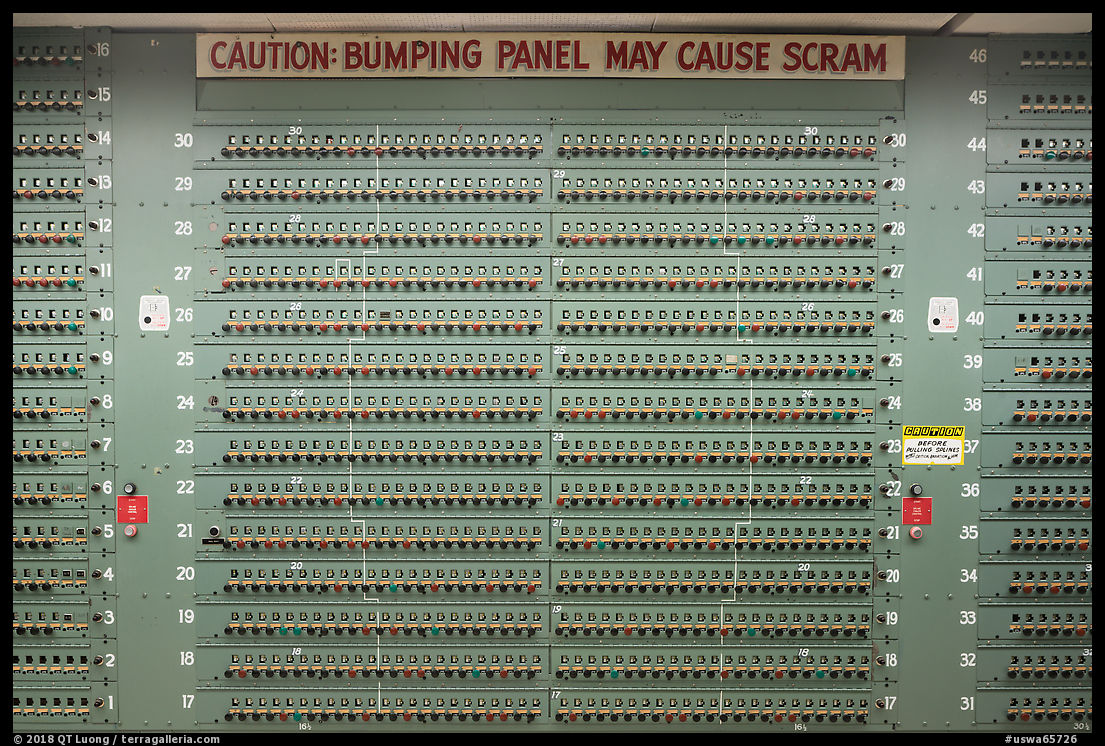

On the last day, temperatures in the inland plains of Hanford Reach rose above 100F.

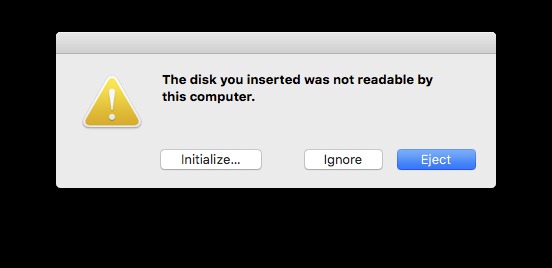

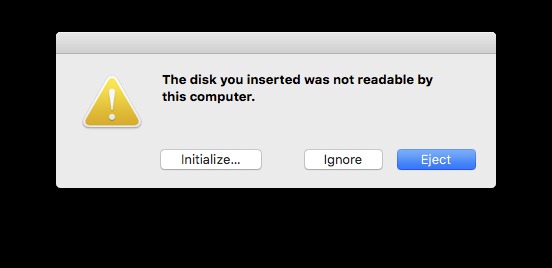

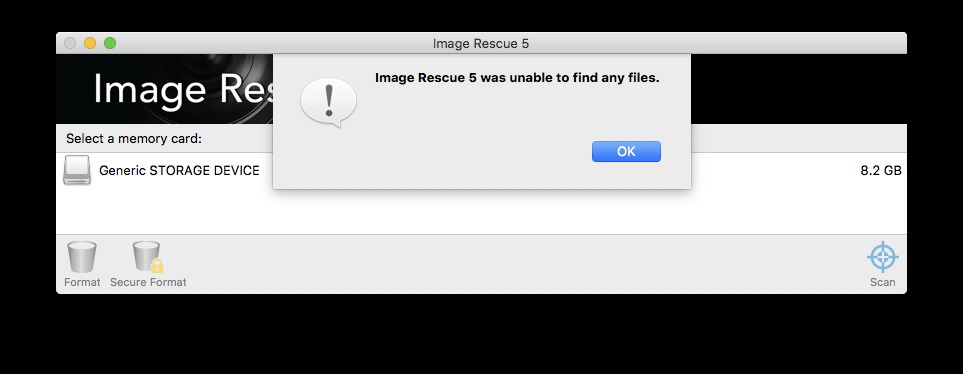

When I came home from the week-long trip, I went straight to bed. The next morning, I reached for my cameras, took the memory card out, and inserted into the card reader. This resulted in the dreaded:

Attempting to read the card with software

I reacted with mere annoyance at the computer, and tried to read the card from the built-in memory card slot of a laptop. The same message appeared. Growing worried, I inserted the card into a standalone backup device, and it said “Memory card not found”. Surely I would be able to see the files in the camera, since the last time it had been turned on, less than a day before, everything was normal and I was able to scroll through some images? Nope, like the computer, the camera said “Unable to use memory card. Format?”

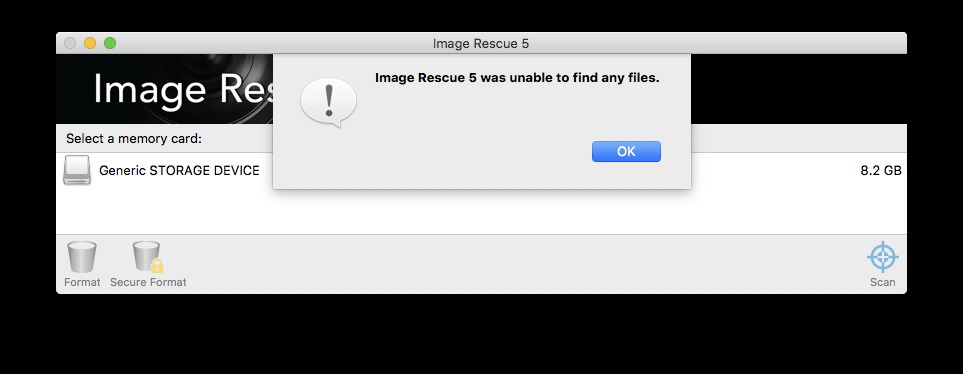

The PhotoRescue software installed on my computer had been successful at rescuing files from a corrupted card in the past, however, it did not uncover a single file this time. Hoping for better luck with Lexar’s own Image Rescue software that came with the card, without the activation code handy, I contacted Lexar’s customer support. They were quick in providing me a download, but it did not help:

Note that the computer sees 8.2 GB, but it was a 64 GB card. Lexar support suggested several other apps, including Ontrack® EasyRecovery which has a “technician” version with a $500/year licensing cost. As those apps include a trial mode that allow you to attempt to discover files, and require you to pay the fee only to actually recover them, I took each of them for a spin without success. There are a lot of recovery programs around, but if the error is hardware rather than software, you can try all the programs in the world, and they won’t do you any good.

Dealing with physical data recoveries services

It was time to contact a physical data recovery company. All those companies have a similar mode of operation. You send them your media with pre-paid overnight shipping at their cost, they diagnose it and provide an estimate. If you approve the estimate, they attempt to recover files and charge you if the recovery is successful. Seems fair, right? The problem was that the quote from the Lexar-recommended company was quite a bit higher than I expected:

After a bit of shopping, I found another company which provided me a lower quote. I sent them the card via Fedex overnight and got the following diagnosis:

Despite numerous attempts to identify the source of the problem, we were unsuccessful in reaching a solution. At this stage it is clear that this is an extremely complex case that will require extensive research, time & use of in-house donor parts. Your media will be passed to our Research and Development department; They will be able to research & execute techniques such as safe removal, reballing and replacement of the core processor and other components containing device specific information and repairs to fractures in the tracks of the logic board.

The work we would attempt is a highly skilled process that is not infallible. The chance of a successful recovery once these processes are completed is approximately 74%. At this point most Data Recovery services would send the media back to you as they don’t have the ability to do such complex work, let alone any sort of R&D department. Our R&D department is one of the best in the world, and they are responsible for creating new techniques and ways of recovering data that allow us to sustain an overall 92% recovery rate. Currently, we have two options for you:

Option 1.

You allow our R&D department to use the lab time, parts & cleanroom facilities needed to gain access to your data. This is a standard process that will be completed within 15-20 business days.

To go ahead with Option 1 an upfront payment of $800.00 is required, and this covers everything the R&D department will need to provide you with feedback: all lab time, parts required from our library, and cleanroom usage. If we are unable to gain access to any of your data that initial fee is not refundable.

Option 2.

We return your media to you via either our courier or standard option, and you incur no recovery costs as we were unable to recover your data.

Although the fee wasn’t too bad, I wasn’t going to pay upfront without a recovery guarantee, especially after my friend Tommy, a technology entrepreneur and all-around geek opined “These are extremely difficult and risky techniques. I’m skeptical that they have such capability and even if they do, I doubt that the success rate is 74%. I guess more like 25% or less”. I declined, received my media back a few weeks later via regular mail, and sent it to yet another data recovery company:

Would you have proceeded with the recovery at this price?

Although you don’t often read that in reviews, my main complaint with the

Sony A7R2 cameras is sensor dust resulting from the mirrorless design and an ineffective sensor dust cleaning

system – it mechanically shakes the sensor using the image stabilization actuators.

To cope, I work with two camera bodies in order to minimize lens changes.

The excellent 24-105 FE (review) stays on the primary

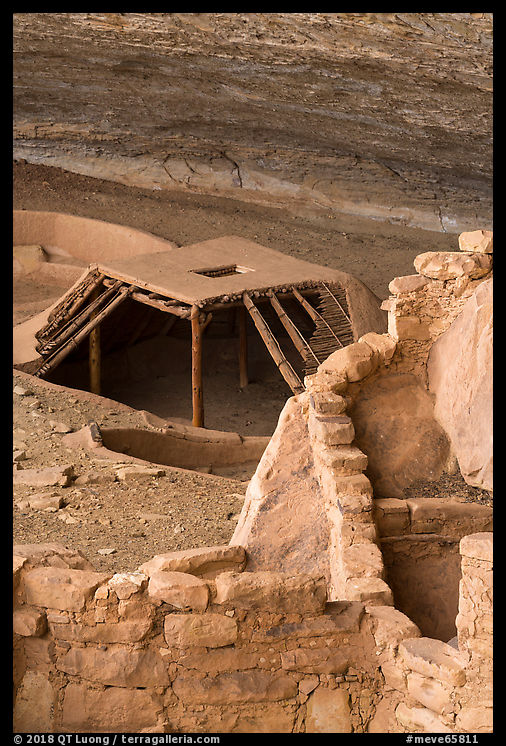

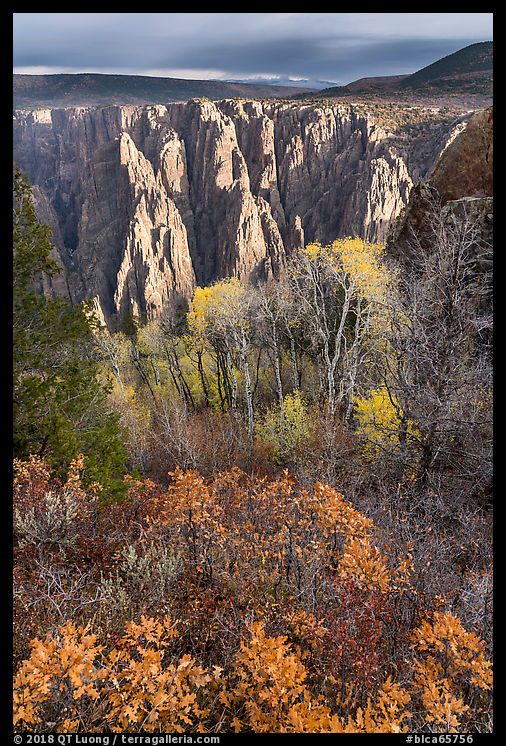

camera which is used for most of the photographs, while I reach for the secondary camera when I need more specialized lenses. On that trip, I had failed to do drive backups and the damaged memory card was in the primary camera, which meant that it contained the majority of a week’s worth of work, and probably the best photographs. However, I retained usable images from the second camera, a few of which illustrate this post.

I decided against proceeding with the attempted recovery, saving me the potential disappointment of failure or costs. It is not that the pictures aren’t worth the amount asked. Rather, including all expenses, the trip cost me only a fraction of that amount. This math didn’t account for my time, but no matter how tiring the effort felt, that time was spent on a process that I largely enjoy. Losing the pictures did not rob me of the experiences I had nor of the scouting I did, and rather than looking back by investing in the recovery, I chose to look forward by saving the money for a repeat trip – and a new camera.

The larger conclusion here is that attempts to read a card with recovery software may not always work, physical recovery services are expensive, and also not guaranteed to work. Even after three decades in photography, the incident reinforced several lessons for me.

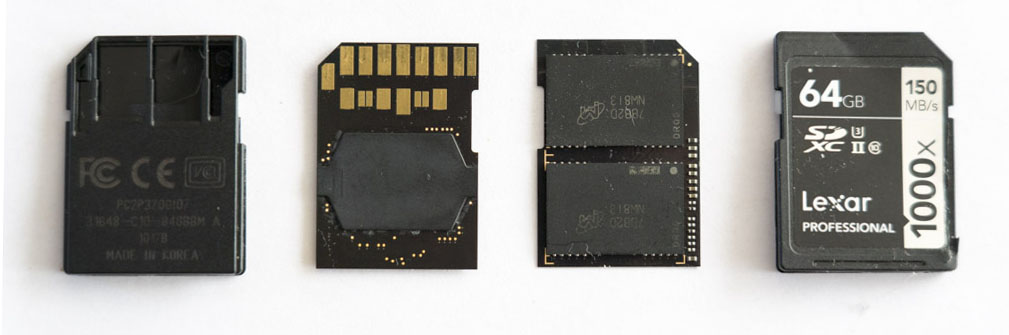

Memory cards can fail

The disaster drew home the point that memory cards do fail catastrophically. Both data companies found serious physical damage, but that was a card that had been moderately used for a year without any single glitch, so neither “dead on arrival” nor past any reasonable life expectancy – which by the way nowadays is longer than technological obsolescence. It had never been subjected to any form of abuse before as it spent most of its life in a single camera, was formatted after each download, and prior to failure went straight from the camera to a card reader. There were certainly no warnings nor reasonable explanations.

I have been using digital cameras since the first days of full-frame in the early 2000s (remember the $8,000 Canon 1Ds series?) without any card failure, while during that time, I have had to replace a half-dozen failed hard drives. This made me overconfident in flash technology.

If you browse the internet, you will see that I was far from being alone. Quite a few other professional photographers (some with scores of workshop clients) state that they have never experienced any card failure and that when it happened, they were always able to rescue images with recovery software.

Clearly, my experience has been different.

The fact that you’ve been lucky doesn’t mean that your luck won’t run out at some point, as it did for me – and others. As we will see next, a quick perusal of customer reviews shows that memory card failure is not that rare.

Cards are not equally reliable

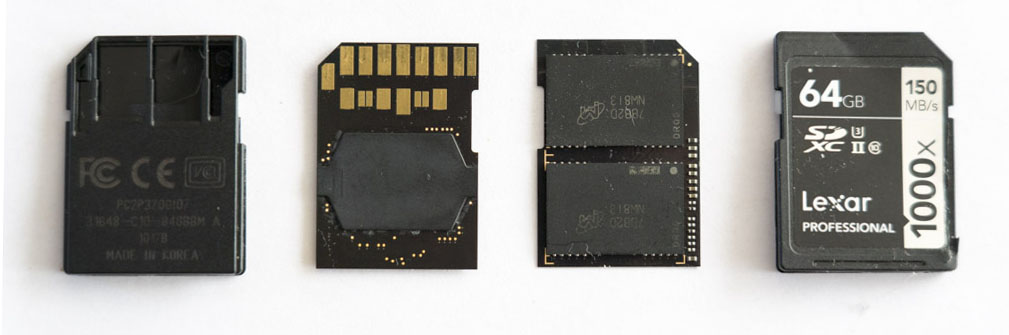

The card that failed is a

Lexar Professional 1000x 64GB SDXC

UHS-II/U3, which is amongst Lexar’s top line of cards, and deemed “professional” by the manufacturer. I used to

believe that any memory card from a reputable brand would be reliable. If in addition, you bought it from a reputable vendor, chances that you’d get a counterfeit of questionable reliability would also be low.

The preferred vendors are specialist stores such as

B&H, but Amazon is fine, as long as you don’t buy from their third-party merchants.

Sandisk and

Lexar are two of the most well-known brands, and I’ve used exclusively their cards, depending on the best deal I could find at the moment.

Because of that belief, I didn’t pay much attention to customer reviews, adopting the attitude that nothing is 100% foolproof and unlucky folks can have a bad experience with any product. Besides, a quick glance at the ratings show that almost all cards are rated between 4-stars and 4.5-stars, so they must be good products, right?

It would have done me more good to read the Amazon customer reviews before buying the card, but after the card failure, I looked them up. One of the first 1-star reviews I read described the exact same experience I had:

I literally had just reviewed the pics on my Nikon D610 camera and inserted the card into my card reader and got a message that it was not formatted (which it was – I format every card when it’s new). I put the card back into my camera – and same Format error.

Although I didn’t read all the 300 1-star reviews, the ones that I sampled overwhelmingly bemoaned card failure.

Since this was becoming quite relevant, I looked at the 1-star review tally: 15%. That’s almost 1 out of 6 reviews, odds similar to the Russian Roulette. If someone killed themselves playing the game, I don’t think you’d attribute his death to “just bad luck”. Of course, this is not a scientific observation because several factors affect review-writing, but you get the idea. On the other hand, it is instructive to compare the percentage of 1-star reviews for a few other UHS-II cards:

If we assume that 1-star reviews are exactly the type you’d leave if the card totally failed, from that small sample, we can see that some cards are four times more likely to fail than others. This data also sugggests that there is a problem with those UHS-II Lexar cards. On the other hand, the

Lexar UHS-I card that I have used for several years gets a convincingly low 3% of 1-star reviews. The lesson here is that not all cards are equal, even amongst those from a top brand. And if they can have such a high failure rate, think about cards from less reputable or conterfeit brands! By the way, looking at those numbers also indicate that failure rate with SD cards is far higher than CF cards.

Pay attention to negative customer reviews

Some negative customer reviews are frivolous because they are rooted in user error, or because

they concern themselves with delivery rather than the product’s

quality or performance. However, negative reviews are generally more

significant than positive reviews.

If you think that one shouldn’t

focus on the negative while the vast majority of reviews are positive,

consider that on Amazon, the average rating for a product is 4.4 (out

of 5) as found

here by analyzing 7 million reviews. Even

a product with an average 4.0 rating (4-star) is below average. The

large majority of products are rated above 4.0, so the difference

between a great product and a subpar product is less than 1 (star) on

average. On the other hand, we’ve just seen that the number of 1-star

reviews for different cards varies by a factor of four.

Consider dual card slot for backup

If your camera has dual memory slots, the most obvious and foolproof way to prevent data loss

from memory card failure is to set the camera to write to two cards simultaneously so

that it creates a back up in real time. Now that memory card have become very affordable,

you can buy two sets of cards with enough capacity to last you for your whole trip so you don’t have to

reuse any card, and you always keep two datasets.

Dual memory card slots are standard in high-end DSLRs cameras, and after

omitting them in their first two generations of mirrorless cameras,

Sony has started providing them in the A9 and A7 mk3 series (a good example of listening to customers, since there were complaints about the single-slots in previous cameras, many of them from Canon and Nikon users), with the caveat that the second slot is UHS-I,

so using simultaneous writing will negate the benefits of the faster UHS-II main slot. I was thinking of

skipping the A7R3 generation and wait for the inevitable A7R4, but the incident prompted me to upgrade.

Recently announced full-frame mirrorless cameras from Canon and

Nikon have been greeted with an inordinate number of Internet comments about

their single memory card slot. We saw many claims that no professional would use cameras with a single memory slot.

But the fact is that some professional photographers refuse to use the second slot for back up even when their camera has one, and for specific reasons. To start with, when I was shooting the Canon 1Ds series, I did not set up the cameras to simultaneous write, possibly because the size of the memory cards available back then made it mandatory to perform daily backups. More recently,

Lloyd Chambers uses his dual-slot Nikon as single slot SD cameras because he is annoyed

by the camera defaulting to the wrong card – this reminds me of Ted Orland’s aphorism “Owning more than one lens assures that you will always have the wrong lens on the camera for any given picture” – while Thom Hogan

uses his dual slot Nikon as a single slot XQD camera because the SD slot slows down the camera.

Colby Brown thinks that “there is no point in making two copies of your SD cards” and accordingly

sets his Sony A7R3 to auto switch as he estimates he has a higher chance of missing a shot because of a full card than a SD card failure – what I used to do with the 1Ds.

I wonder if those statements about the rarity of card failures do a disservice to less experienced folks, because what isn’t

clearly disclosed is that, although those photographers apparently don’t fear card failure, they also have extensive backup strategies using hard drives.

Have a solid backup strategy

If there is one thing that I wish others learn from my misfortune, it is that a solid backup plan is necessary. You want multiple copies of your data in multiple places. There are quite a few ways to go about it.

Several brands now offer ruggedized portable drives. SSDs, which have fallen in price, are much less prone to damage than HDDs. Using drives for backups, you can do a daily (or even more frequent) backup, and have more than two copies of your data.

On the other hand, compared to the in-camera dual slots backups, drive backups are not in real-time, so you could possibly lose a day of data. More importantly, you need to remember and take the time

to perform the backups – when maybe you’d just rather go to sleep. During that ill-fated trip, I carried a portable drive, yet due to a combination of fatigue, loaded schedule and complacency, I did not use it. Another reason was that my portable drive had experienced a glitch during the previous trip, forcing me to skip backups, which in turn broke my habit of making them regularly. This brings up the point that with drive-based backups, you have to carry more gear, which could also fail. Even if you carry several USB external drives, you still depend on your laptop for your ability to make drive backups.

With in-camera dual-slot backups, given the availability of huge capacity cards, you could shoot most trips on a single pair of cards, but if something catastrophic happened to your camera, you’d lose everything. Alternatively, you could use smaller cards, and once a pair of card is filled-up (or another threshold in capacity or time is reached), each of them can be stored at an independent location to minimize the risk of loss due to theft. While the second approach increases the chances of a problem because you have more cards to manage, it minimizes the adverse effects of problems.

For now, I have settled on an approach which I think provides me the most redundancy with the least effort: use the second slot of the A7R3 for real-time backup with a medium-sized card, plus do a daily backup on a single self-contained portable hard drive. My choice is the

HyperDrive ColorSpace UDMA3 that I fit with a SSD drive. I generally prefer such a device to a laptop because they are considerably smaller and much faster to deploy for backup.

Eventually, my data loss was caused by my own neglect. I let my guard down and did only a few trips without backing up, and see what happened.

This is just my experience and one data point, but I hope it’s been useful to you to read about it. What is your backup strategy? Did you experience a catastrophic memory card failure that you’d like to share?