For a reaction to the October presentation of the actual camera please scroll down.

Last week’s news has been the announcement by Lytro of the upcoming launch (later this year) of the first light field camera. I normally don’t write about new technological developments, but this one has the potential to alter photography as we know it. As a former award-winning imaging researcher turned full-time photographer, I couldn’t resist commenting. Please correct me if I got anything wrong.

The light field is a fundamental concept in imaging. It describes the amount of light traveling in every direction through every point in space. Whereas conventional camera sensors record only the sum of the color/intensity of rays of light falling on the sensor at each focal plane point (2D) a light field camera captures the color/intensity and direction of the rays of light (2D) falling on the sensor at each focal plane point (2D) – the “focal plane light field”, a 4D subset of the global light field. The additional information makes it possible to create images in a way which was not possible with existing cameras. In particular, Lytro emphasizes the ability to set up focus point as desired from light field files after the shot, much the same way you can set white balance and exposure (within a certain range) after the shot with RAW files.

While the light field concept has been known for a while (its name was coined in 1936) it was not until the mid 90s that it became extensively used in computer graphics, a subfield of computer science concerned with generating realistic images – for instance photographic images from light fields. The main practical limitation was that capturing the light field required cumbersome, specialized devices, such as the goniometer and multi-camera array from Stanford.

This changed with the graduate work of Ren Ng, Lytro’s founder: in his PhD thesis of 2006, he demonstrated light field capture using a microlens array between the sensor and main lens of an off-the shelf (medium format) DSLR.

Having seen less than a decade ago the previously mentioned room-sized devices, I am amazed that Lytro is set to release a compact light-field camera this year. This is an incredible technical achievement. However I note that the US press that has amplified Lytro’s press release last week has largely ignored the fact that there are already working light field cameras on the market, offered by Raytrix, a smaller company also founded by imaging researchers – they can even transform any digital camera into a light field camera by making a custom microlens array. I guess a German company targeting the industrial, scientific, and entertainment markets (with the high product prices to boot) doesn’t make as good a story as a Silicon Valley start-up with $50 million in venture capital funding, whose product is squarely aimed at the consumer.

Unfortunately, looking at the description of the camera benefits, it seems that Lytro has erred a bit too much on the consumer side. In order to appear more simple, they did not emphasize the full potential of the technology. Their three selling points “No fuss focus, Speed, Travel light” are aimed primarily at point-and-shooters. This could be based on market research concluding that the main user complaint about point and shoot cameras is shutter lag caused by autofocus. However, aren’t cell-phone cameras light, and simple enough ? They have huge Depth of Field (DoF) which makes precise focus a non-issue, particularly when the intended use of images (social sharing via low-res electronic use or 4×6 prints) doesn’t require high resolution. Moreover, point-and-shooters rarely want to post-process their pictures on the computer. They certainly didn’t want to mess with color balance and RAW files, so what is the chance they’ll enjoy dealing with light field files and setting focus ?

Lytro thinks that there will be a “magic” to be shared with

living pictures with which you can play, but while this is cool the first few times, it is so only superficially. I am not sure of lasting interest for a technology that requires a specialized plug-in or app, even if that app is built into social media sites so that you don’t have to install anything. And isn’t a video more “living” anyway ? Capturing life as a still image eventually is an artistic skill. Thinking that a technology, as advanced as it is, can provide a magic bullet for it will only lead to disappointment. Thinking that because of camera can “unleash” the light, you do need to understand and master all its variations will result in flat photographs, no matter what you do with with the light field, regardless of whether you focus the camera or not.

If you look carefully at the images provided in the Lytro demo, you’ll will notice that they have been selected to have a wide depth (kind of like the images that you see in 3D demos), with a foreground very close to the camera. Most of images that people take aren’t like that. Even the relatively large aperture of the Lytro camera would render those images as all in focus, therefore negating the effect. Because the Lytro camera captures the focal plane light field (instead of the full light field), it can create a synthetically generated narrower aperture, but not a wider one. Therefore, the Lytro camera will not allow you to get shallower DoF effects. There is already a free iOS App for that, SynthCam, written by no less than Prof. Marc Lavoy, who was one of Ng’s advisors.

Besides requiring a static subject, the main drawback of SynthCam is resolution – it is video-based. Although the Lytro camera has not yet been released, I guess that resolution could be a problem there too: the Lytro demo offers a zoom button, but when using it, you can notice that there isn’t much more additional detail. In Ng’s thesis, a medium-format camera was used. However, the microlens array of 292×292 effectively reduced the resolution to 0.1 MP (!) because each sampled vector direction needed an additional sensor section. It will be interesting to see what tricks Lytro has come up with to improve on those dismal numbers. Those micro lenses/prisms are not very efficient compared to camera arrays, wasting a lot of image data. By comparison, the Raytrix cameras offer a much efficient effective resolution of 1/4 of the original, at the cost of favoring a focusing distance, while the Lytro camera is focus-free. The dual aspect of resolution is high ISO sensitivity. If the pixels need to be made smaller to be able to sample enough directions, they will be more affected by noise. Will the loss be offset by the ability of the camera to shoot wide open ? So far Lytro has not announced any ISO numbers.

This could be a reason why the current offering is targeted at point and shooters. In the future, this may be less of a limitation. Higher resolution sensors are already possible, but manufacturers have backed from them because with current cameras there is little benefit. I am sure sensor manufacturers will be thrilled to have a new market that justifies absurdly-sounding higher MP counts.

To take a longer perspective, I do not think that the point and shoot market is the best prospect for light-field photography. This is advanced stuff, of interest to advanced shooters, aware of the nuts and bolts of photography, of shutter speeds and DoF, who appreciate that the shot is taken wide open, but the resulting images can have the DoF of a lens stopped way down. If/when the technology yields cameras with sufficient resolution for serious use at a competitive price point, I could see it embraced by professionals needing to capture a fast-paced moment which will not be repeated – sports photographers, photojournalists, wedding photographers, wildlife and underwater photographers. I could see it used by some landscape and close-ups photographers who want to maintain both a large DoF and fast shutter speed.

However, the greatest potential for light field photography will be realized by software tools that enable creative manipulation of the light field data. Once in the hands of artists, this will be a revolutionary technology.

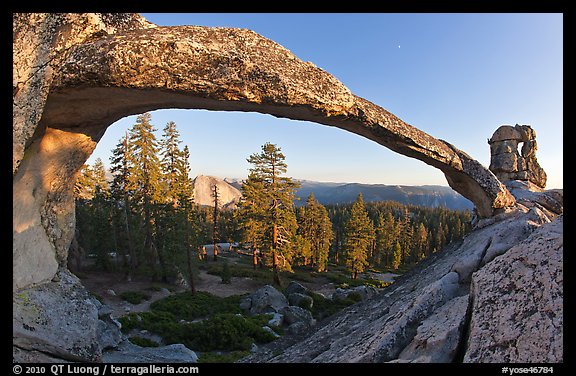

One obvious photographic application is creative use of blur, focus, and DoF in ways that were not possible before. View camera and tilt-(shift) lenses made it possible to focus on a plane not parallel to the focal plane to create images with either apparent extended DoF – or much narrower DoF than normal, leading to the “miniature world” effect. Light field images would let you exert total control over focus and blur wherever you want, with a “focus brush”. You wouldn’t be limited to a plane anymore. You could have several people at different distances, all sharp, and a blurred background. You could have a all parts of a close 3D object (such as a flower) all in focus, and a blurred background. It could start as a simple interface that let you click two points – like in the Canon DoF mode – and have everything in-between sharp. Eventually, your imagination would be the only limit.

Light field images, contain information from multiple viewpoints. While the full light filed would let you generate virtual perspectives from any viewpoint in the scene, the partial light field captured by the Lytro camera allows only for a slight perspective change. However, this is enough for changing perspective by moving a virtual camera in close-up photography, and producing 3D from a single lens capture. You could shoot from behind a chain link fence or a net, and remove the obstruction, by interpolating from the multiple viewpoints.

I think you’ll agree with me that this is more interesting than just a fast, light camera with no focusing fuss.

UPDATE Oct 24, 2011

Lytro unveiled the actual camera a few days ago. I still stand by the above, but let me add a few remarks:

1. The images are indeed low-resolution. I find it telling that the company totally declines to provide a resolution number, instead listing “11 MegaRays” (what is it ? nobody knows), as this is a number which would look OK if it was megapixels. In the interview with Robert Scobble, Ren Ng dodged twice the resolution question. He mentions “HD resolution” – which would be at most 1080×1080 since the image is square (some consider 720 to be HD, though) not 1080×1920, but then uses the term “rendered” which makes me wonder what the native resolution would be. Ren stated that resolution is not important, and I agree insofar as this product is positioned.

2. The camera is about as interesting for serious photographers as the sub-megapixel digital cameras of the 1990s. In fact, that demographic

likes their DSLR to be bigger and complex, and their skills to be noted, just the opposite of what the technology currently promises. There is not a single professional use I can think of – besides taking commissioned pictures to demonstrate the concept.

3. The camera is less practical (one more item to carry around, no large playback screen, no built-in cell/wifi communication for instant sharing) more expensive, and more limited than cell-phone cameras (no flash, video, cool photo apps), reducing its general public appeal.

4. The emphasis is on the “cool” effect and the “user experience” for everybody – or more precisely gadget lovers – rather than for photographers. Many tricks from the Apple playbook are used: the unconventional (and possibly ergonomically dubious) design which doesn’t look like any other camera, the minimalistic design, the reliance on company-hosted servers providing the controlled universe in which the “user experience” can be shared. In fact, at the moment the Windows version of the software is still in the works.

5. From a creative point of view, Lytro is betting on the “living picture” idea (presenting a web image that can be refocused by the user) rather on providing tools to control DOF. The effect is cool when first seen, but can it sustain a new esthetic ? Such an esthetic would invite users to deliberately seek images with much more depth and close objects than usual, and tell stories by letting the viewer discover picture elements by focusing. While I could see a few neat projects done by following this paradigm, the problem is that in great projects the idea comes first, and then the tool is chosen to match the idea, not the opposite.

6. This is a first generation product. It is positioned the way it is, because that’s the most exciting application of existing sensor technology. Excitement is what a start-up needs to generate. Regardless of how limited it may appear to be, it’s still remarkable that the first commercial iteration of a technology this innovative can be put into such a neat package and sold for such a reasonable price. Let see what happens when electronics will have progressed enough, for the camera to capture enough resolution.