Last winter, I traveled from March 12 to March 23 with my friend Regis Vincent to Alaska to seek the Aurora Borealis, also called Northern Lights. Since this was my first attempt, I sought to maximize chances of seeing the Aurora:

-

Auroral activity is strongest slightly above the Polar Circle, which in North America is most easily accessed from Fairbanks, served by an international airport.

-

Auroral activity follows a long-term cycle of about a dozen years, peaking in 2012-2013. Within the year, the peak usually takes place during the two equinoxes.

- March has generally much clearer weather than September in Alaska.

- While a bright moon provides illumination and color, it can potentially interfere with sky photography and overwhelm a faint aurora by lowering its contrast. Our stay coincided with the fourth moon phase (from half to new moon).

In order to remain mobile and keep an option to drive to wherever the weather is clear, I planned a road trip rather than a wilderness expedition.

This post is centered around my experience. Subsequent posts will detail logistical and technical aspects, which aren’t simple. At the end of this post, I also provide links to articles written by other photographers that give a great introduction to aurora photography.

Since I am a (adopted) Californian, the first night we decided to work not too far from Fairbanks as a “warm up”. If some cold weather equipment turned out to be inadequate, we could easily gear up. We initially planned to photograph at the Twelve Mile Summit (milepost 85.5 on the

Steese Highway), which offers a great view over snowy mountains, but it was just too windy to stay outside for any extended period of time, let alone attempt night photography. Snowplow operators recommended we go back promptly because the snowdrift threatened to block the road, which was closed a bit further, at Eagle Summit.

We drove down to a large pullout. As it was our first night in Alaska, we were excited to see the green band of light of the Aurora show up, but it was rather low on the horizon. My friend shivered during the night. As we drove back to Fairbanks, the aurora got brighter in the rear view mirror, putting on a much better show. We stopped many times to photograph, getting to a hotel only a few hours before dawn. Low (2).

We spent the morning shopping the numerous outdoor stores in Fairbanks, a better way to gear up, since they have polar-grade gear in abundance to try. I bought thick insulated, windproof bibs for less than $100, and my friend got a better sleeping bag. The next two days were to be at level 4 according to the

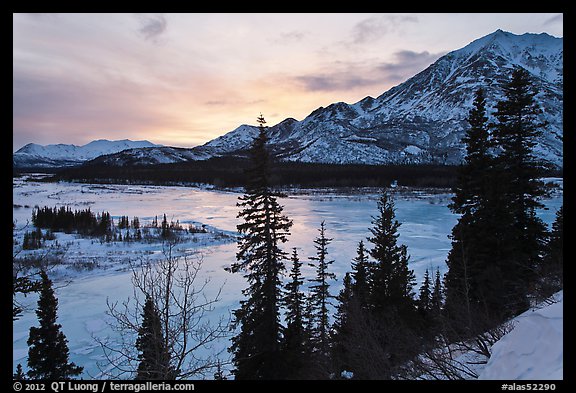

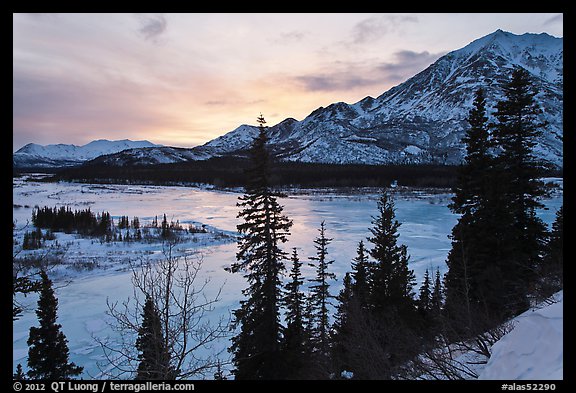

UAF Geophysical Institute Aurora Forecast. The higher activity levels give a chance to see the aurora far south of the Arctic Circle while with lower activity levels, the activity is confined around the Arctic Circle. To take advantage of the opportunity, we drove south on the Parks Highway, hoping to catch activity above Denali National Park. The afternoon was cloudy, with just a bit of color appearing at sunset.

As a landscape photographer, even in shots where most of the interest is in the sky, I look for significant land features to include.

Although our first night at the South Denali Viewpoint (milepost 135.2mi of Parks Highway), the aurora did show up, it was behind a dense cloud cover so we saw only a glow. Moderate (3). The next day, the clouds cleared up. At night, the aurora made a spectacular appearance above Denali and the Alaska Range, about forty miles away. Active (4).

Despite going to sleep (in the car, parked quite close to the highway since the pull-out was snowed-in) quite late, I got up to photograph the sunrise over the seldom-visible Mountain.

We drove back to Fairbanks, then went back to the Steese Highway. Since the next day we planned a long drive, we contented ourselves with observing the aurora from Cleary Summit. The scenery there consists mostly of meadows and rows of trees, but less than half an hour from Fairbanks, relatively high and free of light pollution, with a large parking area, the spot is popular with locals for aurora watching (larger version of the panoramic image). Active (4).

In order to get to the center of the aurora action, further north,

we tacked the famous Dalton, the northernmost highway in the US, and its most isolated (more on it in a future blog post). There is only one place for services, midway of 414 miles of road, at Coldfoot. After refueling there, we arrived in Wiseman at dusk. During the whole afternoon, the weather had been cloudy.

The weather forecast called for light snow at night, so we were actually looking forward to a night of sleep, but after cooking dinner, we noticed that the sky was clearing. While the mountains of the Alaska Range range were distant, here we were at the base of the Brooks Range mountains (northernmost in the world). As we looked for an interesting mountain as a foreground, we found prominent Mount Sukakpak (milepost 207 of Dalton Highway). Active (4).

North of Wiseman, the road was solid ice. From what I read, it’s actually nicer than in summer, when gravel flies. The Dalton Highway, built to support the Prudhoe Bay oil fields and Trans-Alaska pipeline, is traversed daily by more than a hundred 18 wheelers trucks, and only partly paved.

Although this year I didn’t set foot into Gates of the Arctic National Park proper, I managed to find a good view over the mountains that form the eastern boundary of the park. The Aurora was there again, for a sixth consecutive night. Active (4).

It had been a remarkably favorable week.

Resources

Here is a list of articles, all by photographers with great Alaskan aurora work, that I have found particularly useful:

Thanks for you help, and also special thanks to

Rolf Hicker, another photographer with great aurora images from Alaska and the Yukon.

For aurora forecasts, I’ve relied mostly on the

UAF Geophysical Institute Aurora Forecast which is easy to use and can even be accessed through dedicated

iOS App, Android App and mailing list. During the first few days of our trip, the server was down due to volume of requests, but the mailing list was working. Here are a number of other forecast sites:

Part 1 of 5: 1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

-32F temperature north of Atigun Pass on a sunny day

-32F temperature north of Atigun Pass on a sunny day

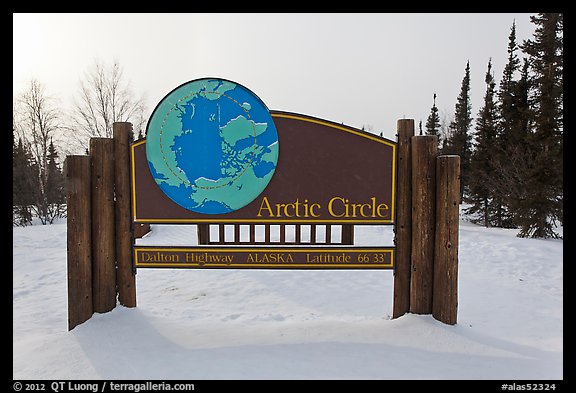

At mile 115, you cross the Arctic circle. This sign is found next to a pullout east of the highway.

At mile 115, you cross the Arctic circle. This sign is found next to a pullout east of the highway.