Part 3 of 3:

1 |

2 | 3

As part of my sea-to-summit visit of Hawaii Volcanoes National

Park, after

photographing the lava ocean entry and exploring around and above Kilauea,

I hiked to the top of Mauna Loa, the world’s largest volcano. In this

post, you will learn enough to plan your own trip there, or at least to know what you would see on this difficult, but exceptional and rewarding walk.

Why ?

Mauna Loa is the largest volcano in the world, spanning a maximum

width of 75 mi (120 km), and making up more than half of the surface

area of the island of Hawaii. If we consider its underwater

part of 16,400 ft (5,000 m) to the sea floor in addition to its

13,680 ft (4,170 m) height, Mauna Loa rises 30,085 ft (9,170 m)

from base to peak, more than the 29,029 ft (8,848 m)

elevation of Mount Everest from sea level, and twice its elevation

from base. The volume of Mauna Loa is approximately 10000 cubic miles,

more than 100 times the size of a Cascade volcano such as

Mt. St. Helens. Mauna Loa is an active volcano, which last erupted in

1984. Fumeroles can be seen in the summit caldera, most clearly at

sunrise and sunset.

Mauna Loa is not to be confused with the other large volcano on

Hawaii, Mauna Kea. Although Mauna Kea is slightly higher at 13,796 ft

(4,205 m), its summit, home to a large complex of astronomical

observatories, is easily accessible by a road and heavily visited. By contrast, you

need to hike to the Mauna Loa summit. No matter which route is

chosen, those are the most difficult trails in Hawaii. The quiet and

solitude are exceptional. You are almost sure to stand by yourself on the top. For the two days I was on the mountain,

I saw only one other party, and this was near the trailhead.

The hiking is an otherworldly journey. Hiking from the Mauna Loa

observatory, for the whole length of the

journey, I did not see a single plant, not even one of the

pionnering ferns. This is like watching the bare bones of the

earth. You could be on another planet. I expected the hike to be

monotonous because it is all lava, but I was surprised by the variety

of the lava landscape and the interesting variations in colors (reds, greens) and textures.

Mauna Loa looks unimpressive from a distance, because it is a

shield volcano. Hawaii lava flows are particularly fluid, which allow

them to travel farther than lava from more explosive volcanoes,

resulting in accumulation of broad sheets of lava, building up the

volcano in the form of a warrior’s shield with a slope of just 6%. However, the summit itself

turned out not to be a flat expense. I knew that it was made of a huge

caldera, but this didn’t prepare me for the experience of

standing at the very edge of vertical cliffs six hundred feet

tall, way above the spectacular caldera floor where ripples of hardened lava looked like

waves in an ocean.

Choosing the route

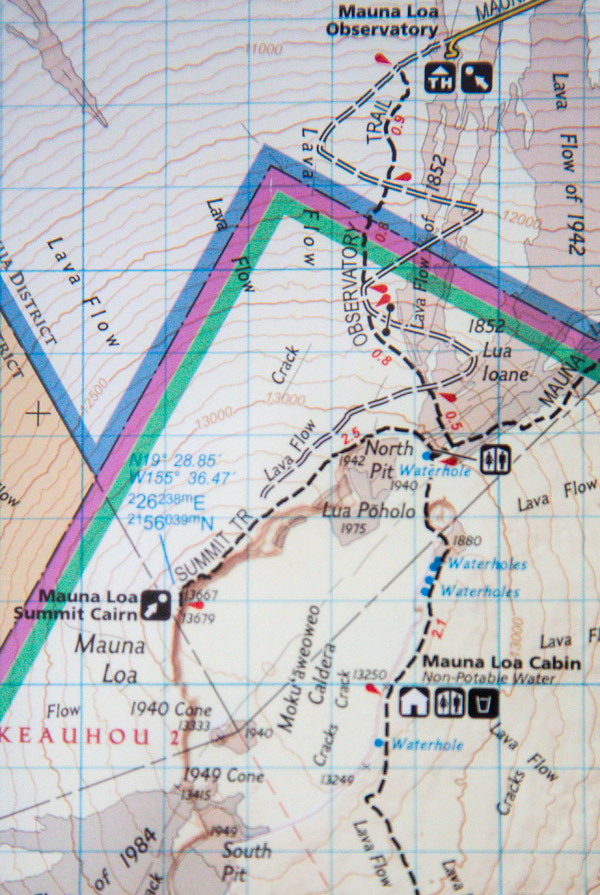

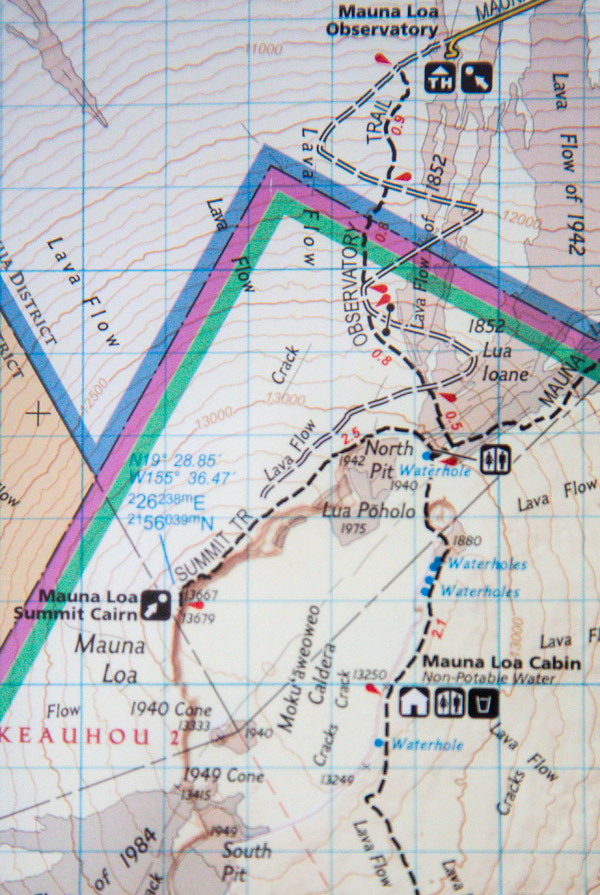

To reach the summit, there are a number of trails, of which only two

are traveled with any regularity, the Mauna Loa Trail,

and the Observatory Trail. Both trails meet at a four-way junction

situated near the North Pit (13019 ft), a secondary shallow caldera

at the northern edge of

the Mokuaweoweo summit caldera. The Mauna Loa Cabin (13250 ft) is situated on the East

side of the summit caldera, 2.1 miles from the North Pit. The summit (13,680 ft)

is situated on the opposite (West) side of the caldera, 2.5 miles from the North

Pit.

The most popular route, the Mauna Loa trail, starts at the Mauna Overlook at the end of Mauna Loa road

in Hawaii Volcanoes National park (6662 ft). The distance to the

North Pit is 17 miles, so total round trip distance to the

summit with a stay at the Mauna Loa Cabin is 44 miles, which take most

hikers 4 days to complete. Fortunately, you do not have to carry a shelter (although a

bivy bag can be useful in an emergency) nor all your water, since

there are two first-come, first-serve cabins on the trail with water catchment

reservoirs (boiling or filtration required), the Puu Ulaula Rest House (10035

ft) 7.5 miles from the trailhead, and the Mauna Loa Cabin previously mentioned.

The lesser-used Observatory trail starts at the Mauna Loa

Observatory (11040 ft). From there, it is 3.8 miles to the North

Pit. The round-trip distance to the summit is only 12.6

miles (add 4.2 miles if staying at the Mauna Loa Cabin) but the trail

is steeper and more rough. It is possible to do it as a day trip (not

a casual one !) but an overnight is preferable for most. Because of

the high starting point, you do not get a chance to acclimatize

progressively to altitude like on the Mauna Loa trail.

I very rarely get altitude sickness, yet when

sleeping at the Mauna Loa summit, I suffered a mild headache, despite

spending the previous nights at Kilauea (4000 ft), Mauna Loa overlook

(6660 ft), and the Mauna Loa Observatory (11040 ft) to which I had

driven the night before starting the hike. It might have been worse

– forcing me to descent prematurily – if I had not acclimatized before.

Because the Mauna Loa Cabin is situated opposite to the

Summit across the caldera, many hikers who stay at the Mauna Loa cabin

bypass the summit. Those who don’t get there at mid-day, since nobody really wants to hike the 4.6 miles from the Cabin to the Summit (count on 1 mile per hour at most) in the dark. I chose

instead to bypass the Cabin, so that I could photograph from the

Summit at sunrise, sunset, and during the night, although this would

mean having to carry a tent, sleeping pad, extra water, and camping in cold and exposed conditions instead of taking advantage of the comfort and protection offered by the Cabin.

The Mauna Loa trail is said to be the more scenic

of the two trails, however because of my limited time on the island, I

chose to hike the Observatory trail. For a group, a good alternative

would be to hike one-way using a shuttle. It takes about three hours

to drive from the Mauna Loa Overlook to the Mauna Loa

Observatory. Hawaii

Outdoor Guides 888-886-7060 can organize a shuttle service for

$100/person, with a minimum of $300.

Getting ready

The summit is situated above the usual inversion layer, which means

that it is often dry and sunny there, even though at lower elevations

(and in particular around Kilauea) it rains all day. I hiked down in clear

weather, but then drove the Observatory road in wet conditions with no visibility.

However, snow is possible at any time of the year.

Hiking with snow on the ground is very tricky, as the trail would

be very difficult to follow (likewise in bad weather) and the rocks slippery. During my previous visit to Hawaii, in May, a snowstorm prevented me from making the

trip to Mauna Loa. I settled for a

Mauna

Kea visit, determined to return another time to attempt Mauna Kea.

The base of Mauna Loa is in the tropics, but in February the summit felt more

like Alaska. I kept one of my water bottles inside my sleeping bag at night.

The one left outside froze overnight. Although temperatures can be

warmer in the summer, they still drop below freezing at night.

The temperatures are compounded by high winds. On the

second day, the wind howled all the way from the summit down

to the trailhead. Even though I was moving most of the time, I had to

wear my hat, fleece, top and bottom shell to stay warm.

I packed like I would for a winter mountaineering ascent.

I carried the same sleeping bag that I used to climb Mt McKinley, because that is the only winter sleeping bag that I own. For

my night on the summit, the -30F rated bag did not feel too

warm used inside a one-person tent. Since I expected to be camping on lava rock where stakes would not penetrate, I rigged the tent’s anchoring points with long loops of string.

In addition, I carried four quarts of water, since I didn’t go to the

cabin. There are no reliable water sources ouside of

the cabins, including at both trailheads. Since the air is so dry, drinking plenty, even in

cold temperatures, is necessary to avoid altitude sickness.

Sunscreen

and lipbalm are also needed at that elevation. I normally backpack wearing trail

running shoes, but for this hike, I wore lightweight hiking shoes

and was glad for the additional support and protection.

Because of the temperatures, hot meals and drinks are much appreciated. I found

cartridges for my ultralight butane/propane stove at the ACE hardware store in Volcano near the Park

entrance.

Overnight hiking requires a permit from the

backcountry office of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. This

improves your safety. The rangers provide

information about the weather, cabins and cisterns water levels, and

go through a checklist to make sure you are adequately

experienced and equiped. Here is the official

trail

information, some

contributed trip reports, and a most useful trail guide with

landmark mileages.

Hiking the Observatory Trail

The road to the Mauna Loa Observatory is unmarked. Driving on the

Saddle Road, I missed it at first.

It branches out not too far from the Mauna Kea road,

slightly East of it, at the base of a small volcanic cone. It took me 45 min to drive its 17 narrow and

twisting miles.

In the past it was marred by big potholes, but when I was there in Feb 2013, it had

been recently resurfaced, so my rental minivan was totally adequate.

The road ends at a gate – unlike for the Mauna Kea

observatories, and there are no facilities. Just

before the gate, there is an unpaved jeep road below, on the

right. Unless you have an expedition-grade 4WD high clearance vehicle, this is where you

park your car. After walking along that road for a third of a mile, you

see a trail sign on your left. The trail is much shorter than the road

because it cuts through switchbacks. I’ve read that driving

the rocky jeep road can take more time than hiking.

For approximately two miles, the trail consists just of rock piles

(cairns, locally called “Ahu”) marking an undistinct itinerary. I made

sure to spot the next one before leaving the cairn where I was.

On my way down from the summit, I found myself still on the trail, half a mile from

the trailhead, after dark. I didn’t get lost (I used a GPS to mark waypoints on my way up), but it took me an unusually long time to finish the trail, because it is extremely difficult to spot lava rock cairns at

night. Do not get caught on the trail after sunset unless you carry a

search-grade flashlight (500+ lumens). It would also be difficult to see those cairns in a

whiteout, which is why some recommend waiting them out instead of

trying to hike – and carrying survival gear to handle being stranded

overnight even if setting out for a day hike.

The trail sections on aa lava have been flattened and worn out, so they are clearly easier to hike than the

surrounding trail-less lava. When you are hiking on smoother pahoehoe lava,

you may have the impression that hiking outside the trail wouldn’t

make a difference. That would be a mistake, as you’d soon end up in rough aa lava flows, or get lost, as

there are no distinctive terrain features to orient yourself. In 1981,

a visitor who wandered off trail on Mauna Loa was never found despite a week

of the most extensive search in the Park’s history.

For another third of a mile, the trail joins the road – which

cannot not be driven past the National Park boundary, because of a

very solidly locked gate. At that point, I followed a

trail sign on the right, and for the next half mile, enjoyed

the only well-defined portion of the trail, as it follows green

olivine cinders bordered by a very dark lava flow. After crossing the jeep road a last time, and hiking

another half-mile, I reached the junction with the Mauna Loa Trail

(17 miles) , Summit Cabin trail (2.1 miles), and Mauna Loa Summit trail (2.5 miles).

Next to the junction, there is a shelter built out of lava

rock. Called Jaggar’s Pit – named after the volcanologist and founder

of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, Thomas Jaggar who spent many

nights there while watching eruptions – it is a mere hole in the

ground enhanced by rock walls and stairs descending into the pit. On the

second day of my hike, this was the only place where I was able to get

some respite from the wind after leaving the summit.

The junction is almost at the edge of the summit caldera, which would

be easy to access, as it is almost at the same level (13018 feet).

The summit was visible in the distance, but those

last 2.5 miles felt some of the longest I had ever hiked. I

understood why getting to the summit of Mauna Loa is so tough:

you are walking all the time on unstable lava rocks, at high altitude,

and unlike when hiking other, steeper mountains, you are staying at high altitude for an extended time.

When I reached the summit, marked by a huge cairn festooned with ritual

offerings, since this was uncertain from the beginning, I was delighted to find an excellent camping spot

surprisingly sheltered from the wind. Completing the 360 degrees

view, an older volcano emerged from a sea of clouds on the West.

At this elevation’s dry atmosphere, the sky shined with exceptional clarity thanks to the lack

of nearby light sources – the brightest of them being the glow of the

Halemaumau vent faintly visible in the distance. After dark, only a few yards from the tent, I set-up a 24mm f/1.4 lens on the Canon 5D mk2 for an all-night time-lapse sequence which captured the shadow projected by the quarter moon moving across the immense caldera, likely the first ever made in this place. I woke up one hour before sunrise to monitor the camera and update settings as night turned into day. The spectacle of the changing light and color at sunrise mesmerized me. I felt so privileged to be able to witness those moments from this spot.

Since I had brought only one tripod, I had to wait for the light to brighten before I could use my other camera, a Canon 5D mk3, to make hand-held landscape photographs in the other direction, making good use of the stabilized 24-105mm f/4 lens to create images that I’ve never seen done before at sunrise. The 600 feet of elevation gain from the junction meant that I was standing 600 feet right above the caldera floor, giving me an entirely different perspective than from the junction over this spectacular feature of Hawaii that only few get to see.

More images of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Part 3 of 3: 1 | 2 | 3