Photographing Fall foliage in Olympic National Park

Last October, I visited Olympic National Park to photograph autumn foliage. In this post, you will find out about the places where I found the best color, as well as my tips for photographing in the rain.

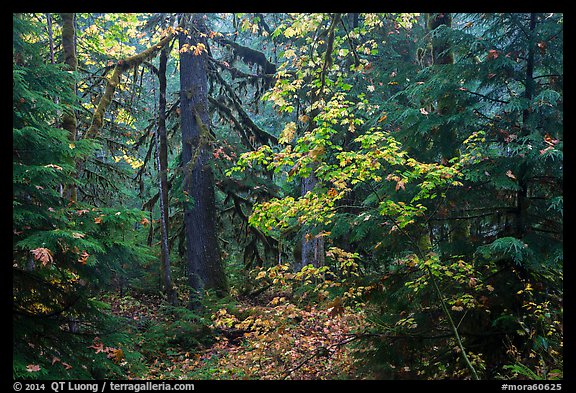

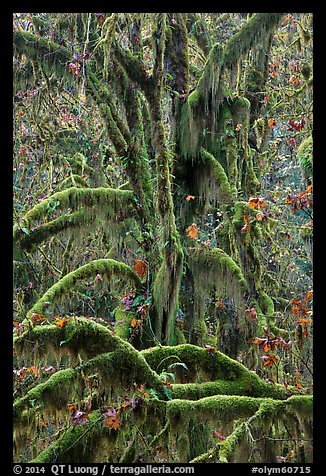

The Olympic Peninsula home to the lushest temperate rain forests in America. When you think about the rainforest, you think about a world painted all shades of green. However, the trees that support the iconic hanging mosses are mostly big leaf maples. Like all maples, those trees turn brilliant color in the autumn. Set amongst a sea of dark greens, the yellow leaves produce small, but striking color accents. The Eastern forests are so full of warm colors that sometimes you just see a wall of color. It is the contrast and interaction between colors that gives a color image interest. Sometimes, more interaction happens with fewer colors, which is the case in the rain forest in autumn.

Besides the big leaf maples, color in the Hoh Rainforest is also provided by vine maples. Unlike the big leaf maple, their smaller leaves tend to provide clusters of color, rather than the accents of the individualized leaves. Those two images are from the Hall of Mosses Trail (0.75 mile) which have both.

For most of the Pacific Northwest (Oregon and Washington) low elevation forests, and for the west side rainforests at Olympic, late October usually is the best time for fall color. However, I found most of the big leaf maples past peak on Oct 17-19 last year. I learned later that fall color started a bit early, but overall wasn’t great that year.

As implied by its name, along the Maple Glades Trail (0.5 mile) in Quinault, you will see plenty of majestic maple trees. The most colorful leaves were high up. Usually, cloudy conditions and soft light are much preferable to sunny days for photographing the rain forest. However, shooting up works better in sunny conditions with a blue sky than with a cloudy sky. I took advantage of a half-day weather break to create this image, unexpected for the Olympic rain forests in its perspective and color.

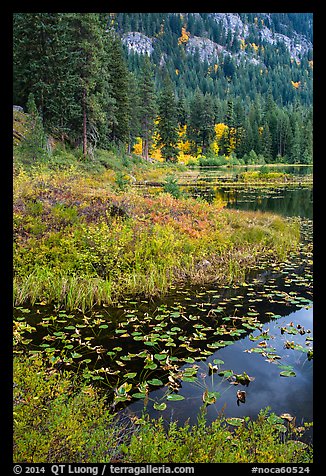

Although autumn color in the rain forests disappointed a bit, I found much more of it in the Sol Duc area of Olympic National Park. My favorite roadside spot was the bridge over the North Fork of the Sol Duc River. It’s the only bridge over the river on the road to Sol Duc, situated about 1/3 of the way in.

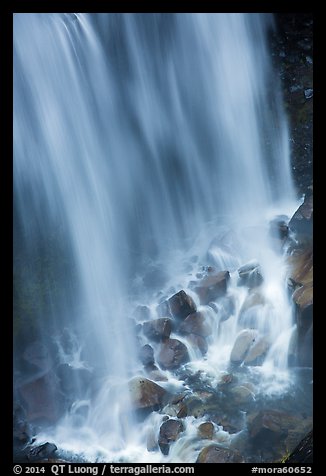

Sol Duc Falls (1.6 mile RT), is the most beautiful amongst the easily accessible waterfalls in the park, dropping 50 feet into a narrow gorge in a lush forest setting. The flow is good year-round. On the way, about 0.3 miles from the trailhead, I photographed a small stream, where in the spring water would cascade over mossy rocks. Late in the season, the stream had dried out, but the scene remained beautiful.

Although it was raining hard all day, I was able to keep myself and my camera backpack mostly dry by carrying an umbrella. I carried a rain cover for the camera, but did not use it, as it makes it difficult to change lenses. The forest I was hiking in cut all the wind, so the umbrella was sufficient to keep the camera dry. Since I always photographed on a tripod, I could operate the camera with one hand and hold the umbrella with the other hand with the proper ballhead friction settings. Whenever I needed to use both hands, I inserted the shaft of the umbrella into the collar opening of my rain jacket, letting the umbrella sit on my rain hat. Drops of water on the lens front element are inevitable and will show on the image as a fuzzy blob. To prevent them, I made sure to use a micro-fiber cloth to wipe out the front element of the lens before each shot. A small cloth quickly get saturated with water and becomes useless at drying a lens, so I carry a 10 inch by 10 inch cloth for rainy days.

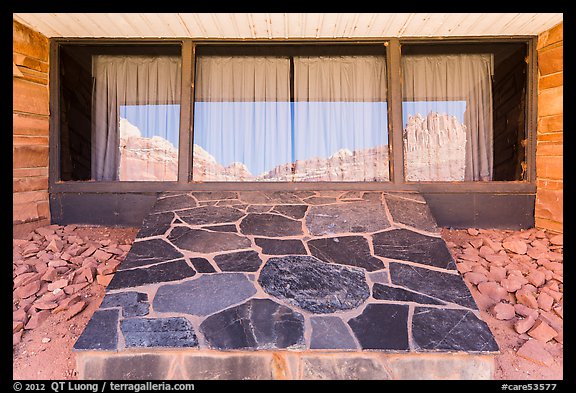

After photographing a whole day in the rain, my lenses had trapped a lot of moisture. It didn’t dry because I was sleeping in the car where the air was damp and cool. When I photographed at dawn in the forest (with a bit of light painting), this did not affect the image because it was still cold.

However, as the temperatures warmed up during the day, internal condensation started to cause fogging and blurring. Upon discovering the problem, I immediately returned to the car, cranked the heat, A/C, and ventilation to the maximum, and placed the lenses on the dashboard. After less than half an hour, the lenses were totally dried, and I hiked back for a re-take. In retrospect, I kind of like the eerie and impressionistic effect, and I am glad I did not delete the pictures! What do you think of it?