Landscape from the Bottom: Highlights of a Grand Canyon by Raft Photo Expedition

6 Comments

Anyone peering into the Grand Canyon for the first time is struck by two immediate, shocking facts: it comes without warning, and it is absolute. There is no soft transition, no gentle slope that prepares you. One moment you’re on the rim, the next you’re staring into an immense and unfathomable chasm—a vertical mile deep and layered with two billion years of Earth’s history. But as staggering as this view is, it is also detached. Monumental, yes, but distant.

To truly understand the canyon’s complexity, one must take a closer look—and that closer look is not available from the rim. From above, the Grand Canyon can feel overwhelming in scale but paradoxically simple in appearance: a vast, continuous chasm with layered rock receding into hazy distance. But that view flattens its richness. The real Grand Canyon isn’t a single space—it’s a world composed of thousands of distinct micro-landscapes, each shaped by variations in rock type, erosion, water flow, elevation, and exposure to sun and wind.

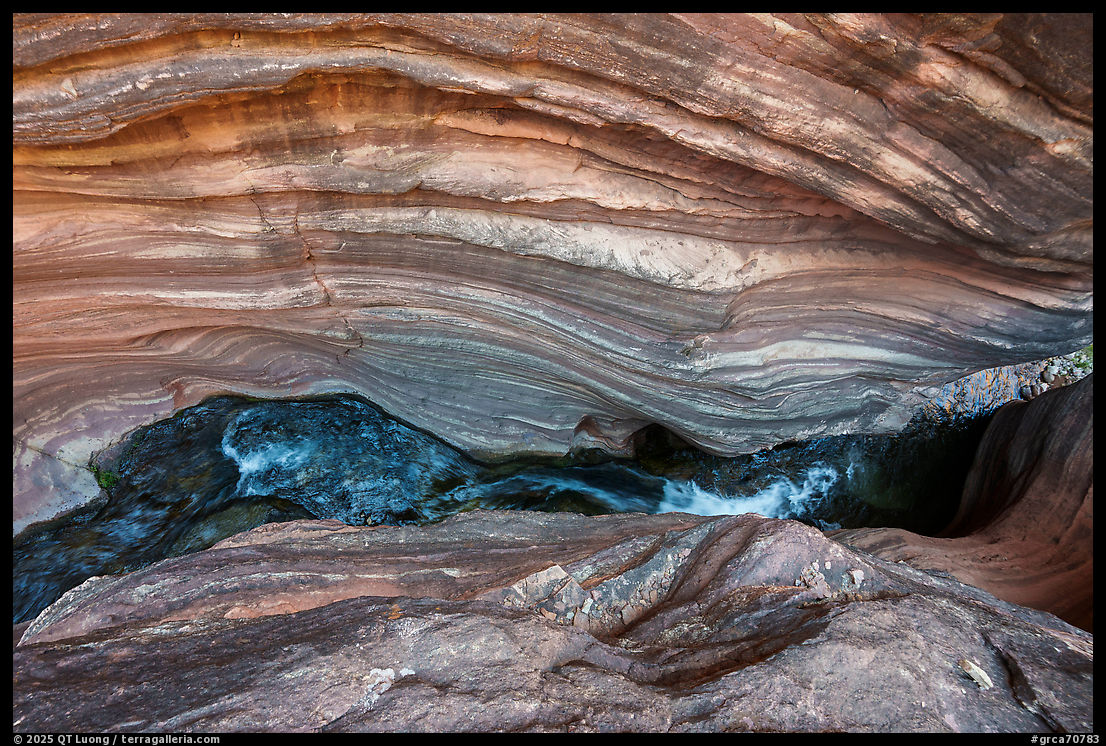

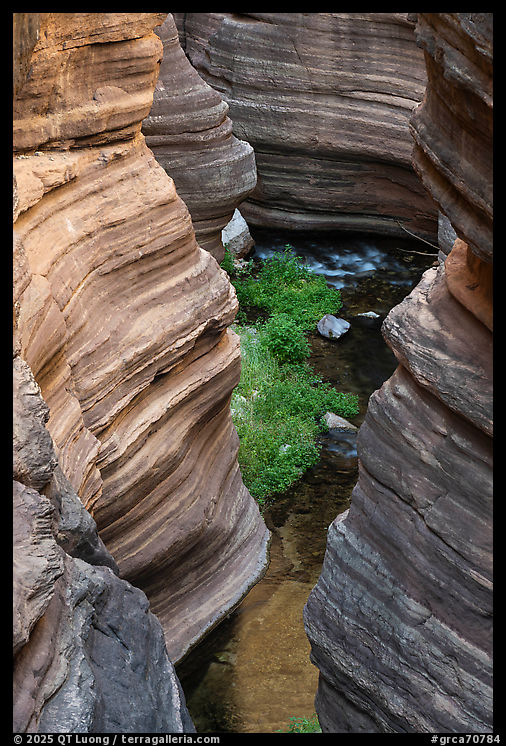

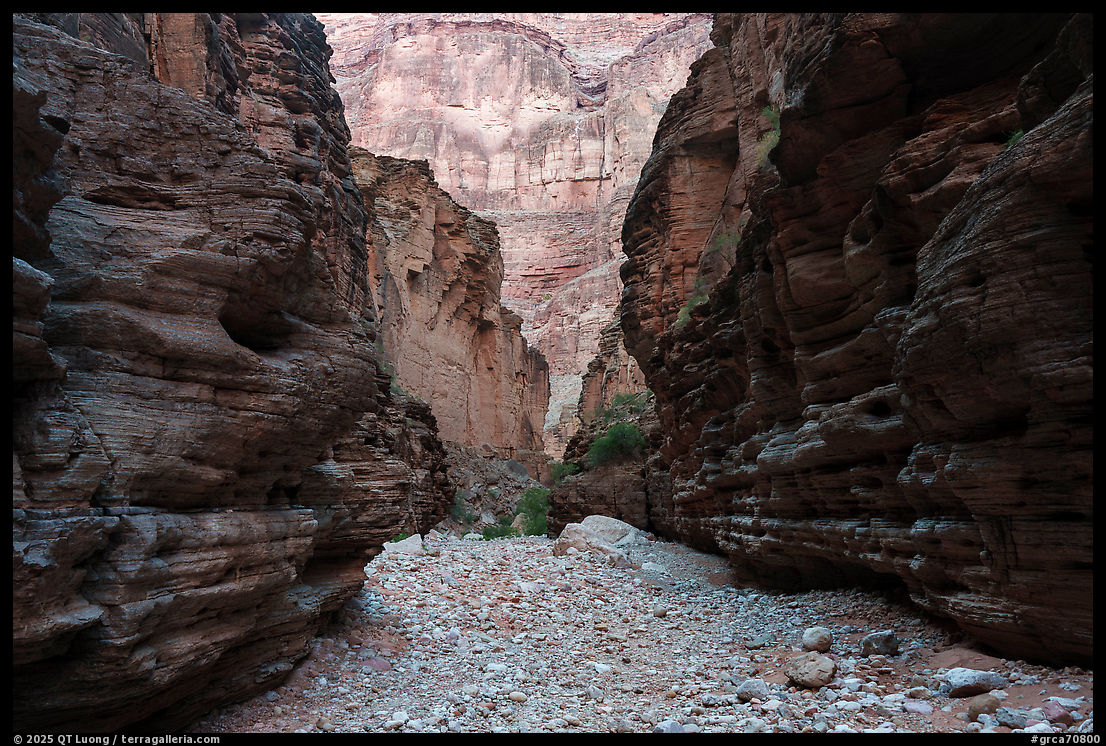

There are alcoves where hanging gardens flourish in perpetual shade, and just around the bend, scorched terraces where nothing survives. Slickrock domes rise beside narrows barely wider than your shoulders. Ancient lava flows cross horizontal sedimentary layers, and entire amphitheaters are carved into soft shale and limestone. Rock that appears static from afar turns out to shimmer with embedded fossils, mineral streaks, or desert varnish when seen up close. Even the soundscape shifts constantly—from deafening rapids to dry, echoing silence.

Photographically, this means that the Grand Canyon is not one landscape but a multitude—revealed slowly, intimately, and often unexpectedly. The complexity isn’t just geological; it’s sensory, ecological, and spatial. To engage with it requires movement through it, time within it, and the flexibility to respond to what the canyon offers moment by moment. That’s why being at river level, day after day, changes your relationship to the place. You stop seeing “the canyon” and start seeing canyons, alive, and endlessly varied.

Sure, it’s possible to backpack into the canyon, and doing so offers an unmatched sense of immersion – and effort. But it can also be grueling, especially if you bring serious photography equipment. When I hiked from the North Rim to Deer Creek (a waterfall minutes away from where our raft beached) via Thunder River with my view camera in the early 2000s, such was the amount of water to be carried that despite not packing a tent – exposing myself to a bothersome rodent on the last night of my outing – I started with a seventy pound backpack. On my way out, I climbed over five thousand feet. Even if you have the stamina and skill, your access remains limited. Trails are few, and they constrain your movements to established routes.

A river trip offers something radically different: easy access. From the river, you are no longer confined to the rim’s distant view or the narrow confines of a corridor trail – as are called the main trails, the Bright Angel, South Kaibab, and North Kaibab Trails, which together account for over 75% of all trail usage in the park. You travel through the heart of the canyon, often along sections unreachable by foot. Sculpted narrows, lush hanging gardens, ephemeral waterfalls, ancient rock art panels, and side canyons hidden from above—these are features only the river unlocks.

For our journey, we traveled by motorized raft. While this meant giving up some of the quiet solitude, sense of adventure, and intimacy of oar-powered travel, it offered a major advantage: speed. In spring, the Colorado River flows at about four miles per hour. A motor rig also reaches four miles per hour, resulting a speed of eight miles per hour. In contrast, an oar trip travels at half that speed, meaning more time in transit. With the motor, we reached each day’s destinations faster, giving us significantly more time on land, where the richest photographic opportunities awaited.

There are certainly compelling images to be made from the raft, and I’ll explore those in the next installment. But there are inherent limitations: you can’t stop for long, the boat is always in motion, and shifting your viewpoint is limited. On land, you reclaim control. You can take your time, explore angles deliberately, get close to your subject, work with a tripod, and use slow shutter speeds. Some serious photographers barely shoot while floating. They wait for the landings.

In some sense, every stop holds potential. At one location chosen for lunch simply because the cliffs offered shade, two of us wandered a short distance and discovered a hidden pocket of white sand tucked beneath a deep overhang of red sandstone. While the rest of the group ate and rested, we happily photographed in that quiet space. Moments like that are a reminder that in the Grand Canyon, beauty isn’t limited to the named landmarks. But even considering only the well-known sites, there are far more photographic opportunities than a single trip can accommodate. That’s especially true if you’re trying to optimize your time around the quality of light, as we were on this photo-centric expedition. Coordinating to be at certain locations at specific times was one of the more challenging aspects of the trip and required close collaboration with our river guides. Take, for example, the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers, where we wanted to be at sunrise. Camping is prohibited for miles upstream of the confluence, so the only way to photograph it at sunrise is to camp directly across the river. To secure that rare campsite, we arrived by midday the day before. The next morning, we ferried across at first light—leaving camp set up—and returned for breakfast after the shoot. That return trip, against the current would have been impossible without a motorized raft.

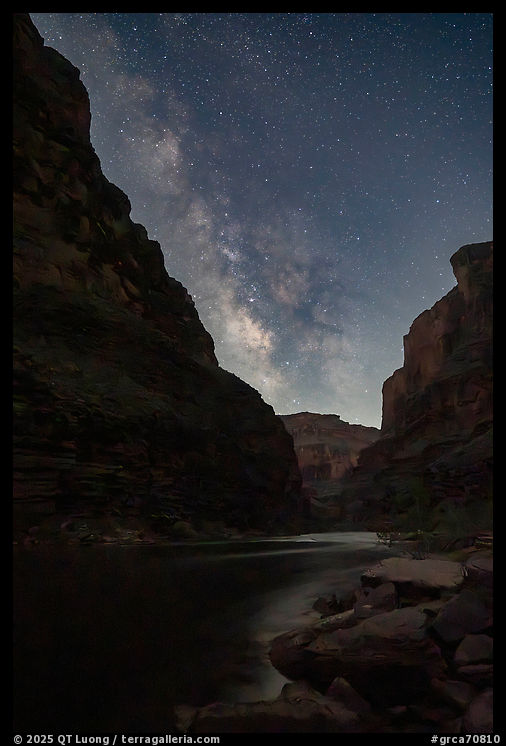

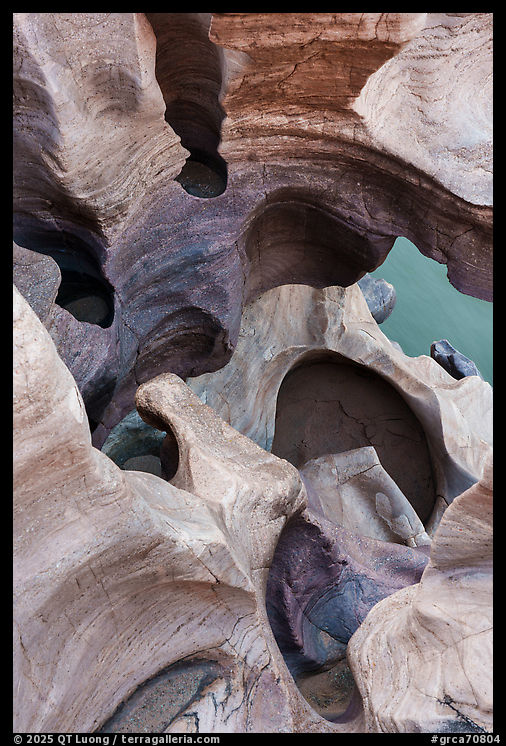

The images below are presented in chronological order, following the journey as it unfolded. Some of the highlights include North Canyon with distinctive swirling textures in the rock and sculpted pour-off – I was surprised to see an opaque green pool at its base where on my previous trip a clear reflection pool stood; the vast alcove of Redwall Cavern, estimated by John Wesley Powell to hold 50,000 people; the turquoise waters and travertine terraces of the Little Colorado River as well as the mixing of waters at its confluence with the Colorado River; Shinumo Creek, with its waterfall nestled in a sculpted canyon; Elves Chasm, a lush oasis where a waterfall plunges into an emerald pool beneath hanging gardens; Blacktail Canyon, a narrow slot cut deep into ancient Vishnu Schist that reveals some of the oldest exposed rock on Earth; Deer Creek, where a powerful ribbon of water tumbles from a hidden gorge; Havasu Canyon, a paradise of turquoise streams winding through sheer limestone cliffs; National Canyon, known for its layered narrows and stark transitions between rock types; and Pumpkin Spring, a vividly colored mound of mineral deposits that oozes warm, sulfur-rich water directly into the Colorado River near water-sculpted potholes carved in a surreal swirl of rocks. Besides those known highlights, the campsites themselves revealed unexpected photographic opportunities, both by day and night—sometimes a few steps from the river’s edge, other times reached by climbing to little-used vantage points. In approaching these images, I sought to move beyond familiar views, focusing instead on the canyon’s layered textures, shifting light, and the sensory variations that emerge through movement and time. Rather than depicting the Grand Canyon as a single, fixed landscape, these images aim to evoke the complexity of place as it is experienced from within—a space of constant transformation, where immersion reveals what distance cannot.

I love your photography and have your books on the national parks. I have only seen the Grand Canyon from the rim however, I saw it on three consecutive days during the fall. It looked completely different each time as the sun, fog and clouds would mingle in the huge chasms.

I’m concerned about what problems you encountered at Carlsbad Caverns. I’m imagining they would not allow a tripod which is sad. But please tell me. I have been to the caverns only once and found them enchanting. I use smaller format cameras and tried longer exposures by resting my camera and body on metal pipes, handrails and concrete blocks. This only gave me slower shutter speeds not true time exposures.

Thanks for your continuing work and newsletter

Sincerely

Jim Denman

Thank you, Jim, for your concern. I was going to reply in full here, but I think the extent of my “problems” at Carlsbad Caverns and one solution I used rather successfully warrant a separate post, which will be coming out this month.

These photos are absolutely spectacular. Really beautiful. Did yuh travel by motor raft with an organized company that offers these trips? If so could yuh share the name of the outfitter? Many thanks!!

Thank you Susan. Yes, as mentioned in the previous post, we used an outfitter (their website) because it is extremely challenging to do otherwise. But ours was a charter adventure specifically geared towards photography. See my answer to Martin Cutrone on that previous post.

This looks and sounded like a great adventure! Love you images! The trip sounds like it was designed for photographers. The advantages of using a motorized raft was interesting. Can you give me some details about the trip origination?

Hi Alan, you care absolutely correct that the trip was designed for photographers. The trip was announced here in March 2024. What details would you like to know?