The Trek – Zanskar, 1989

3 Comments

https://www.terragalleria.com/blog/the-trek-zanskar-1989

In the summer of 1989, I set foot in Asia for the first time—a formative journey that expanded both my view of the world and the role photography could play in it. A few years earlier, college friends at Polytechnique had introduced me to climbing, and I had taken to it immediately. Photography followed naturally: a way to share the beauty and scale of the high peaks with those who couldn’t be there. Before that, my only venture beyond Europe was a brief stint at a military skydiving camp in Morocco—memorable, but worlds apart from what lay ahead.

In the winter of 1987, beginning what would become a productive decade of ice climbing, I enrolled in a course offered by Godefroy Perroux, a pioneer and central figure in French waterfall ice climbing. Relaxed and generous, Godefroy had a wide circle in the climbing community. One of his friends, Richard, came along to assist. Among the attendees was Chantal Mauduit, who would soon make her mark in the mountains. We all stayed at Godefroy’s cozy cabin near the Alpe d’Huez ski resort. The time we spent together led to friendships, and eventually Richard invited Chantal and me to join him for a Himalayan trek.

Click to enlarge

As a young mountaineer, I dreamed of climbing in the Himalayas. But for my first visit, I thought it wiser to begin with a trek rather than attempt a summit. Part of the Himalayas – including Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world – are in India. Richard proposed we cross the Himalayan range from north to south via Shingo La, one of the range’s more accessible passes—free of steep slopes or glaciers, yet still above 5,000 meters (16,000 ft). From the pass, we’d attempt a nearby undocumented 6,000-meter peak. Though modest compared to Himalayan giants, it stood over 1,000 meters higher than Mont Blanc, the highest summit in Western Europe.

Our trek would take place in Zanskar, a remote high-altitude valley on the eastern side of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, now part of Ladakh. Home to about 10,000 people and isolated by mountain barriers, Zanskar had seen little outside contact. Ladakh had been closed to foreigners until 1974 due to regional border tensions with Pakistan and China. Even as tourism to Ladakh increased through the 1980s, it was mostly to Leh and the wide Indus River Valley. Zanskar remained far off the main circuit, inaccessible to all but the most determined travelers. In the first years after reopening, the area saw only a few hundred tourists pass through its capital, Padum. If Zanskar was known in France at all, it was largely thanks to the work of photographer Olivier Föllmi, reportedly the first Westerner to walk the frozen Zanskar River, resulting in his book “The Frozen River” (1990). One of the coldest inhabited areas on Earth, Zanskar is cut off by snow for eight months of the year. But from mid-January to early February, the frozen Zanskar River forms a perilous hundred-mile ice route between Leh and Padum.

Click to enlarge

Just reaching the starting point of the trek became one of the most intense experiences of my first 24 years. When I stepped off the plane in New Delhi, groggy with my first experience of jet lag, I was plunged into a world unlike any I had known—a dense, a dense chaos that marked my first encounter with a developing country. Richard planned two consecutive treks—one with Chantal, and one with me—so I had a few days on my own before we met. The conditions at the cheap hostel where I stayed were a shock, but it was on the street that I felt most overwhelmed and bewildered: the chaos, colors, tuk-tuk and crowd noises, smells, heat, sacred cows in the traffic, and the open, confronting poverty. Still, I felt temporarily good when I summoned the will to try street food—abundant vegetarian fare that turned out to be both new and delicious. As if that weren’t enough stimulation, I took a day trip to Agra to see the Taj Mahal, riding a rickety local tour bus while Bollywood videos blasted on the overhead screen, competing with the roar of the wind through open windows.

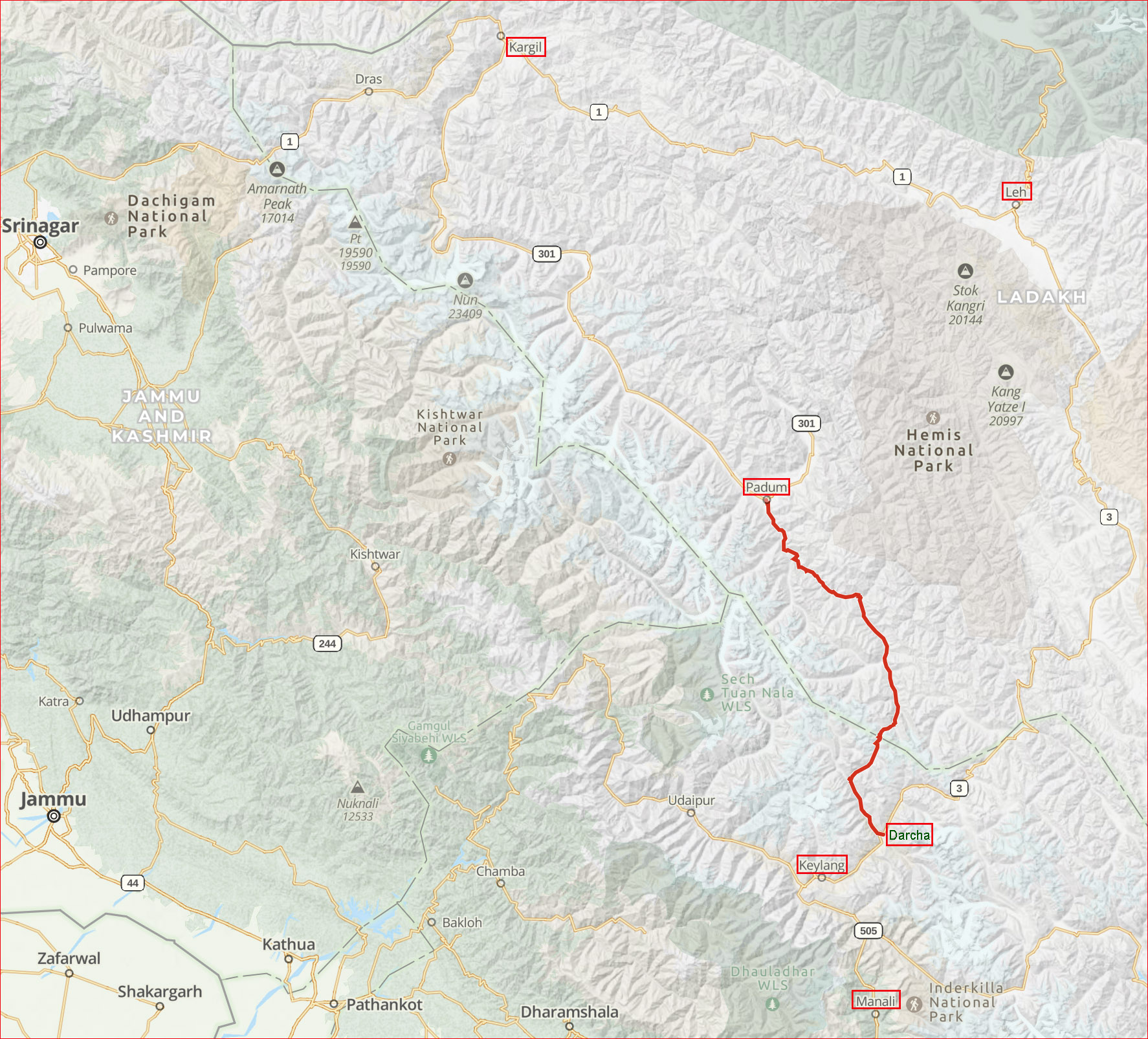

After managing to locate the Indian Airlines office and purchase a one-way ticket to Leh, I finally reunited with Richard. From there, we boarded a large truck bound for Padum, Zanskar’s main town, lay 62 miles from Leh as the crow flies. Though 276 miles away by e roads 1 and 301, the journey took three days. Narrow, rough, winding, and subject to landslides, the road from Kargil to Padum had been built in 1978 and was navigable only by the sturdiest vehicles. Our truck carried a dozen passengers in its open bed, without seats or roof. On the unpaved road, we were quickly caked in dust. I began to suffer from diarrhea—likely from eating fruit sold by street vendors in Delhi—and Richard scolded me for my ignorance of precautions to be taken in developing countries. He mentioned that Chantal had been similarly sick and had resorted to a steady diet of pills. With no practical way to stop for toilet breaks, I stopped eating altogether until we arrived in Padum. Between the illness, the rough transport, my fasting, and the high elevation of 3,600 meters (12,000 feet), I arrived barely able to walk.

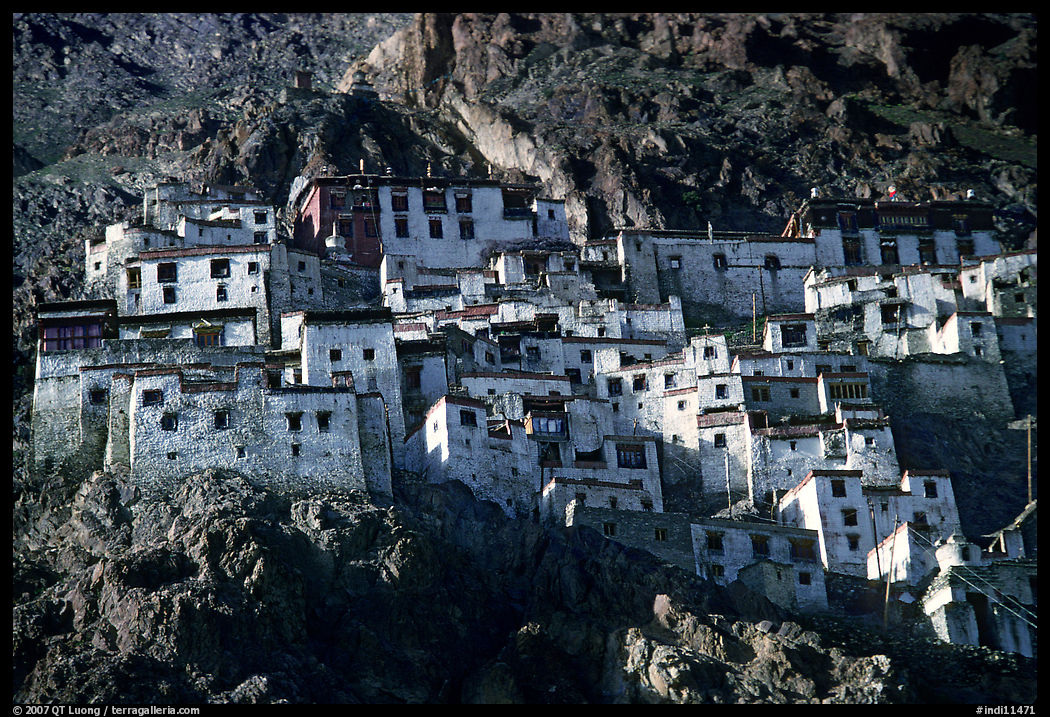

Padum was the southermost point of the road. All travel beyond had to be on foot. Richard left for a solo week-long trek while I recovered in a basic guesthouse there, making endless visits to a hole-in-the-ground toilet – very sustainable as it doesn’t waste precious water and generates compost. After a few days, I had regained enough strength for a short excursion to the Sani monastery (where a bite from a feral dog gave me days of anxiety), followed by a four-day round-trip trek to Phuktal Gompa (monastery). That remote sanctuary, a honeycomb of fortress-like structures clinging to the mouth of a giant cave above a gorge, resonating with the sound of bells, horns, and chants, remains one of the most spectacular and affecting places I ever stayed.

Ladakh, once a Himalayan kingdom, shares more geography and culture with Tibet than with the rest of India. Hearing the Dalai Lama state during his (current) 2025 visit that Tibetan Buddhist culture is better preserved in Ladakh than in Tibet itself – where it has been eroded by Chinese coercion – reminded me just how intact that world still felt when I walked through it decades earlier. More than 90% of the population practices Tibetan Buddhism. As a child, my parents regularly took me to a Vietnamese Buddhist temple in the outskirts of Paris, across the valley from the Polytechnique campus. I still remember the gentle scent of incense, the delicate lotus motifs, and the serene statues. In Ladakh, by contrast, the gompas felt darker and more elemental. Murals of fierce deities with bulging eyes, spinning prayer wheels, and the dim glow of butter lamps created an atmosphere at once visceral and mysterious. Every village has its monastery with hauntingly vivid, centuries-old artwork, and trails are lined with chortens — Buddhist shrines that I learned to pass clockwise, in respect. I memorized a few mantras, especially essential in Tibetan Buddhism, to help pace my steps. They reinforced the meditative and sometimes monotonous nature of walking all day long through such austere landscapes. Ladakh is a high-altitude semi-desert in the rain shadow north of the Himalayas. Outside the irrigated barley and lentil fields near villages, little greenery grows. Encounters on the trail were rare, and none of them included foreigners. Conversation was limited to signs and gestures, but the warmth I felt from the villagers transcended language. That people living in such difficult conditions could radiate such calm contentment seemed to speak to the spiritual depth of their beliefs. Realizing that this pre-industrial culture, although so different from mine, had an equal validity, I developed great respect for it and tried to learn as much as I could.

Looking back now, I see that this early exposure to another way of life—where material means were few, but meaning was abundant—planted the seeds for the themes that would guide my work later. Landscapes are not empty stages but interwoven with the lives, beliefs, and survival strategies of those who dwell in them. Resilience and reverence can coexist in places where life is carved from scarcity. To inhabit a landscape is to enter into a compact with it—one that modern development often breaks unilaterally.

After Richard and I explored the open valley surrounding Padum, we began the 90-mile trek to Darcha, a town south of the main Himalayan crest. The route followed the valleys of the Tsarap and Kurgiak Chu rivers. It wasn’t a recreational trail but the only connection between scattered villages, with foot and horse the only means of transportation. In the early stages, we slept and ate in those villages. Services were minimal, as inhabitants lived in near-complete self-sufficiency based on farming and cattle-rearing. A few locals offered us a place to sleep—bare rooms with dirt floors—and simple meals of roti (flatbread) and dal (lentils), often with tea flavored with yak butter of indeterminate age. In this zero-waste society, yaks are rarely eaten; they are too essential for farming, milk, transport, fur, and even dung, the main source of fuel in this treeless region.

Because we carried a rope, crampons, ice axes, and other mountaineering gear for our summit attempt, we hired a porter who also ferried extra food and camp necessities—essential as we ascended into higher terrain with no permanent habitation. We each hiked at our own pace and typically met up at the night’s camp. Only later did I realize that what we were doing wasn’t backpacking in remote terrain—it was trekking in the truest sense: relying on local knowledge and hospitality, moving through a living cultural landscape rather than immersing in self-contained solitude.

Since the Himalaya Range acts as a barrier shielding Ladakh from most of the monsoon, the weather had been mostly warm and dry until we reached the Shingo-La (pass). As clouds gathered, we pushed upward on snowy ridges to about 5,800 meters (19,000 ft) according to Richard’s altimeter, but with no weather forecast and rising uncertainty, we decided to abandon the summit attempt. Descending into Himachal Pradesh, we were struck by how the landscape changed. On the southern side of the Himalayas, the green valleys of Lahaul replaced the dry mineral terrain of Ladakh. Eventually we reached Darcha, where the road resumed. From there, it was a bumpy but mercifully seated ride to Keylong. We spent a few days exploring the area, including the Kunzum La (pass) connecting Lahaul from the Spiti Valley. After misjudging a side ascent, I was caught by nightfall and sheltered with a welcoming sheep herder who opened his encampment to me without words. Afterward, we continued to Manali where we parted ways, with me taking the bus for another long day to New Delhi.

The journey remains one of my most formative experiences. Though set in the mountains, it pushed me far beyond my comfort zone and into contact with a way of life entirely different from my own. Until then, most of my photography had focused on mountaineering in the Alps. This was my first real cultural immersion—and the moment my interest toward human geography and place-based storytelling began. I went to Zanskar chasing altitude, but what stayed with me were not the peaks—it was the quiet durability of life in their shadow. I didn’t realize it at the time, but that encounter altered my sense of what photography could do: not just depict grandeur, but bear witness to the fragile balance between place, people, and time.

During an entire month in India, I had exposed only ten rolls of film. I hadn’t yet learned that film is cheap compared to travel. I was dismayed that due to a loading mistake, the first one, which included the Taj Mahal, was blank – two decades would pass before I would return with a much different camera. At the time, I shot Kodachrome, a slide film reputed for color but unforgiving of exposure errors. Since I didn’t bring a tripod, low-light photography, including all interiors, was not possible. My knowledge of photography was still lacking, and most of the photographs from this trip were technically or compositionally flawed. But unlike early digital media, the physical slides remain fully readable, and their color barely faded. Their slightly aged palette proved surprisingly apt at restoring memories to a vivid status. The place names and dates that I had written on the slide pages formed an accurate record.

Those slides, imperfect as they are, belong to a lineage of exploration photography that once sought to make remote places visible to others. But the ethic of that practice has evolved. Today, I no longer see photography as an act of “revealing the untouched,” but rather as a way of witnessing change—and asking what is at stake in that change, especially for those who live closest to the land.

While retracing the trip for this write-up, I turned to online maps, and was shocked to discover that the once-remote and rough trail from Padum to Darcha that we trekked is now a paved two-lane road. Although some parts had been completed earlier, the final stretch over Shingo La only opened last summer. A tunnel under the pass is under construction to make the route passable year-round. Further north, the traditional frozen Zanskar River route is now also a paved road, completing what is now known as the Zanskar Highway. I am grateful I undertook the journey when it still was remote, raw, and difficult. My images—though imperfect—have become not just personal memories but historical traces, glimpses of a world before modern infrastructure reached it.

In 1989, the region still saw very few outsiders. I met no other foreigner during my four-day walk to Phuktal and encountered only a handful in Padum itself. Zanskar still felt utterly remote— not just geographically, but culturally. The journey felt as much an act of endurance as of curiosity, far removed from today’s fly-in trekking culture and convenience tourism. Since then, the number of visitors has increased by a factor of twenty. Mass tourism introduces outside values that risk unraveling traditional ways of life, inviting young people to equate Western lifestyles with progress—even when those models conflict with local needs and ecological wisdom. Few reap the greatest benefits, while the heavy social and environmental costs are borne by many. The opening of roads brings opportunity—but also loss. This tension mirrors what I’ve since encountered closer to home. My early experience in Zanskar showed me how landscape and culture are inseparable. That insight continues to guide me.

Wise words flow to these exquisite photographs. Thank you.

Om Mani Padme Hung _()_

Thank you for this wonderful story. What an amazing journey you shared, both physically and of your mind.

Thanks Colleen and Elizabeth for your kind words!