Photo Spot 57: National Park of American Samoa – Siu Point, Ta’u Island

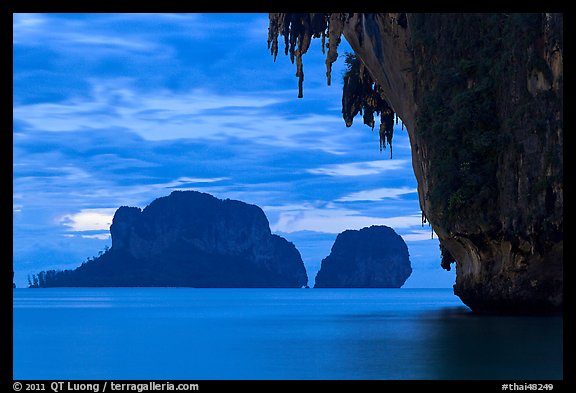

The distance to the continental US is certainly the reason the National Park of American Samoa is the second least visited of the 58 US National Parks. To get there took me ten hours of flight from California, plus a stop over mid-way in Hawaii. If it was closer, I’d expect that park to be a popular unit. It is one of the most beautiful parks, graced with magnificent sand beaches and pristine coral reefs, bordered by tropical rain forest islands ringed with impressive cliffs.

The park comprises sections of three islands, Tutuila, Ta’u, and Ofu. The later two are part of the group of Manu’a islands, a half-hour flight from Tuituila, the main island. Since it was such a long trip to get there, I made sure to visit all three of them. The least visited island on that most remote park is Ta’u Island, where the Park doesn’t have any facility. As camping is not allowed and no commercial lodgings were available, I made arrangements for a home stay with a Samoan family with some help from the NPS office in Tuituila.

As I disembarked from the small prop plane and walked to the tiny office, my host had no problem finding me: I was the only visitor. I loaded my gear on the back of his pick-up truck amongst a jumble of pandanus leaves and coconut hulls. We drove on through a beautiful coastal road which was totally empty, and arrived at Fiti’uta, a village consisting of maybe a dozen houses and the traditional communal Fale.

The Samoan culture is Polynesia’s oldest. The first people on the Samoan islands came by sea from southeast Asia some 3,000 years ago. However, Samoans believe their God Tagaloa created the first man and woman on Ta’u and that all people descended from them. Ta’u is also the site of Margaret Mead’s landmark study for Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) which was for forty years the most widely read book in the field of anthropology. My host’s wife had prepared a great looking dinner, but since I am a vegetarian, I had to content myself with taro roots. The next morning, my host drove me past Sau’a, that mythical site of the creation of humanity according to Samoan beliefs. He dropped me at the end of the dirt road, named Siu Point. I would not see another person there.

The coast was the wildest I had ever seen. After my first glimpse of it, I tried to hike along the shore in order to get closer to the sea cliffs that I saw in the distance, which I read were the tallest in the world. However, I was making slow progress, as I had to hop from boulder to boulder with my heavy backpack. The black, volcanic boulders were quite sharp. Seeing that the perspective did not change significantly, I turned back in order not to be late for the evening pick-up.

I had initially planned to stay only two days on Ta’u before flying to Ofu, but my host told me that the flight for the next day had been canceled due to an incoming storm. Since there was only a flight every two days, this meant two more days on the island. At the time of my visit, information about Ta’u was scarce, and I was aware of the trails to Laufuti Falls or Lata Mountain. My understanding was that the other parts of the National Park on Ta’u consisted of a roadless jungle inaccessible without a guide with whom I would have needed to make arrangements with in advance. Therefore, all my host could do for me was to drop me off again at Siu Point. Past the disappointment of having to shorten my stay on Ofu, and revisiting the same spot, the prospect of a tropical storm was actually quite exciting, so I prepared myself for a wet day, since there is no shelter there, and I would be on my own for the day.

Fortunately, it poured only for brief moments, that I waited by sitting under my umbrella. The rain actually proved a welcome respite from the tropical heat. In the end, it is as if the Polynesian gods chose to reward my perseverance by rainbows, a show of big crashing waves under a dark sky, and then dramatic light at sunset. Just as the dark clouds were starting to yield an intense shower, I saw the headlights of my host’s truck. On the way back, as it rained so hard that it was difficult to see the road through the glare of the lights, I could see his surprise when I told him that I had a great day.

See more images of American Samoa

See more images of Siu Point

I had first noticed Michael Frye (see his photographs

I had first noticed Michael Frye (see his photographs

To make an already long story short, as you can see on this page of

To make an already long story short, as you can see on this page of