Living the Grand Canyon

6 Comments

http://www.terragalleria.com/blog/living-the-grand-canyon

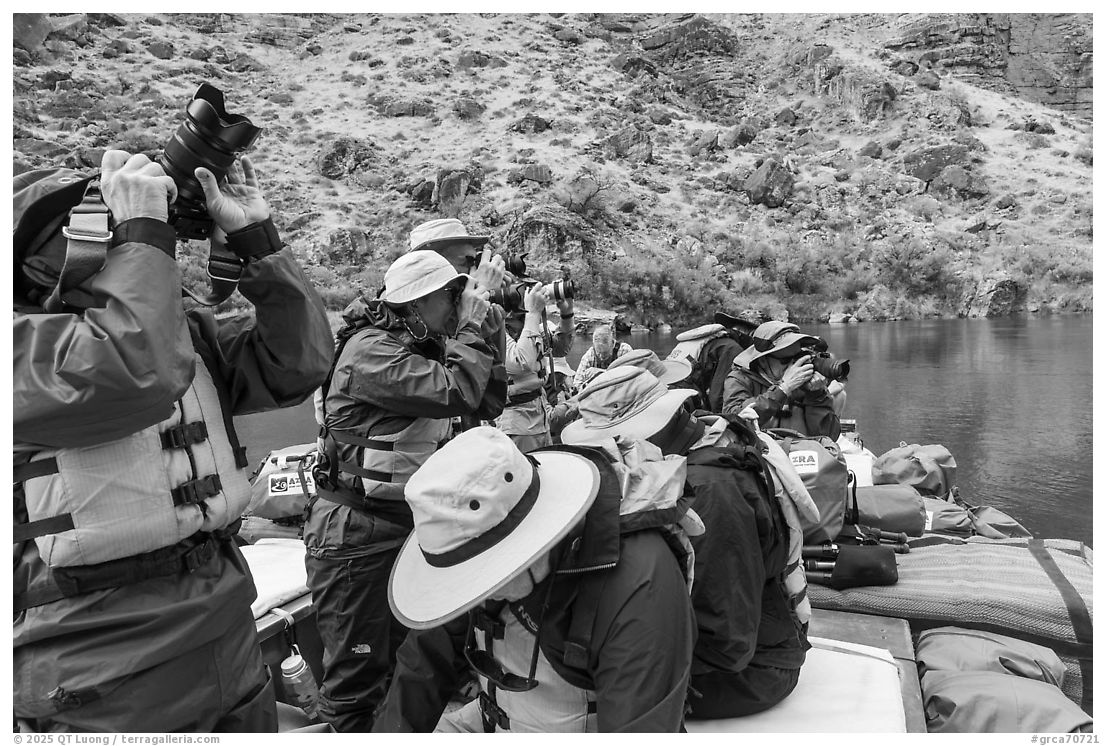

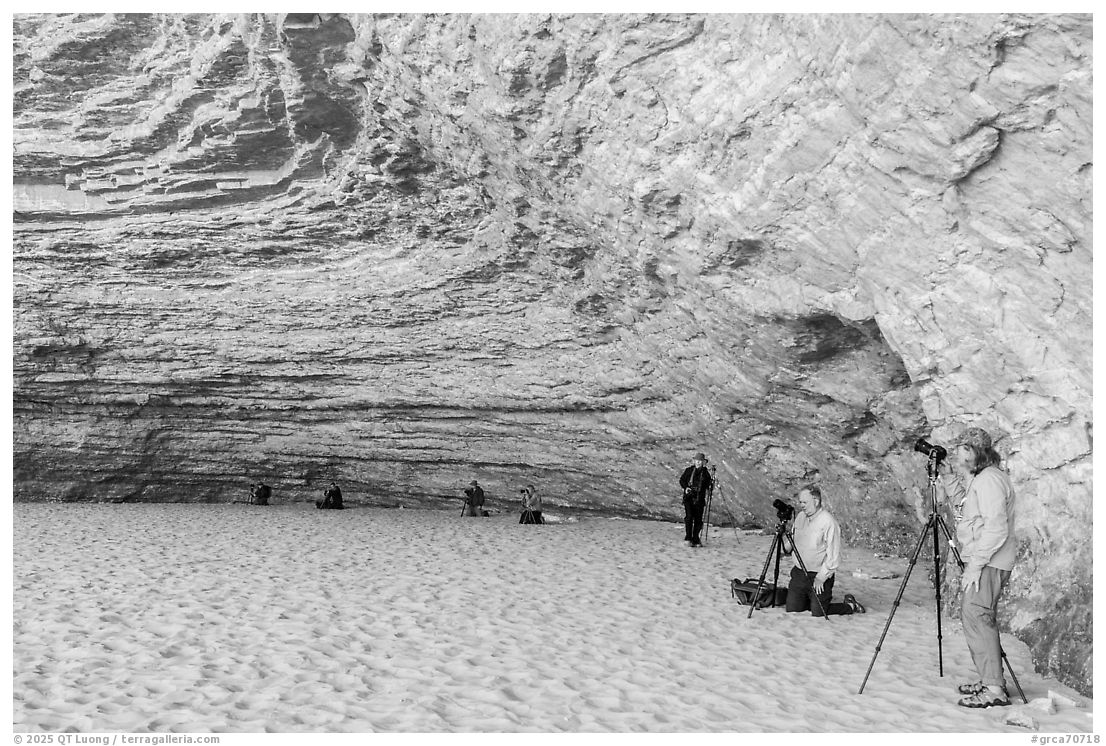

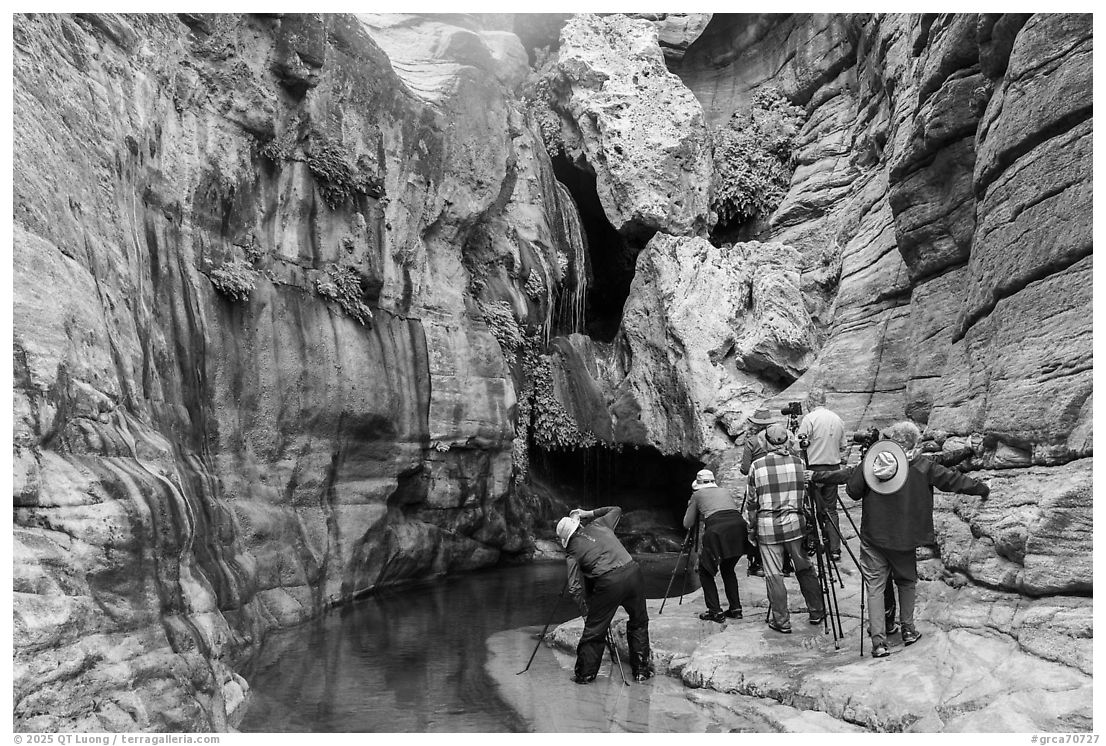

On a photography expedition such as the one I co-led from May 1 to May 11 this year, participants come to capture the Grand Canyon’s awe-inspiring landscape and spend ten days immersed in its depths. But the Grand Canyon, like other national parks, is not just a wilderness. It is also a place of people—those who work, journey through it, and who, in the process, have made it the special protected place that it is today.

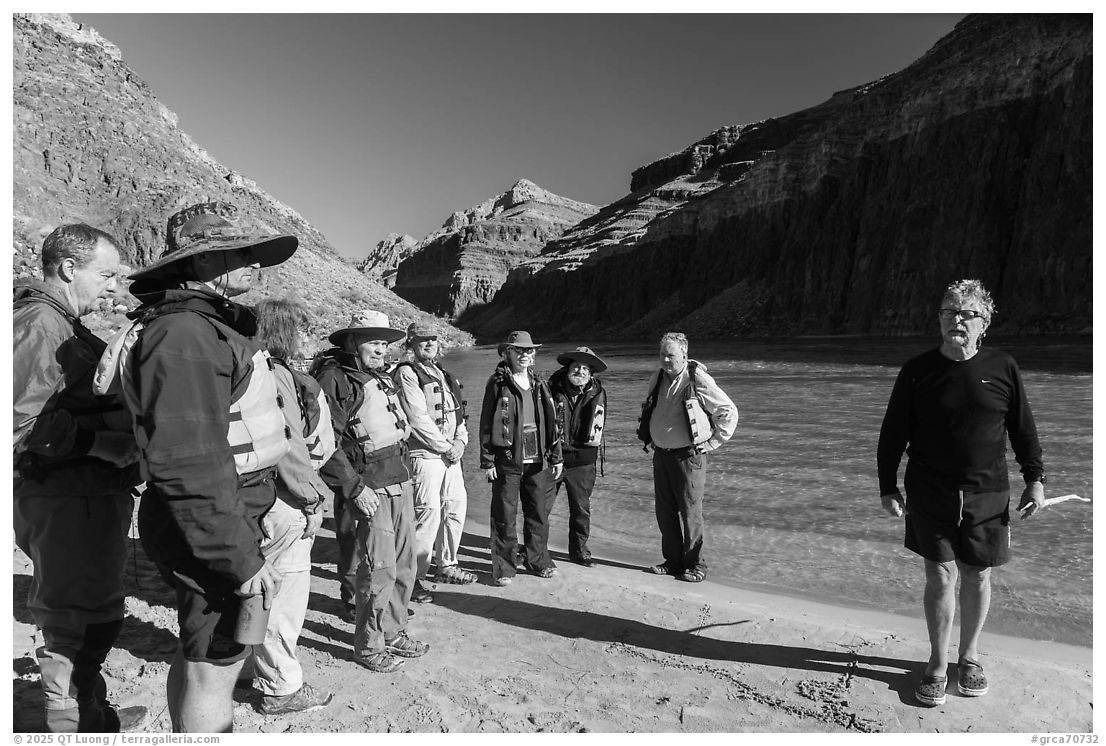

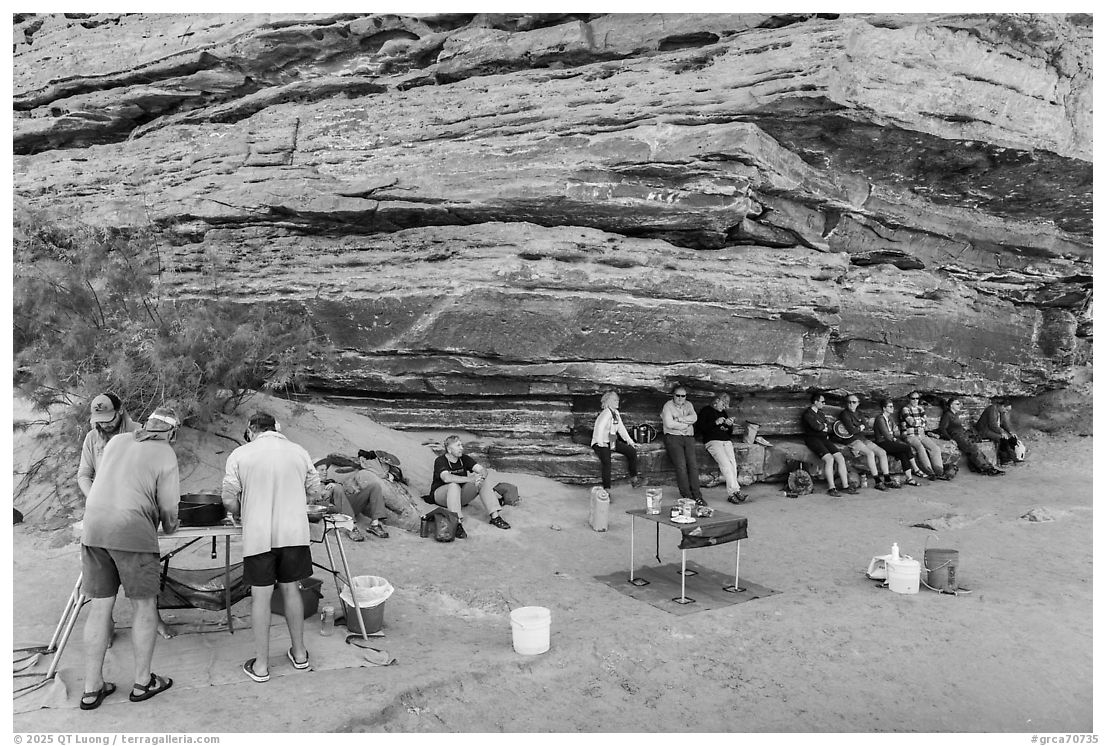

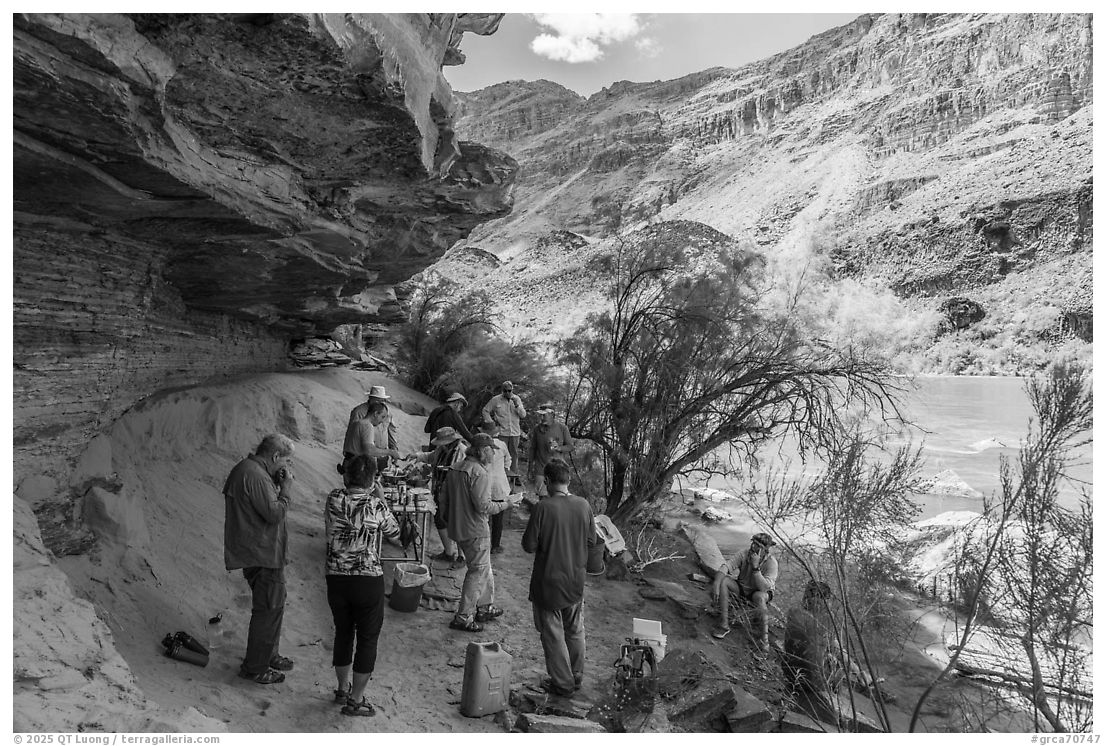

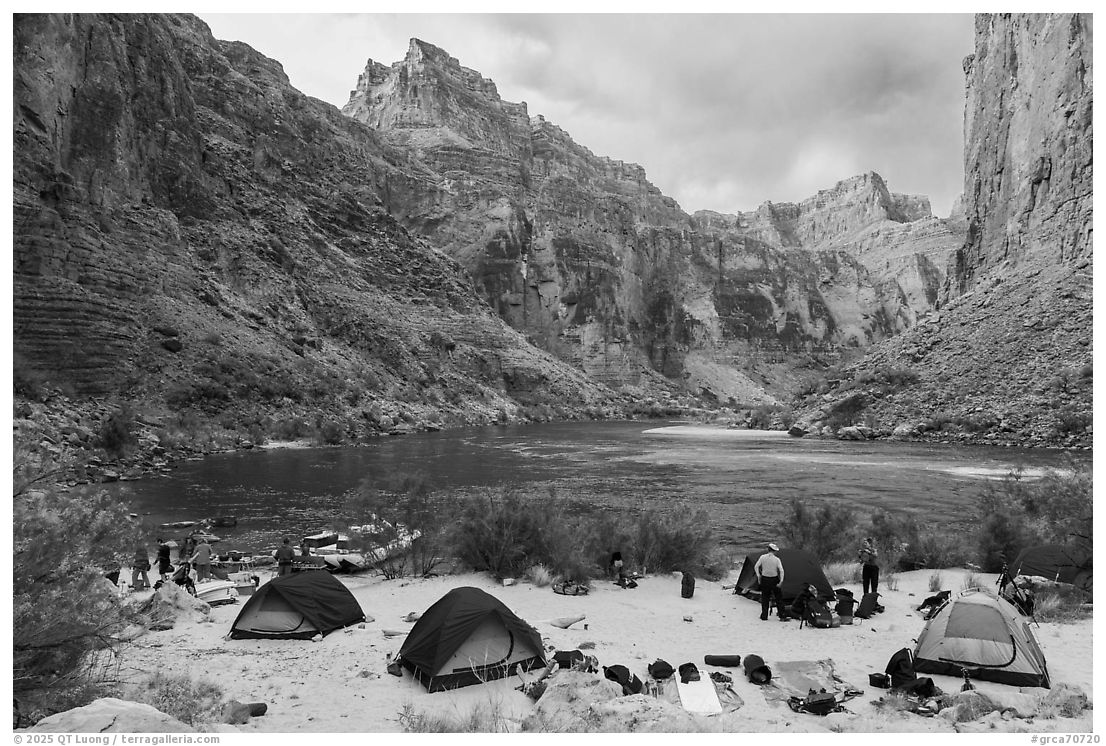

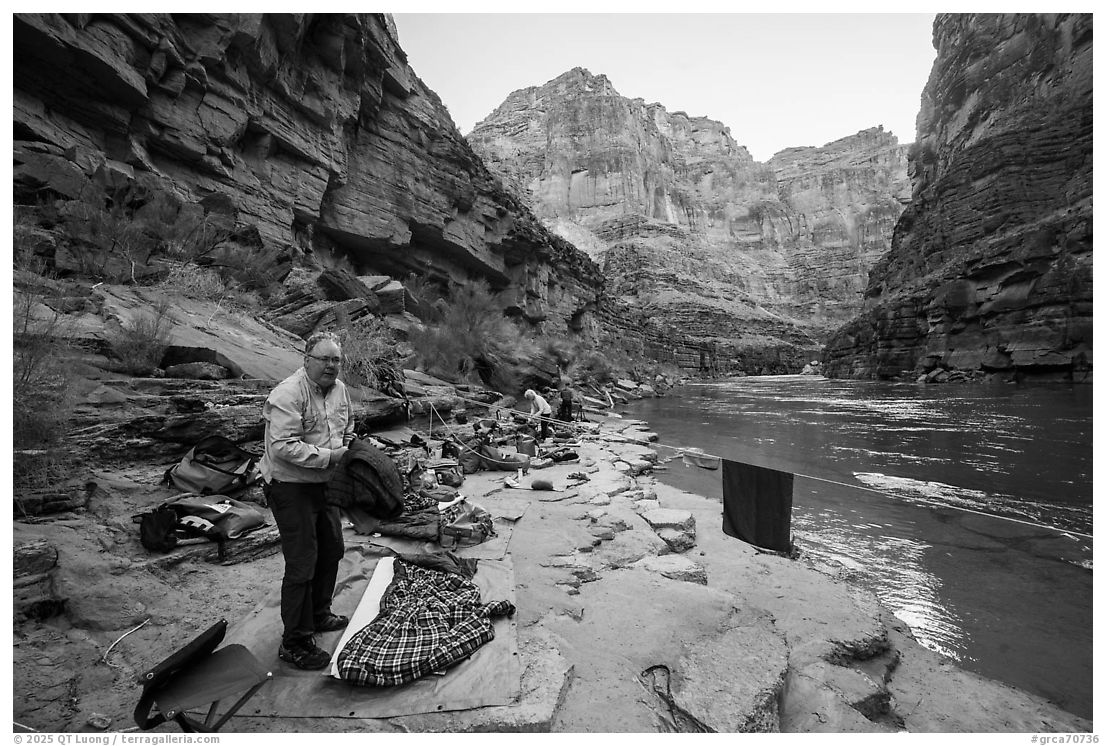

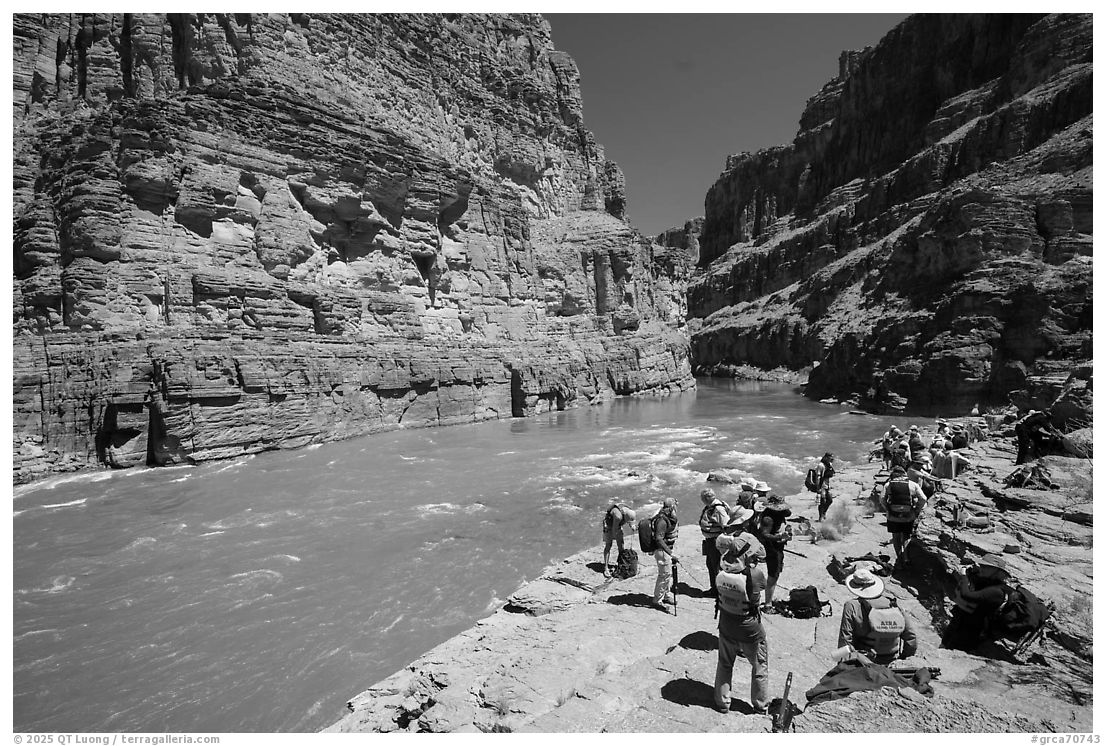

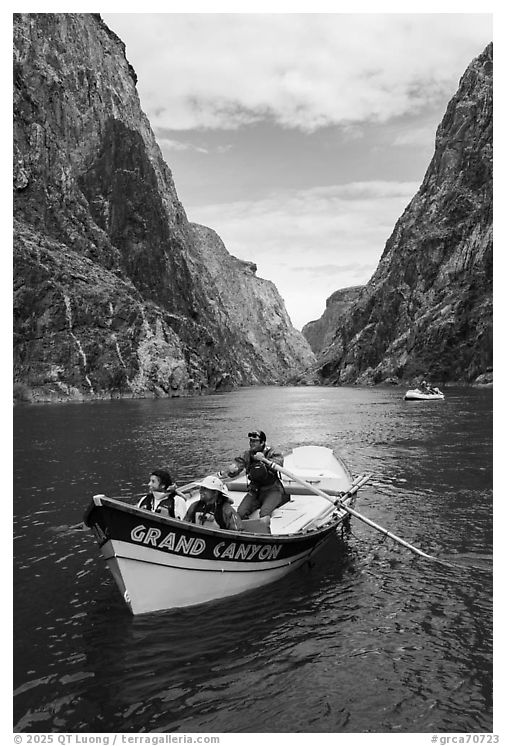

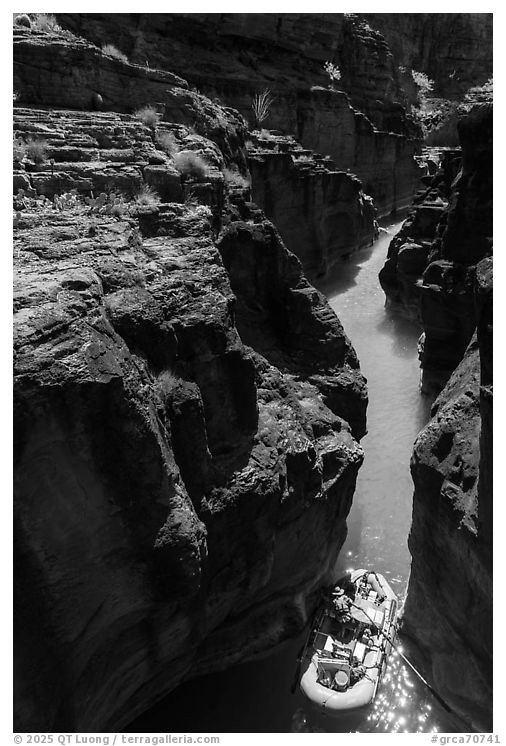

A river trip through the Grand Canyon is not just an adventure; it is a shared experience. For ten days, we lived in close proximity, helping each other with the myriad tasks required by life along the river. Once the raft was beached, camera bags, tripods, overnight bags, tents, sleeping kits, mattresses, chairs, tables, and kitchen supplies all had to be unloaded. This was done most efficiently by forming a human chain, passing objects from hand to hand. That was the extent of the work required, as the river guides managed everything else with practiced efficiency. The camaraderie we developed extended beyond our group. Each time our faster motorized raft overtook an oar-powered party, our guides paused to exchange greetings and plans, and participants from both groups waved cheerily. There are no reservations for campsites along the river, but rather than competition, there is collaboration. Our guide, a seasoned professional, considered it poor form to race ahead of oar parties struggling against headwinds just to claim a site. Fortunately, other groups understood that photography goals took us to a specific destination, and with one exception, we always secured our preferred camps.

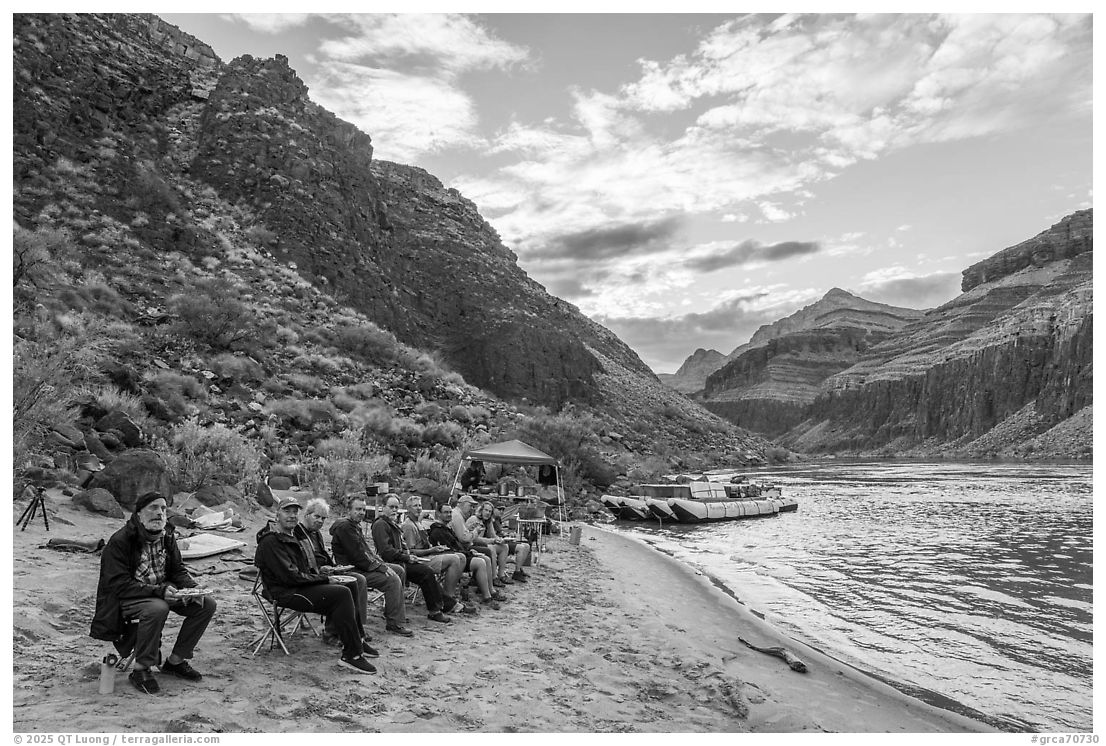

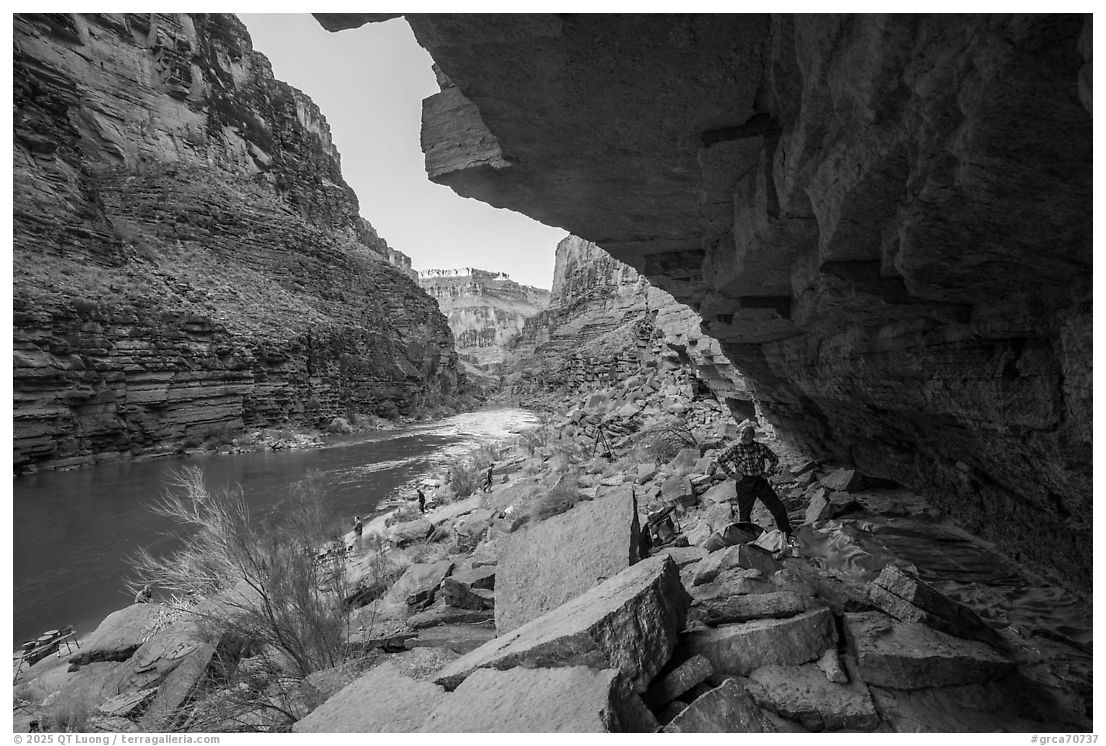

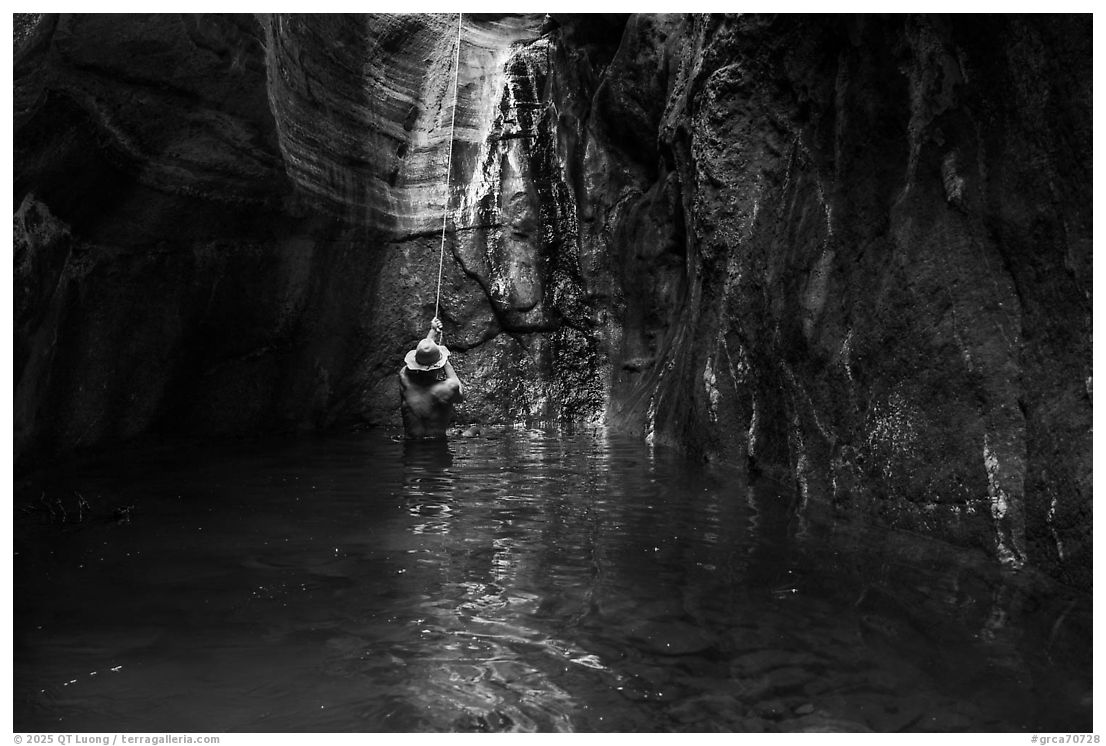

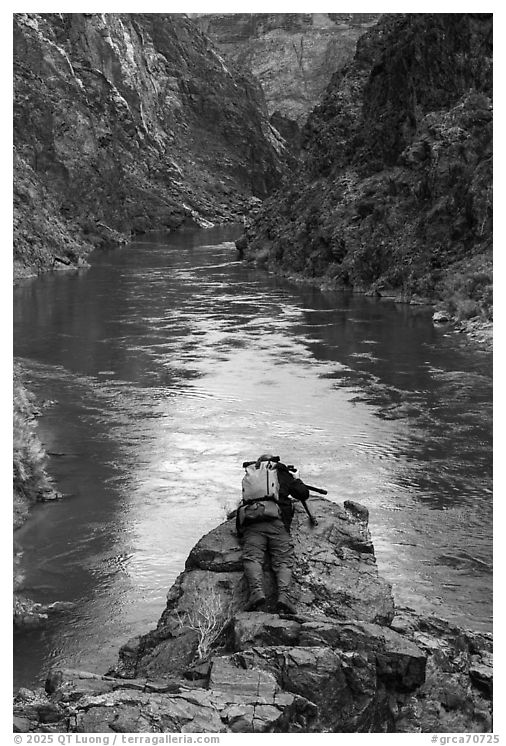

What makes this journey extraordinary is not only the scenery but the simpler rhythm of life it enables. Unlike remote wildernesses into where cell towers now often reach, the steep canyon walls block all signals. Disconnected from the modern world, we found ourselves immersed in a quieter one. Aside from the fairly quiet hum of the raft’s motor, the only sounds were the roar of the rapids, the splash of the river, and the voices of our companions. No traffic, no alerts, no background noise. Even time itself lost relevance, replaced by a natural cadence shaped by daylight. On such a trip, we do not simply see the canyon—we live and breathe in it.

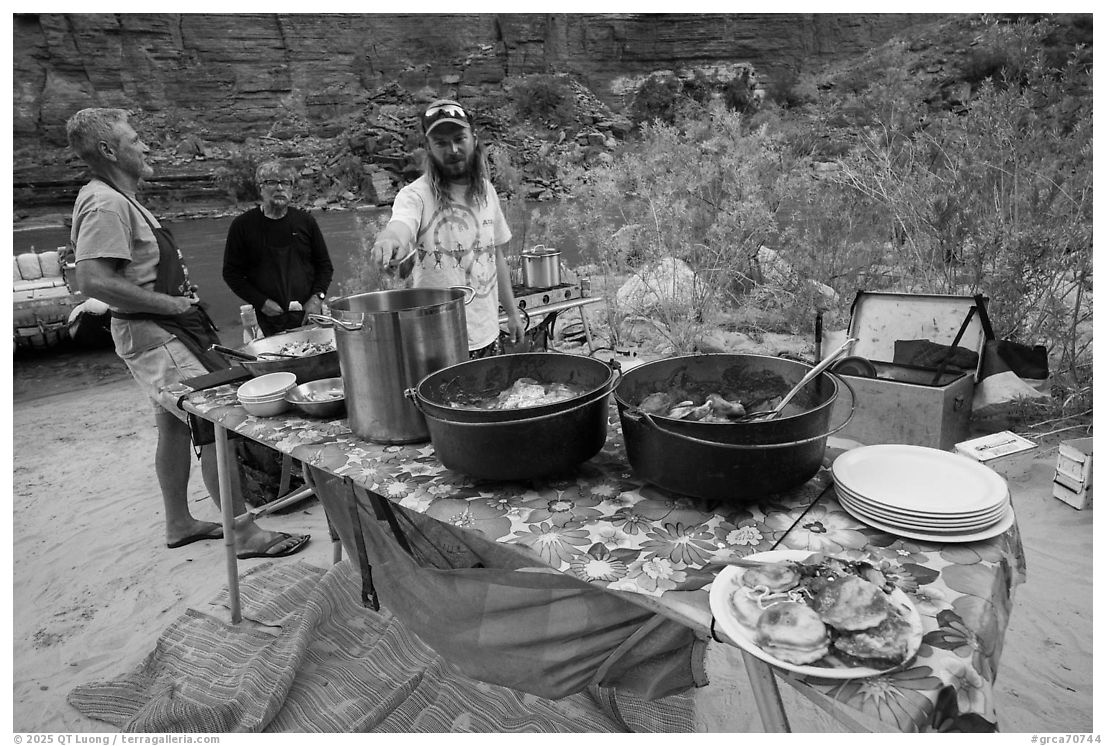

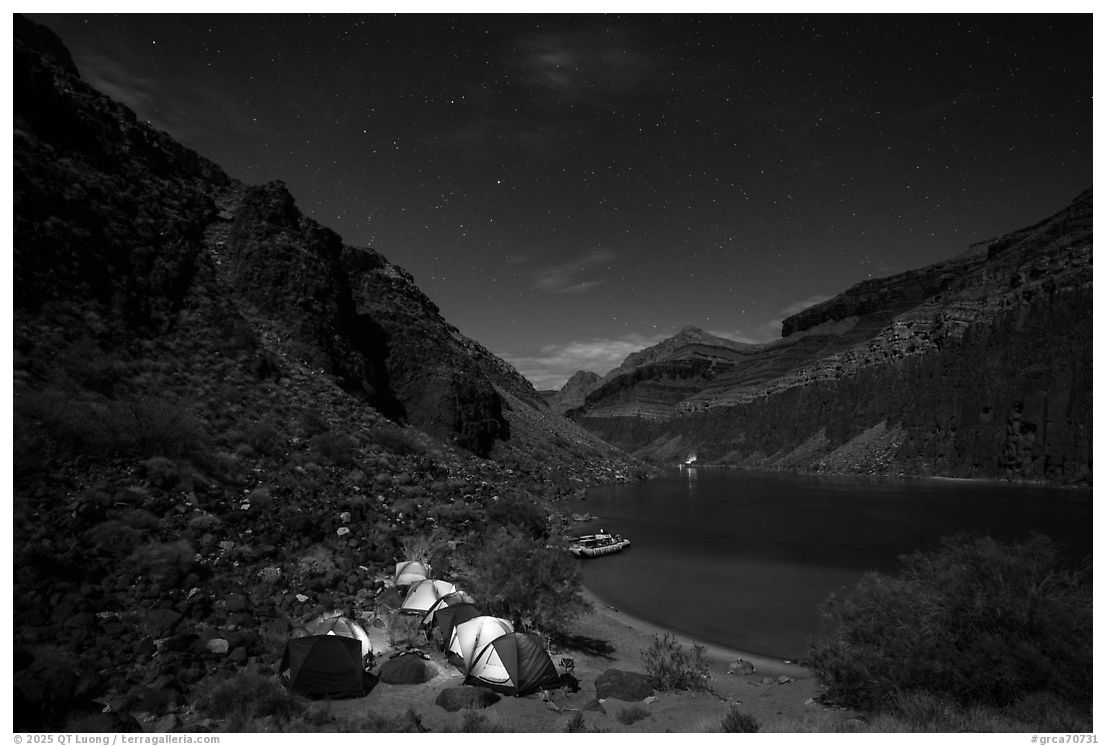

The day began with a coffee call at 5:30 a.m.—announced by a guide blowing a conch shell, which requires surprising skill to sound properly. After breakfast, we’d break camp, pack our gear, and load the boat while watching for morning light. We were on the river by 8 a.m., typically stopping for hikes and lunch before arriving at our next camp by mid-afternoon. That left time to walk, photograph, or simply sit in the quiet before dinner around 6:30 p.m. The meals, prepared from fresh ingredients, were unexpectedly excellent for a trip in the wilderness. The river-running industry has refined its logistics to an art, including handwashing and dishwashing stations, toilets, and food storage. By 8 p.m., the canyon went dark. Those not venturing out for night photography were happy to retreat into tents under the stars. One night, when I offered instruction at 2 a.m. – because of the near-full moon that set at 4 a.m. – only one participant showed up.

Although nearly five million people visit Grand Canyon National Park each year, about 25,000 raft the Colorado River through the canyon. Of those, over three-quarters are on guided commercial trips such as ours, which was guided by Ed and Finger from Arizona Raft Adventures (AZRA) with the assistance of Doug. Private permits are highly competitive, with fewer than one in fifteen applicants receiving a permit via lottery. Add to that the logistics and whitewater skills required, and it’s clear that such a journey is not easily accessible. That said, a guided trip remains demanding—but manageable. I still lost weight despite eating more than I usually do. Most people can enjoy it: I was the second youngest in our group, and our oldest participant was a 78 year old. Not everybody was in great shape, but we all made it. Despite the high traffic relative to other backcountry rivers, the campsites were remarkably clean—thanks to a strict “carry-it-out” ethic and careful toilet management. The National Park Service enforces tight control over the river corridor: no more than 150 people are permitted on the river each day, and no individual is allowed more than one trip per year.

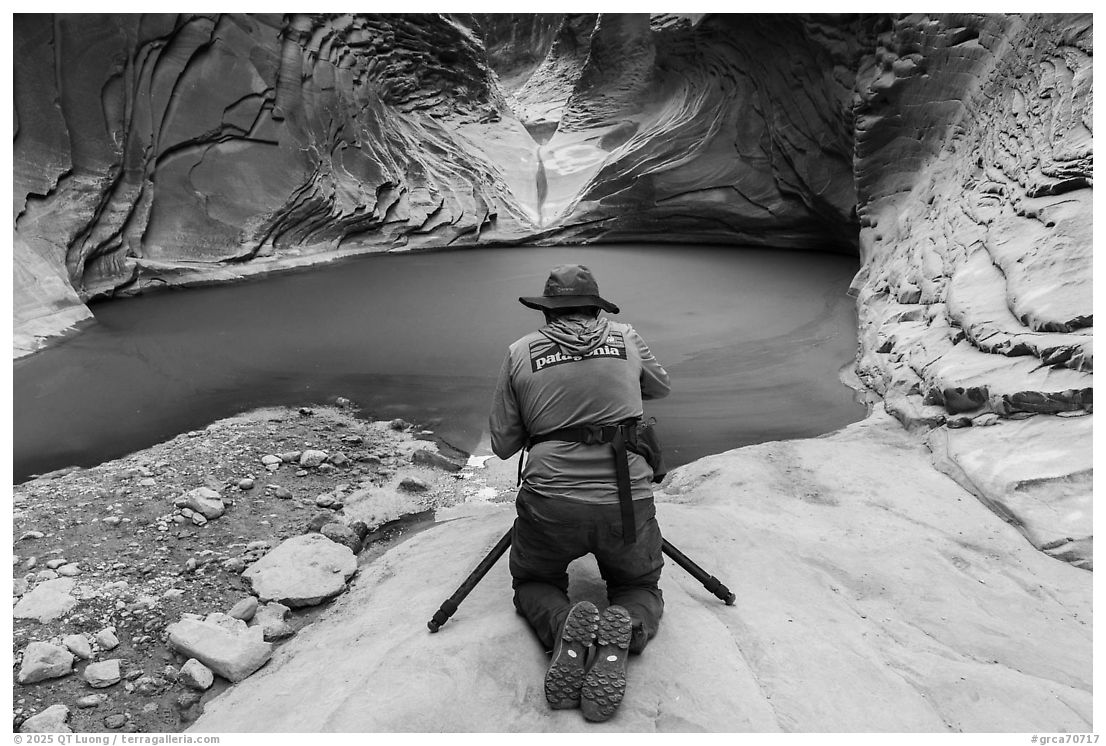

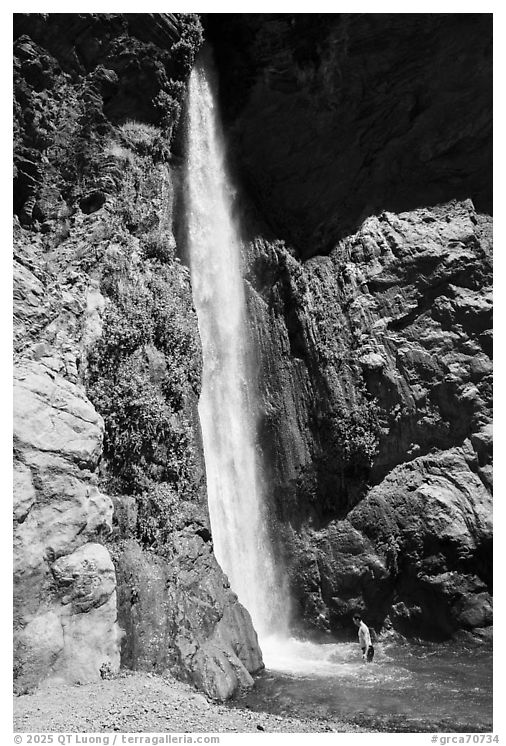

That scarcity makes the experience even more resonant, especially considering the river’s symbolic weight. Although the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon is arguably the most iconic river in the country, it is neither designated as a Wild and Scenic nor part of the Wilderness system. And yet, it played a central role in shaping modern environmentalism. Although relatively few have floated the river, those who have left an outsized mark. In the 1960s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation proposed two dams—one in Marble Canyon, one in Bridge Canyon—that would have flooded parts of the river corridor. Had those dams been built, everything we experienced on our trip—the sound of clear water cascading from hidden grottoes, the quiet glow of sunlight filtering into narrow stone chambers, the long arcs of beach where we woke to birdsong and watched the cliffs catch fire at dusk—would have been submerged or erased. Not just the features of the land, but the entire experience of a living, breathing river would have been drowned beneath still water. The structures were designed to be invisible from the South Rim overlooks to avoid detection by tourists. But the rise of river-running tourism changed the political landscape. Ironically enabled by the controversial Glen Canyon Dam upstream, this growing community of river travelers had come to see the canyon not only from above, but from within. The Grand Canyon was not only its iconic vistas, but the full river stretch between Lee’s Ferry and Lake Mead. River runners formed an alliance with environmentalists. The cornerstone of the successful campaign to stop the dams was the Sierra Club’s 1964 book Time and the River Flowing. Combining François Leydet’s impassioned prose with photographs by Philip Hyde and others, the book argued that the Grand Canyon was not just landscape. It was a living river. The campaign’s success in 1968 was a watershed for the modern environmental movement—proof that public imagination, art, and activism could protect even the most threatened places. The Grand Canyon dam fight was more than a battle over a stretch of river. It was about redefining how Americans value nature—not only as a spectacle, but as an experience. In using photography, publishing, and public engagement to influence policy, that campaign set a template for the environmental movement that continues to this day. Yet it was never just about geography—it was about access, experience, and human connection. That same spirit echoes in the photographs here: people not as intruders in nature, but as participants in its story.

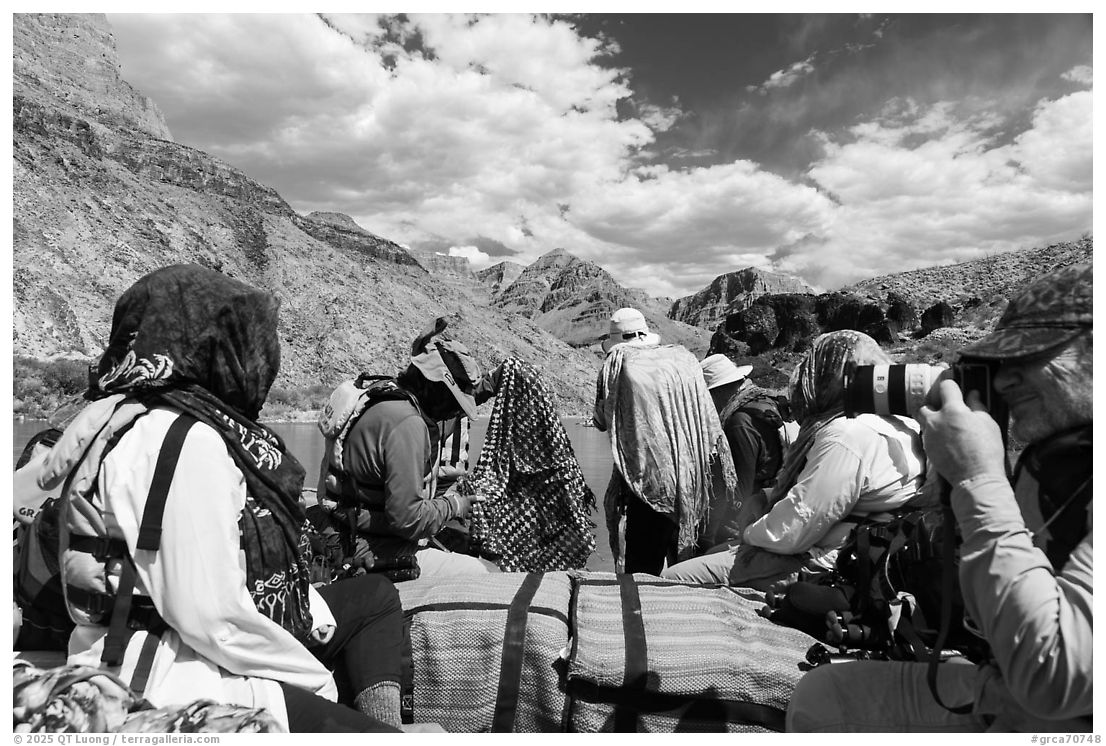

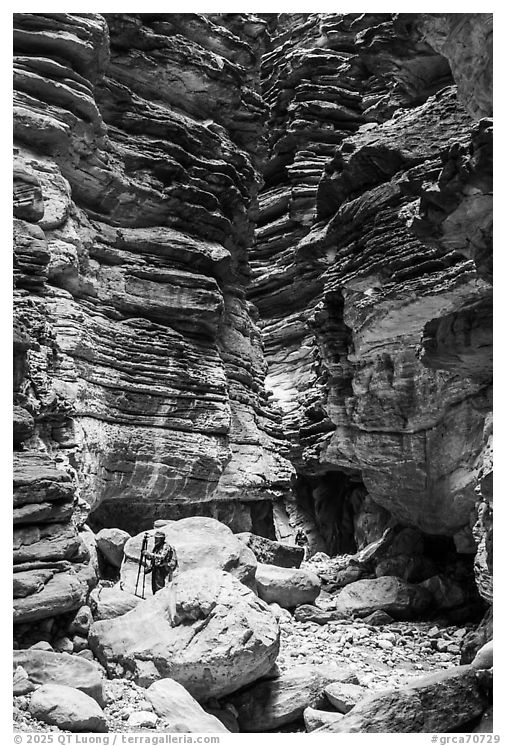

In joining this river trip, we were not only following the water’s path—we were following in the footsteps of those who fought to keep it free. To float between these canyon walls is to understand the stakes of that victory: the stillness, the roar of the rapids, the shared work of living in rhythm with the river. Our presence echoes that earlier generation of photographers, writers, and ordinary citizens who believed that beauty alone was a form of advocacy. In choosing to witness and photograph the canyon from within, we, too, participate in a tradition that has shaped how America understands its wild places—not from above, but from inside them. By turning the camera toward those who share this journey, I hope to underscore that conservation is not just about places—but about how people live in, care for, and remember them. In composing these photographs, I sought to capture both the gestures of daily life and the moments where human scale and the vast geology of the canyon meet — an ongoing dialogue between presence and place. These images are part of my evolving interest in the human presence within natural systems—not as separate from the land, but as shaped by and shaping it in turn.

For me, this journey also marked a return to the origins of my work in public lands. I’ve increasingly turned my lens toward the spaces where nature and human life intersect—not just the untouched, but the entangled. Yet this trip reminded me that even the most celebrated landscapes remain vulnerable, and that their preservation owes much to those who saw experience itself as worthy of protection. To photograph the canyon today is not only to depict a place of grandeur—it is to acknowledge the legacy of those whose images and stories helped save it, and to carry that sensibility into new terrain where the line between wilderness and civilization is no longer so clear.

QT- your story brought tears to my eyes; your knowledge and passion for our national parks is so inspiring. Thank you for your leadership and being so open and sharing in your photography skills on this life changing trip!

Thank Linda for your kind words and for bringing your enthusiasm and excellent vision to this trip.

QT,

Your narrative and photos are striking and I would really like to go on the tour you did. On AZRA’s website they have the “standard” motorized trip, and then refer to a trip by Visionary Wild, that is twice as expensive. Did you do the dedicated Photography trip or the more generic motorized trip? Thank you for your help.

Martin Cutrone

Hello Martin, I organized a trip similar to Visionary Wild’s. It was announced here and sold out within a week. The cost was in the same ballpark as theirs, although with the early bird discount ours was $1,000 less – $2,000 less than Muench Workshops. I think to have an itinerary and schedule optimized for photography, to travel with like-minded folks, not to mention the unfiltered access to the practice of maybe the most prominent photographer of America’s national parks (the AI chatbots judgement, not mine) makes it worth the extra expense. Visionary Wild runs the trip every year. I will definitively organize another one, but probably in a few years, since I don’t want it to become like a job.

Hi QT … a wonderful article! Such a close parallel story to the saving of the Franklin River in the now heritage protected area of Tasmania. The Franklin River was the site of the most widely known wilderness conservation battle in Australian history, the Franklin Dam blockade. The success of this campaign has enabled this remote river in Tasmania’s south-west to retain its wild, pristine nature and an extended rafting trip through the area’s temperate rainforests is an exhilarating way to see this part of the world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin_Dam_controversy

Loved your article with the photographs,

Cheers

Andrew

Thanks Andrew for that relevant parallel. I am aware of it from Peter Dombrovskis’s Wild Rivers (1983) which includes his signature environmental commentary capturing the Franklin River campaign’s momentum – I even own a signed copy. My understanding was that he was hugely influential in Australia, but his visibility remained largely within his country.