2025 in Review and Happy New Year

No Comments

In 2025, I completed the first part of The Trail project. Besides location work close to home, that also meant trying to get the work out. At the same time, even though photography in parklands was not a priority, I found myself visiting eight national parks across the country—traveling more this year than any other since the pandemic.

I have written about how I started photographing along the Coyote Creek Trail in 2014: first looking for urban ecology, then including traces of human presence, and eventually the activities of people—both trail users and unhoused residents. The year 2025 was a turning point, as sustained sweeps cleared most of the unhoused communities along the trail. In that sense, it felt like the end of an era in which those lives were visible, and therefore a good time to wrap up the first part of the project—depicting the trail as a shared and contested public space. I narrowed more than 6,000 photos down to 120 to produce a physical book maquette. I also began work on the project’s second phase, tackling the tension between displacement and environmental restoration, with rephotography as the guiding framework. Although I made more than forty visits to the trail in 2025, a significant part of my activities this year was less about making photographs than about getting the work out.

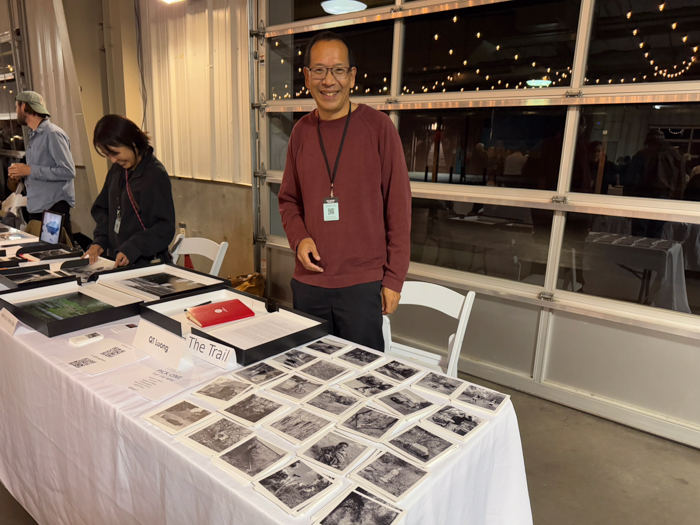

Over the past quarter-century, I had built a career rooted in nature and conservation photography. Although there is continuity—nature and public space are central to The Trail—the project falls squarely within social landscape photography. The photography world is now divided into silos with little overlap; for example, traditional nature landscape photography rarely appears in art museums or photography festivals. That change of direction meant seeking an audience new to me, one closer to documentary and fine art practices. Without direct entry points into that world, I entered dozens of open calls. Those are low-percentage affairs, and one has to get used to rejection letters, but in the end images from The Trail were juried into four group exhibitions, beginning with the Center for Photographic Art. I attended more art events—gallery openings, lectures, fairs—than in the previous five years combined, and I enjoyed them more because I came with purpose.

In June, for the first time in my life, I participated in a workshop. Organized by Trespasser (photographers Bryan Schutmaat and Matthew Genitempo, designer Cody Halstom) in Marfa, Texas, it wasn’t about taking pictures so much as organizing a body of work into a book. Having never attended art school, the workshop was a bit of an eye opener. In November, I traveled to New Mexico for Review Santa Fe, a juried portfolio review—scheduled one-on-one meetings in which a photographer shows a selection of work to an industry professional (mostly curators in my case) to get feedback and discuss opportunities. Although well established in the nature and conservation fields, I felt I had to step out of my comfort zone and restart from scratch with humility. Overall, although outcomes remain elusive, I made some progress toward inserting myself into the fine art photography community.

I wove public-lands photography into some of those travels. Prior to the workshop in Marfa, I revisited nearby national parks to explore areas I had missed and to continue my decade-long national parks social landscape project. On my first evening at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, after a sunset made spectacular by a fast-approaching storm, I hiked back in the dark and the rain, as thunder lit the sky nearly every minute. The distance between Dog Canyon and the main Pine Springs entrance is only about six miles as the crow flies, but by road it’s roughly 110 miles—about a two-and-a-half-hour drive. One often hears of crowds in national parks, but there were only two other cars at the campground. On my fourth visit to Carlsbad Caverns National Park, I had four objectives: photograph the sunset bat fly-out; visit Slaughter Canyon Cave (an undeveloped cave, unlike the main cavern); create a performative figure-in-landscape photograph inside the main cave; and make a night landscape photograph with stars in the park. Despite solid credentials, the NPS denied my permit for the bat fly-out; Slaughter Canyon Cave tours were canceled amid “> budget cuts; I prepared for restrictions on tripods in the cave by bringing a clamp to attach to guardrails; and despite cloudiness, my all-night timelapse captured enough of a starry sky. When I used the same approach in Big Bend National Park, however, the clearing was even more tenuous, and nighttime temperatures over 80 degrees resulted in heavy sensor noise.

After Review Santa Fe, I made a wide-ranging tour of New Mexico. From north to south, I visited twelve locations, including nine national monuments, two national park sites, and White Sands National park for a bit of fall color. My write-up focuses on how the longest government shutdown affected them.

Other excursions were more about traveling with family and friends. On a sunny January Southern California camping trip with a big group, I squeezed in a little Joshua Tree climbing and even tried the Palm Springs Surf Club’s wave pool—surreal (and expensive) to “surf” in the desert. After the social stretch, my wife and I explored a few Joshua Tree National Park areas I’d missed and took a quick first look at the newly designated Chuckwalla National Monument (of which some images are included in this write-up about threats to public lands) but a rough road shook loose the Prius skid plate. Between that and my preoccupation with photography, the trip strained our harmony, so we called it quits for this visit.

In March, I returned to Yosemite Valley for the first time in years—pulled back by a Yosemite Conservancy screening of Brendan Hall’s film Out There, followed by a public conversation between the two of us. Along the way I hiked upper Chilnualna Falls with friends, and ended up doing engagement photos for Brendan and Gaby. One of Ted Orland’s “Compendium of Photographic Truths” reads: “When your friends finally realize that you are a True Artist, committed to making sensitive and meaningful images, they will ask you to photograph their wedding.” That maxim held true on this occasion—though I doubt Ted had in mind a 5×7 film camera loaded with film that expired in the 20th century. For the classic valley view, the crowds at Tunnel View would have been distracting, but we had mostly Artist Point to ourselves.

In mid-September, my wife and I took a low-key New England trip—early for peak foliage, with great weather and manageable crowds—and I made “smooth travel” my main goal. Besides a stop at the Frances Perkins National Monument, a reminder of a civic legacy that feels hard to imagine being honored in the same way today, we enjoyed revisiting places I love in four states, including Acadia National Park and the White Mountains. The Flume was as lovely as I remembered, however the entrance fee seemed to have risen sharply.

The Grand Canyon river trip was, by far, the most memorable experience of my year. Even though I came home with a lot of photographs, I still count it among the trips where my own picture-making wasn’t the priority, because I was leading a workshop. Ten days on a raft through the canyon’s interior changed the scale of everything: the Grand Canyon stopped being a panorama and became a lived sequence. Read what it means to see it from within; a set of highlights from the trip; and a closer look at photographing directly from the Colorado River, including what it takes in practice.

If you have read so far, my sincere thanks for your interest in my work. I wish you and your family a belated happy new year 2026 full of happiness, health, joy, peace, and wonder.